9. Writing table

- French (Paris), ca. 1755

- By Bernard II van Risenburgh (French, after 1696–ca. 1766, master before 1730)

- White oak and fir* veneered with amaranth*, kingwood, and tulipwood; drawers of mahogany* and white oak; gilt bronze mounts; brass and iron locks; replacement leather writing surface

- H: 2 ft. 5 1/2 in., W: 3 ft. 1 7/8 in., D: 1 ft. 10 11/16 in. (74.9 × 96.2 × 57.6 cm)

- 65.DA.1

Description

This writing table set with gilt bronze mounts has an undulating top with rounded corners and is supported on four cabriole legs that are six-sided in section. It contains two locking drawers opening from the sides of the table. A writing slide that pulls out from the front is lined with green leather decorated at its edge with gilt tooling. Slides for the support of candlesticks are set above the side drawers (fig. 9-1).

Figure 9-1

Figure 9-1Each of the four corners is mounted with an arrangement of flowers, buds, and leaves below an apposed C-scroll mount, their outer edges framed with leaves whose curling bases appear as five knobs. At the lower corner of each frieze at the back and front and sides is a small mount composed of interlocking foliate scrolls. At the lower front center of the back and front is a mount composed of foliate C- and S-scrolls set with leaves and shells surrounding a curved cabochon. Pierced keyhole escutcheons are found at the center of the side drawers. These are composed of scrolls and leaves surrounding shells on a stippled ground.

The lower edge of each frieze is set with a plain gilt bronze molding that extends down the outer edge to the foot. The front surface of each leg is also set with two moldings that continue above to frame the corner mounts and extend below to the feet. Each foot exhibits a large curved concave cabochon enclosed by simple scrolls that turn to form the rounded toe of the mount. The three slides are set with simple knobs.

The curvilinear surface of the table is veneered with a broad outer band of amaranth of conforming shape. At the center is a kingwood marquetry arrangement of stylized flowers, leaves, stems, and tendrils. Surrounding this group is a large double frame of interlocking scrolls in amaranth. Above, the two scrolls support a narrow trellis of two layers, the compartments filled with veneers of quarter-cut kingwood. Below, a short curved prominence rises from the scrolls. From its top issues long kingwood twining branches carrying leaves, flowers, and tendrils that branch and pass beneath and above the sides of the frame of interlocking scrolls. Leafy twigs and tendrils extend from the hipped lower side of the frame.

The veneers covering the back and the front friezes are set within a frame of amaranth shaped to form a background for the central mount. Scrolled and twining branches of marquetry leaves and flowers in kingwood extend from either side. The ground is veneered with tulipwood. Both panels are of precisely the same size. A strip of veneer, similar to that decorating the front edge of the writing slide, is set at the top of the panel of marquetry on the back so that both the front and the back of the writing table match. Similar panels of marquetry are found on the drawer fronts at the sides of the table. The surface of the writing slide, to either side of the shaped leather panel, is veneered with rising branches of leaves, flowers, and tendrils in kingwood in a tulipwood ground (fig. 9-2). The slides extending from either side of the table are simply veneered with quarter-cut tulipwood and surrounded by a raised molding of amaranth (fig. 9-3). The left-hand drawer is fitted with compartments intended to hold writing equipment (fig. 9-4).

Figure 9-2

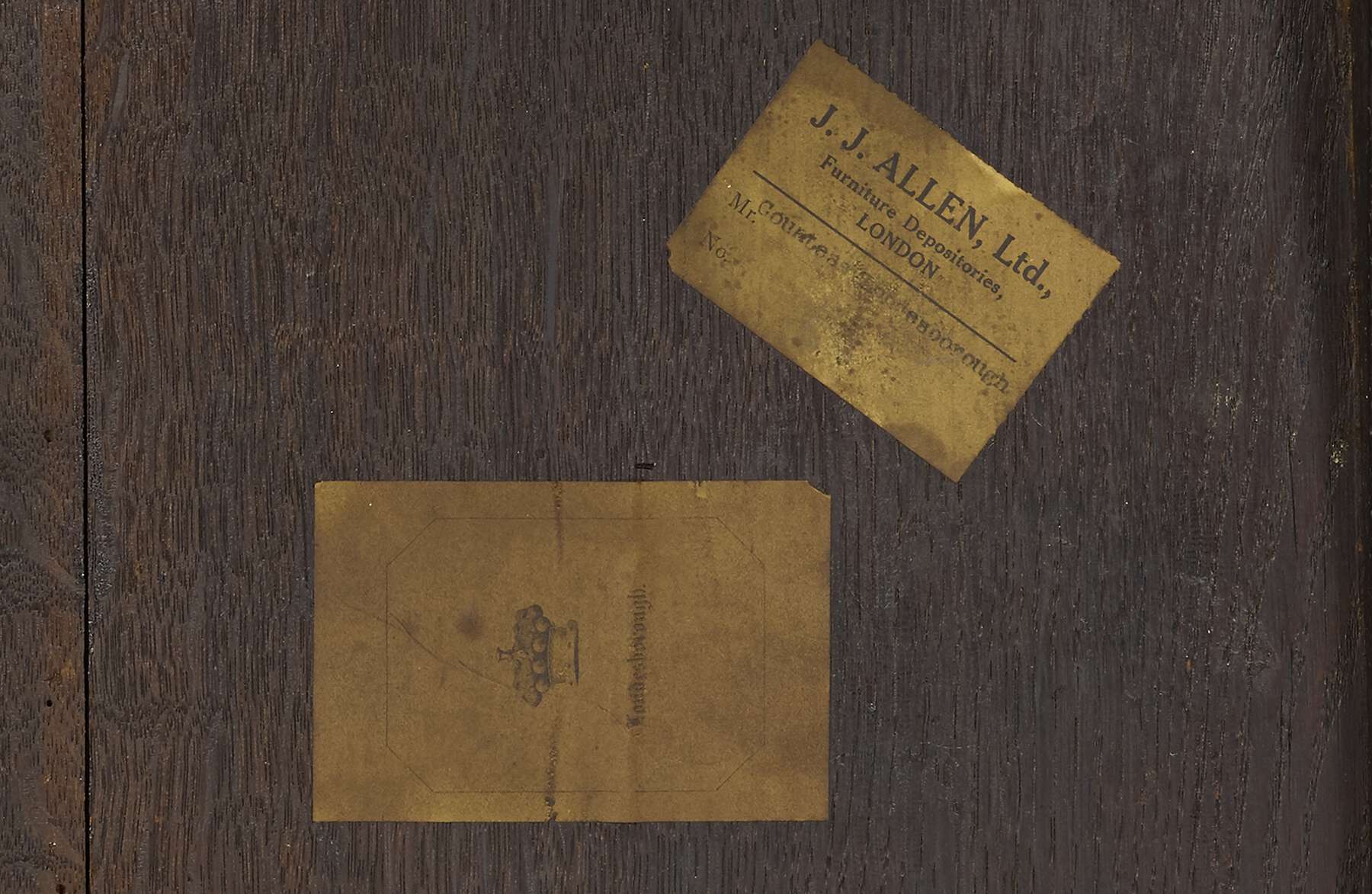

Figure 9-2Marks

The undersurface of the table, at the left front rail, is stamped “B.V.R.B.,” for Bernard II van Risenburgh, and flanked by “JME,” for jurande des menuisiers-ébénistes (fig. 9-5). Two paper labels are glued to the undersurface. One is printed “Londesborough” beneath a baron’s coronet (fig. 9-6). The other reads “J.J. ALLEN, Ltd., / Furniture Depositories, / LONDON / Mr…..COUNTESS LONDESBOROUGH / No.”

Figure 9-5

Figure 9-5 Figure 9-6

Figure 9-6Commentary

The table was made by Bernard II van Risenburgh.1 Two other tables of the same form bearing three slides and a drawer at each side and mounts of the same model exist. The example most similar to the Museum’s was that sold from the collection of Barbara Piasecka Johnson at Sotheby’s New York in 1992.2 Stamped “B.V.R.B.,” it was of precisely the same form and carried the same mounts, but the design of the end cut marquetry was markedly different. That on the top consisted of a broad frame of apposed C-scrolls centered by an arrangement of two intertwining leafy stems. The frame on the top of the Museum’s table (fig. 9-7) carries an area of trellis containing small rectangles of quarter-cut veneers with stems, leaves, and flowers dispersed across the surface of the table in a considerably looser design. The marquetry on the friezes of the Johnson table is framed with a wide border of kingwood.

The design for the marquetry on the Johnson table is also seen on one in the Wrightsman collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (fig. 9-8).3 On this table, a more luxurious item with a raised and pierced gilt bronze gallery, many of the flowers and leaves are made of mother-of-pearl and horn painted green, red, and blue. J. Paul Getty attempted to purchase this table. In the library at the Getty Research Institute a catalogue of the Parke-Bernet sale of the collection of Sarah Jones Walters in 1941 is annotated in Getty’s own hand.4 It reveals that he bid $4,000 for this table. It sold for $13,200 to Baron Cassel van Doorn.

Figure 9-8

Figure 9-8While a number of smaller tables equipped with writing slides, stamped by or attributed to this master, exist, the mounts seen on the friezes, corners, and feet of these tables are unique.5 Only the vertical floral clusters set below the C-scrolls at the corners have been used on another piece of furniture made by Van Risenburgh. They are found to either side of the fall front of the large secrétaire bibliothèque acquired from the marchand-mercier Lazare Duvaux in 1755 for the cabinet of Louis XV at the Grand Trianon (see fig. 2-6).6

Daniel Alcouffe has noted that Duvaux sold two tables of this rare type,7 one to Madame de Pompadour for use at Bellevue in 1752—“1020 [ . . . ] Une table à contours en bois d’acajou plein, avec trois tablettes qui se tirent, garnie de boutons & chaussons dorés d’or moulu, garnie de roulettes dans les pieds, 112 l.”—and another in 1754 to a Monsieur Fontferriere—“1844 [ . . . ] Une table à contours aussi plaquée en bois de rose, avec trois tablettes qui se tirent, 90 l.”8 It seems that Van Risenburgh continued to produce such tables until his retirement because of ill health in 1764. In the inventory of stock sold to his son in that year is “un bâtis d’une table de 3 pied [97 cm] des tablette et tiroir par les bous.”9

A label pasted beneath the table (see “Marks” above) is of nineteenth-century date. It is printed with a baron’s coronet and the name “Londesborough” in Gothic characters (see fig. 9-6). It could have been placed there by William Francis Henry Denison, second Earl of Londesborough (1864–1917), or his father, William Henry Forster Denison, first Earl of Londesborough (1834–1900). The table was probably acquired by Lord Albert Denison, the first Baron Londesborough (1805–1860) and the son of George IV’s last mistress, the Duchess of Coyngham. He had inherited great wealth from his maternal uncle and was an avid collector (see cat. no. 2). He was created baron in 1850, so the label would postdate that year.

In Collector’s Choice it is noted that Getty had first seen the table at the London dealer Botibol in 1937, together with the bureau plat by Van Risenburgh (see cat. no. 10): “Greatly admiring them, he [Getty] was informed that neither piece was for sale. Nothing daunted, he said, ‘I’ll make you an offer for both pieces. And I’ll hold my offer open indefinitely. If you ever decide to sell them—and at my price—just cable me to Los Angeles.’ That was during the summer of 1937. . . . It was May of 1940 when he received the cable accepting his offer.”10 However, Museum records show that in fact he acquired the table from Botibol on July 7, 1938, for $7,291.28. A letter from Botibol written on January 25, 1940, reads, “I enclose a photograph of the fine Louis Quinze writing table which I bought at Christies for L1,400 [see cat. no. 10]—also Louis Quinze inlaid table for which I wanted L3,500 [this catalogue entry].”11 This letter is therefore referring back to the 1938 sale and shows Botibol’s original asking price.

Provenance

Mid-nineteenth century–1860: possibly Albert Denison, first Baron Londesborough, English, 1805–1860, by inheritance to his son, William Henry Forester Denison, 1860;12 1860–1900: William Henry Forester Denison, second Baron and first Earl of Londesborough, English, 1834–1900, by inheritance to his son, William Francis Henry Denison, 1900; 1900–1917: William Francis Henry Denison, second Earl of Londesborough, English, 1864–1917, by inheritance to his wife, Grace Adelaide Fane Denison, 1917; 1917–33: Lady Grace Adelaide Fane Denison, English, 1860–1933 (London, England), upon her death, held in trust by the estate, 1933; 1933: Estate of Lady Grace Adelaide Fane Denison, English, 1860–1933 [Hampton and Sons, London, July 24, 1933, lot 123];13 1933–38: J. M. Botibol, in business 1920–53 (London, England), sold to J. Paul Getty, 1938;14 1938–65: J. Paul Getty, American, 1892–1976, donated to the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1965.

Bibliography

, ill. facing p. 57; , 147–48; , 118, 121, 124, fig. 9; , 149; , vol. 2, 309; , 139; , 52, 53, no. 68; , 37, no. 65; , 153, fig. 4.

- G.W.

Technical Description

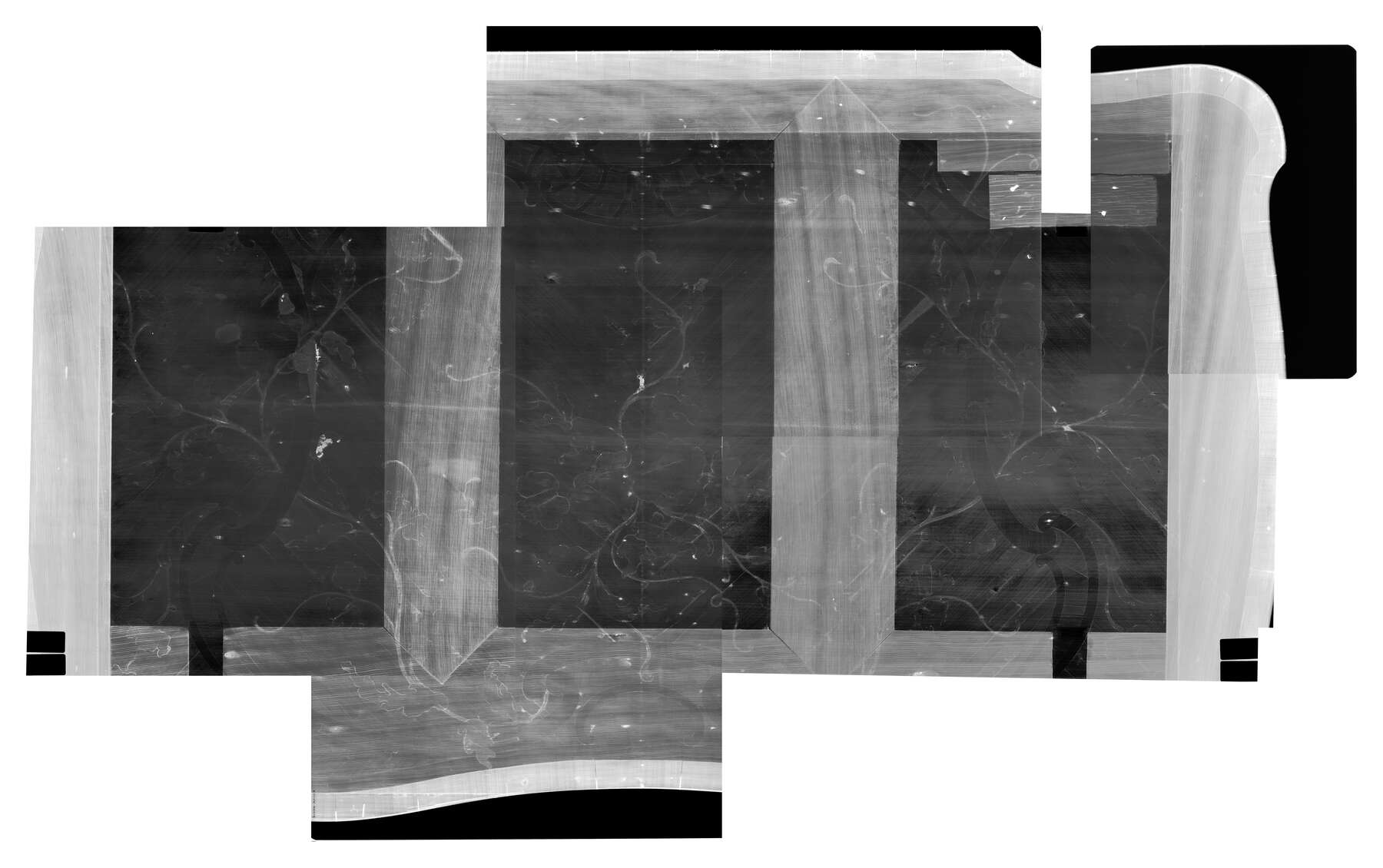

The top of the table is assembled in a very unusual manner. A cursory examination (through the drawer openings, fig. 9-9) of the underside of the top gives the impression of a tripartite frame-and-panel construction, with rails on all four sides and two equally spaced medial rails running from front to back. X-radiography of the top, however, reveals a very different construction (figs. 9-10, 9-11). The top is in fact based around an extraordinarily broad, single plank of fir approximately 81.5 cm long, 50 cm wide, and 1.4 cm thick. Along the rear and side edges, the plank is framed by 2-cm-thick oak rails, about 7 cm and 9 cm wide, respectively. These rails are grooved along their inner faces, and the fir plank is correspondingly rabbeted to form a tongue along these edges. Unusually, the rear rail is not fixed to the side rails with the customary mortise-and-tenon joins. Rather, it is simply attached with tongue-and-groove joints. The two medial “rails” are not rails in the conventional sense but are merely slats of oak, approximately 6 mm thick, that are glued to the underside of the top. The ends of the slats are pointed and fit into recesses cut into the front and rear rails. Similarly, X-radiographs show that the front “rail” of the top is also simply a 6-mm-thick slat, glued to the underside of the broad fir plank. This slat, which is approximately 12.5 mm wide at its widest point, has no mechanical joints fastening it to the side rails, the medial rails, or the fir plank itself. At either end of the front edge, where the top bows forward, additional blocks of wood approximately 2 cm wide have been glued on to extend the substrate.

Figure 9-9

Figure 9-9 Figure 9-10

Figure 9-10 Figure 9-11

Figure 9-11The edge of the tabletop has a thin quarter-round molding of solid tulipwood. This molding is made up of approximately 76 individual pieces of wood, averaging about 4 cm long, with the grain oriented perpendicular to the edge of the top (“cross-grain” molding). Although the molding appears to be only about 8 mm wide, X-radiographs clearly show that the tulipwood pieces are actually about 2.1 cm wide and extend well beneath the adjacent amaranth veneer banding (fig. 9-12).

Figure 9-12

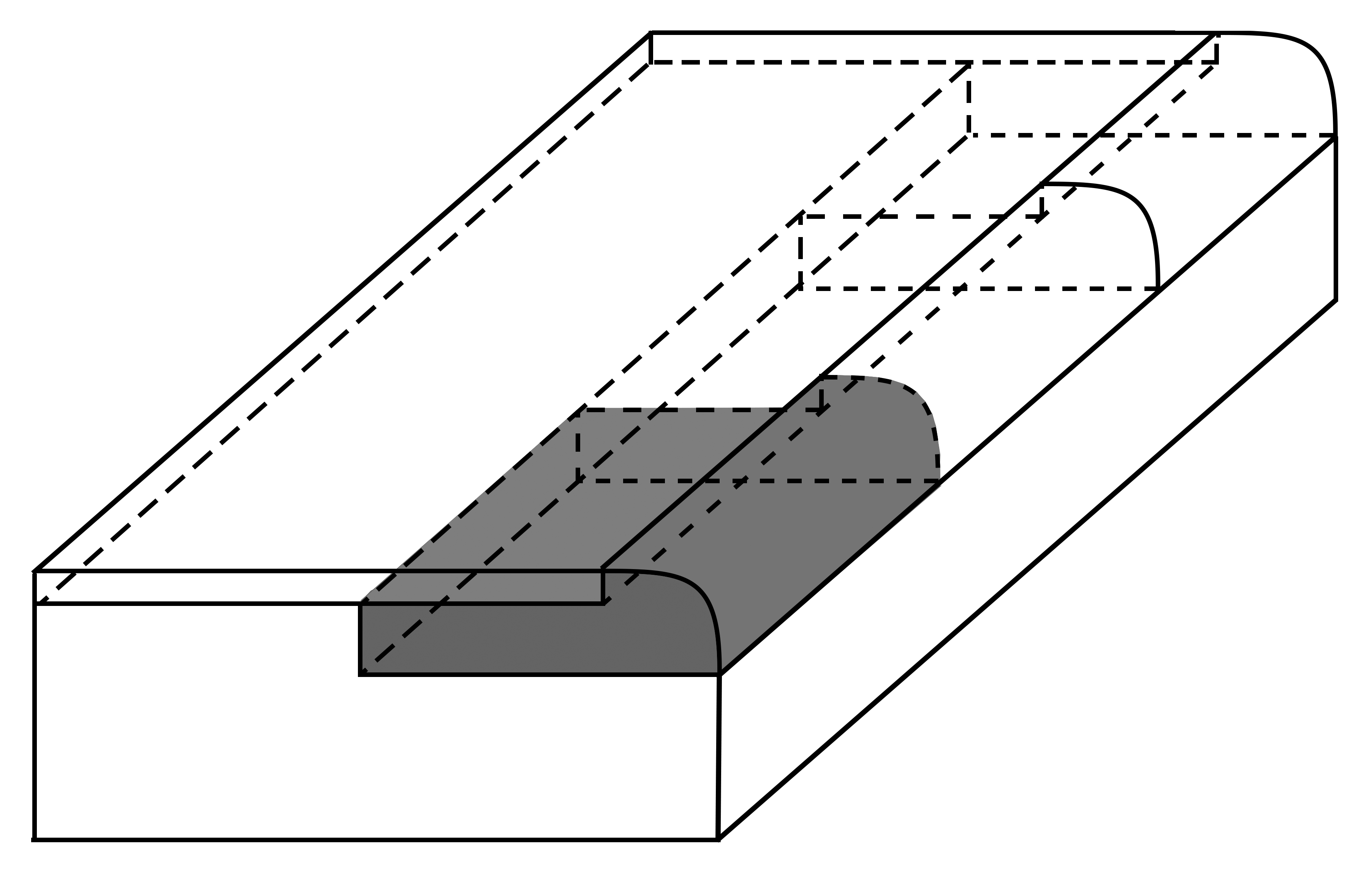

Figure 9-12The top is attached to the case with four loose butterfly tenons that slide into pairs of dovetail mortises cut into the front and rear top rails of the case and the front and rear framing rails of the top.

The case bottom is made of four butt-joined quartersawn oak boards whose grain runs front to back. Three of the boards are 25 cm wide; one is 12 cm wide. The narrow board has a noticeable strip of sapwood nearly 1 cm wide along one edge. The central wide board has a triangular piece of wood spliced into one corner; this piece measures approximately 10 x 3.5 cm and appears to be an original part of the construction (fig. 9-13).

The drawers (see fig. 9-4) are extremely similar in construction to those of Van Risenburgh’s double desk (see cat. no. 8). They are made primarily of unfigured mahogany, with the exception of the drawer fronts, which are of oak, veneered on their inner and top surfaces with mahogany. The top edges of the drawer sides and backs are gently rounded and the dovetails at the rear corners are mitered at the top. The drawer bottoms are set into rabbets on all sides and then covered with mitered strips glued around all four edges. Unlike the double desk’s drawers, the grain of the bottoms of these drawers runs from front to back.

The writing slide and candlestick support slides (see figs. 9-2, 9-3) are made in a manner analogous to the top. In all cases, broad, thin planks of fir with their grain running from side to side serve as the basis of the slides. These are fixed with thicker oak battens, or breadboard ends, on both sides, using rabbet and dado joints. At the front, a thin slat of oak is glued to the underside of the fir plank as an ersatz front rail. On the writing slide, three additional oak slats, approximately 5 cm wide, are glued to the underside of the fir plank, running from front to back, presumably to stiffen the panel. There is no rear “rail” on the writing slide. The candlestick slides each have one additional slat glued to the underside of the fir panel. These slats are approximately 8.2 cm wide and run from side to side (between the side battens) about two-thirds of the way back from the front of the panel. Stop blocks are glued to the upper surface of the slides near the rear edges that prevent them from pulling completely out of the case.

On all three slides, the fir panels have long, shallow, sliding dovetail mortises cut into the bottom surfaces, running from the rear of the panel almost to the front. On the writing slide, the three mortises are approximately 1.1 cm wide and are covered by the medial slats; thus the mortises are visible only in X-radiographs. On the candlestick slides, the mortises (one on each slide, not symmetrically placed) have been filled with cross-grain strips of fir that appear old and whose oxidized surface matches the surrounding fir panel surface. These mortises have no current function and may represent an original design alteration.

X-radiographs of the top and the proper right slide reveal a number of unexplained holes in the fir panels. These include several triangular holes on each panel, 1.5 to 3 cm deep, apparently made by handmade nails driven into the edges of the panels. In addition, on the underside of the top there is a set of at least eight round holes, approximately 3 mm in diameter, arranged in a zigzag pattern, and now filled with putty.

The presence of so many extraneous holes and dovetail mortises in the fir panels of the top and slides suggests the reuse of old wood. Unfortunately, it has not been possible to determine with certainty whether this represents the original construction by Van Risenburgh or is the result of a later alteration, though one interesting piece of evidence points to the former. The similar table at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (see fig. 9-8), also has its top made from a single broad fir board, and, remarkably, this top has two long transverse sliding dovetail mortises, nearly identical to those on the Museum’s slides. The Metropolitan panel appears to have been thinned somewhat so that the mortises are shallower, but in all other respects, these mortises appear identical to those on the Museum’s table. As the two tables have no known shared history of restoration, this suggests that a very large plank of fir was, in fact, recovered from some previous construction and reused in Van Risenburgh’s workshop for the fabrication of both these tables.15

The unusual construction of the top and slides has no analogue in other works by Van Risenburgh in the Museum’s collection. The most similar sliding panels by Van Risenburgh are on the display cabinets (see cat. no. 2); however, the display cabinets’ slides are made using full-thickness oak boards in the main panel rather than thinned fir planks. The Metropolitan table has slides constructed of oak, more similar to the display cabinets than to the Museum’s table.

Based on evidence revealed by examination of the marquetry decoration, X-ray analysis, and tool marks present on the table, it is likely that the majority of the marquetry was cut using a fretsaw, with some areas inlaid. The stylized flowers and leaves are made of single pieces of so-called oyster veneer (cut at an oblique angle to the grain direction of the timber), while the branches are made of numerous quartersawn veneer pieces lined up, end to end. In several places there are clearly visible connecting cuts between separate kingwood elements (fig. 9-14). Along with the rounded tips of the leaves, these are a strong indication that the majority of the marquetry was created using a fretsaw. As with the double desk by Van Risenburgh (see cat. no. 8), the overall high quality of the fitting of the kingwood elements into the tulipwood background suggests that the cutting was done using bevel or conic cutting, resulting in nearly flawless seams.

Figure 9-14

Figure 9-14X-ray examination of the marquetry also revealed numerous small holes that had been caused by the placement of veneer pins during construction. These small iron nails were placed alongside a piece of veneer to stop it from sliding out of position during gluing and clamping. These holes are now only visible in X-ray, and, as is symptomatic of hand-forged tacks predating the Industrial Revolution, they are of rectangular shape.

Based on the position of the veneer pins, it is apparent that the marquetry of the top was conceived as three small marquetry compositions set one after the other within the amaranth framing. While each individual panel was primarily fabricated using conic cutting, the small kingwood elements that connect the separate marquetry areas of the top, as well as some kingwood stems, were subsequently added by inlaying using a shoulder knife, and several shoulder knife marks can be seen in these areas (fig. 9-15). Mixing techniques is typical of an accomplished marquetry workshop.

Figure 9-15

Figure 9-15Bevel marquetry cutting had almost certainly just been developed at the time of the manufacture of this table.16 The relatively small size of the individual marquetry compositions produced by conic cutting is symptomatic of eighteenth-century technical limitations; specifically, until the development of larger mechanized marquetry saws, the size of the unit to be cut was limited by the depth of the throat of the fretsaw being used.

The leather writing surface (see fig. 9-2) is almost certainly a replacement. It is rather poorly fitted to the surrounding veneer, and the quality of the tooling is not high.

Most of the gilt bronze mounts on the desk are of only moderate quality. Upon close examination, the chasing of the surfaces is rather perfunctory, often appearing to employ only a single chasing tool. The burnished areas often retain a streaky texture, and numerous small casting flaws and porosities remain visible on many mounts. The only exceptions to this rule are the escutcheons on the drawers, which are much more carefully executed. Here the chasing is precise (using at least three distinct tools to produce a variety of textures), the burnished passages have been carefully polished, and no casting flaws are in evidence.

Eight gilt bronze mounts were removed from the table for examination and analysis, including at least one example of each mount type with the exception of the chutes, or foot mounts, and the thin beaded edge molding. The mounts were analyzed by X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) to determine alloy composition. The alloys of six of the eight mounts are typical in all respects of eighteenth-century castings. The alloys of these mounts are also reasonably consistent within the group, with 18–24% zinc, 0.5–1.5% tin, 1–2% lead, and significant levels of unintentional impurities such as silver, iron, antimony, and arsenic. The two exceptions are two small scrolling acanthus mounts that appear to be poor-quality copies of other original mounts on the table. They apparently have had no chasing, and their surfaces appear ill defined, with abundant casting flaws (fig. 9-16). In addition, they were found to have levels of silver, antimony, and iron that are so low as to make it extremely unlikely that they are of eighteenth-century origin. There are a total of eight of this type of mount on the tables (two on each of the four sides; mirror images of each other). Two examples of chased versions of this mount were also analyzed; their alloys appear typical in all respects of eighteenth-century castings, suggesting that they are original.

Figure 9-16

Figure 9-16The floral corner mounts on this table have been applied in the same manner as they appear on the Johnson table (see “Commentary” above); however, they are inverted when compared to the nearly identical mounts of the Metropolitan table. An examination of the verso of the Getty mounts makes it clear that their current orientation is original. The mounts have been carefully filed to conform to the beaded moldings of the legs; because these moldings are not parallel but rather slowly converge toward the feet, the corner mounts cannot be simply inverted and reattached.

Both of the drawer locks have clearly been replaced, as evidenced by two complete sets of screw holes in the lock mortises. While the current double-throw locks appear to be handmade, the alloy of one brass lock plate was found by XRF to have low levels of most impurities but elevated levels of nickel, a combination that is very rare until the late nineteenth century. The gilt bronze pulls on the three slides also appear to have been replaced; all three have lathe-cut threaded screw shafts that have true gimlet points, which were not patented until the mid-nineteenth century.

The table was heavily restored in London by H. J. Hatfield & Sons Ltd. in 1972. According to their report, at that time the joints between the legs and the front and rear rails were disassembled, cleaned, and reglued; missing veneer around these joints was replaced. The veneer on all four legs was entirely lifted and relaid. After removing the veneer, one of the legs was found to have been previously broken and badly repaired; therefore this leg was “reset.” Recent radiography reveals that this repair was done to the right rear leg and that two sizable wood screws were used to secure the leg. As marquetry on the top was blistering and delaminating over large areas, Hatfield’s lifted and relaid virtually all the veneer, with the exception of areas that were deemed too thin and fragile as the result of excessive scraping during previous restorations. Several small missing pieces of the marquetry were replaced during this restoration; these are detectable when the table is viewed under ultraviolet illumination. The lifting and re-laying of the veneer on the top probably accounts for the relatively poor fitting of the marquetry elements in certain areas (see fig. 9-14).

- A.H.,

- Y.C.

Notes

For information on Bernard II van Risenburgh, see primarily , 183–99; , 56–63. See also Daniel Alcouffe, in , 323–24. ↩︎

Sotheby’s, Important French and Continental Furniture, Decorations, Ceramics, and Carpets, May 21, 1992 (New York: Sotheby’s, 1992), lot 84 (H: 2 ft. 6 in., W: 3 ft. 2 1/4 in., D: 1 ft. 10 1/2 in.; 76.2 x 97.2 x 57.2 cm). It had been sold previously from the collection of Paul Dutasta: Galerie Georges Petit, Objets d’art et de bel ameublement du XVIIIe siècle [. . . ] de M. Paul Dutasta, June 3–4, 1926 (Paris: Galerie Georges Petit, 1926), lot 144. ↩︎

Acc. no. 1976.155.100. , vol. 2, 306–9, no. 151. ↩︎

Parke-Bernet Galleries, The Mrs. Henry Walters Art Collection, May 3, 1941 (New York: Parke-Bernet Galleries, 1941), lot 1420; J. Paul Getty also wrote about the auction in his diary: J. Paul Getty Diary, August 8, 1940–December 26, 1941, May 3, 1941, 136–37, Getty Research Institute, IA40009, http://hdl.handle.net/10020/cifaia40009. ↩︎

For example, the dimensions of a table stamped “B.V.R.B.” and owned by Paul Dutasta were recorded as “H. 66, W. 76, D. 45 1/2 cm.” See Galerie Georges Petit, Objets d’art et de bel ameublement du XVIIIe siècle [ . . . ] de M. Paul Dutasta, June 3–4, 1926 (Paris: Galerie Georges Petit, 1926), lot 146. Watson also reproduced two tables no longer in the Wrightsman Collection, one stamped “B.V.R.B.” (H: 2 ft. 3 1/4 in., W: 2 ft. 4 1/2 in., D: 1 ft. 4 1/2 in.; 69.2 x 72.4 x 41.9 cm) and another attributed to him (H: 2 ft. 3 3/4 in., W: 2 ft. 6 1/4 in., D: 1 ft. 6 1/2 in.; 70.5 x 76.8 x 47 cm). See , vol. 2, 310–11, no. 152; and 315, no. 154; A fourth table sold at Palais Galliera, Tableaux anciens, objets d’art et de très bel ameublement [ . . . ], June 12, 1973 (Paris: Palais Galliera, 1973), lot 106, stamped “B.V.R.B.” (H: 66.5 cm, W: 46 cm, D: 32 cm). It is now at the musée de Tessé in Le Mans. ↩︎

Musée de Tessé, Le Mans, acc. no. 1906.29.66. , 198, fig. 190; , 158–59, no. 42 (G. Mabille). ↩︎

Research of Daniel Alcouffe in the files of the Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. Unfortunately, these two tables cannot be identified among those preserved today. ↩︎

, 112, 210. ↩︎

Paris, Archives nationales de France, Minutier central, XXVIII, 389, October 18, 1764, sale of the shop’s assets and its sublease, Bernard II van Risenburgh and his wife to their son. As indicated in a manuscript by Daniel Alcouffe in the files of the Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. The archival location of the probate inventory is published in , 323–24. ↩︎

, 148. ↩︎

J. Paul Getty Papers, 1909–89: Art collecting and collections, 1934–74, 1977, 1982, undated: J. M. Botibol 1939–40, in the files of the Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

Label on the undersurface of the table is printed “Londesborough” beneath the coronet of a baron. ↩︎

Correspondence with Francis Buckland, May 1984, in the files of the Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

J. Paul Getty Papers, 1909–89: Art collecting and collections, 1934–74, 1977, 1982, undated: J. M. Botibol 1939–40, in the files of the Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

The authors would like to express their appreciation to Mecka Baumeister and Danielle Kisluk-Grosheide for allowing close examination of the Metropolitan Museum’s table. ↩︎

. ↩︎

Bibliography

- 18th Century: Birth of Design 2014

- 18th Century: Birth of Design: Furniture Masterpieces 1650–1790. Exh. cat. Paris: Éditions Faton, 2014.

- Alcouffe 1974

- Alcouffe, Daniel. “Hôtel de la Monnaie, Louis XV: Un moment de perfection de l’art français.” La Revue du Louvre et des Musées de France 24, no. 6 (1974): 457–67.

- Baroli 1957

- Baroli, Jean-Pierre. “Le mystérieux B.V.R.B. enfin identifié.” Connaissance des Arts 61 (March 1957): 56–63.

- Bremer-David et al. 1993

- Bremer-David, Charissa, et al. Decorative Arts: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue of the Collections of the J. Paul Getty Museum. Malibu, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1993.

- Chastang 2012

- Chastang, Yannick. Paintings in Wood: French Marquetry Furniture. Rev. ed. London: Paul Holberton, 2012.

- Duvaux 1873

- Duvaux, Lazare. Livre-journal de Lazare Duvaux, Marchand-Bijoutier ordinaire du Roy 1748–1758, vol. 2. Edited by Louis Courajod. Paris: Lahure, 1873.

- Getty and Le Vane 1955

- Getty, J. Paul, and Ethel Le Vane. Collector’s Choice: The Chronicle of an Artistic Odyssey through Europe. London: W. H. Allen, 1955.

- Getty 1949

- Getty, J. Paul. Europe in the Eighteenth Century. Chicago: Lakeside Press, 1949.

- Getty 1965

- Getty, J. Paul. The Joys of Collecting. New York: Hawthorn Books, 1965.

- Heginbotham 2013

- Heginbotham, Arlen. “Bronzes Dorés: A Technical Approach to Examination and Authentication of French Gilt Bronze.” In French Bronze Sculpture: Materials and Techniques 16th–18th Century, edited by David Bourgarit, Jane Bassett, Francesca Bewer, Geneviève Bresc-Bautier, Philippe Malgouyres, and Guilhem Scherf, 150–65. London: Archetype, 2013.

- Kjellberg 1989

- Kjellberg, Pierre. Le mobilier français du XVIIIe siècle: Dictionnaire des ébénistes et des menuisiers. Paris: Éditions de l’Amateur, 1989.

- Louis XV . . . 1974

- Louis XV, un moment de perfection de l’art français. Exh. cat. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1974.

- Pradère 1989a

- Pradère, Alexandre. French Furniture Makers: The Art of the Ébéniste from Louis XIV to the Revolution. Malibu, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1989.

- Watson 1966

- Watson, Francis John Bagott. The Wrightsman Collection. 5 vols. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1966.

- Wescher 1955

- Wescher, Paul. “French Furniture of the Eighteenth Century in the J. Paul Getty Museum.” Art Quarterly 18, no. 2 (Summer 1955): 115–35.

- Wilson and Hess 2001

- Wilson, Gillian, and Catherine Hess. Summary Catalogue of European Decorative Arts in the J. Paul Getty Museum. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2001.