8. Double desk

- French (Paris), mid-1750s

- By Bernard II van Risenburgh (French, after 1696–ca. 1766, master before 1730)

- White oak* veneered with tulipwood*, kingwood*, and bloodwood*; drawers of mahogany*; gilt bronze mounts; gilt bronze and iron hardware and locks; stained leather

- H: 3 ft. 6 1/2 in., W: 5 ft. 2 1/2 in., D: 2 ft. 9 3/8 in. (107.8 × 158.7 × 84.7 cm)

- 70.DA.87

Description

This double-sided writing desk has two fall fronts and bombé sides and is supported by tall cabriole legs of five-sided cross section (fig. 8-1). The body of the desk is set with six drawers, with three on either side. Behind each fall front there are nine pigeonholes above four drawers (fig. 8-2).

The desk is set with elaborate, highly burnished, and chased gilt bronze mounts. A molding with a concave center frames the rectangular top (fig. 8-3). It is set at each corner with a mount composed of a central concave, stippled cabochon with elongated grooves, surrounded by a C-scroll and a long twining acanthus leaf, and above a lobed scroll and widely splaying leaf. Below are two lobed C-scrolls nested together and framed with leaves and combed flame work. At the center of each long side, clasping the concave molding, is a mount composed of a fan of five lobes on a stippled ground, topped by S- and double C-scrolls, above scrolling leaves, all supported by a short branch bearing leaves that extends to either side.

At the corners of the desk, level with the drawers, are large mounts. The central pierced area of each is surrounded by C- and S-scrolls enclosing an undulating branch bearing leaves, a flower, and buds. Above, a grooved cabochon is flanked by C-scrolls, all topped by an acanthus leaf and two leafy buds. The corner mount below ends in a cabochon surrounded by four short leaves.

A plain double molding runs between this large mount, the one above it, and down the outer edge of the leg to the foot. The sabot is composed of a double leafy scroll, the leaves of which rise and join at the back. The outer upper surface of the foot, held by the leafy scrolls, is formed by a large concave cabochon, framed by two C-scrolls and surrounded by short leaves, the lowest of which curls over a second cabochon forming the toe. The fall front is framed on all sides by conjoined elongated and lobed scrolls, which are bordered by leaf work and combed flame work. At the center top of the frame is an escutcheon capped by a C-scroll, set above an arrangement of leafy C- and S-scrolls and backed by shellwork. It is pierced at its center by a keyhole.

The frame is set on its lower outer corners with leafy scrolls. At the lower center is a ribbed and winged form chased with flame work and held by double scrolls. Leafy and scrolled concave moldings frame the central drawer. The large escutcheon is composed of a central cabochon pierced with a keyhole and surrounded by ribbed auricular work that descends to form a tongue over a pendant cluster of leaves and berries. To either side are C-scrolls and extending leafy scrolls. The outer drawers are also framed in gilt bronze, similarly composed of leafy and scrolled concave moldings, the side along the top of the drawer being straight. A large cabochon forms the center of the keyhole escutcheon. It is surrounded by C- and S-scrolls enclosing flame work and is supported at its base by a cartilaginous flower form. To the left and right emerge short branches that bear leaves, flowers, and buds. The outer drawer frames and escutcheons are mirror images.

A plain molding outlines the lower profile of the front of the desk and runs down the inner edges of the legs. It is set with small groups of leaves in the areas between the drawers. A similar molding outlines the lower profile of the side of the desk and runs down the outer edges of the legs. The molding is overlaid at its center by a mount consisting of a C-scroll enclosed by an S-scroll, capped by a broad flame motif and supported by leafy scrolls on either side.

The desk is veneered with stylized floral marquetry in kingwood set in the tulipwood background panels on the fall front, sides, drawer fronts, and the top. On the fall fronts two stems are placed to rise from the arrangement of gilt bronze leaves on the lower frame, mentioned above. The twining branches carry leaves, flowers, and tendrils, all growing from a clump of leaves. At the center of the fall front is a loose arrangement of branches also carrying leaves, flowers, and tendrils. The drawer fronts below bear similarly laden branches emerging from either side of the gilt bronze escutcheons. The bombé sides of the desk carry marquetry of four branches of flowers and leaves tied with a crinkled bow (see fig. 8-1). With the exception of the drawer fronts all the marquetry panels are outlined with borders of a darker-colored tulipwood. The hinged flaps lower to reveal a series of nine pigeonholes, five above and four below, above four drawers. The floors of the open compartments are veneered with loose arrangements of kingwood flowers, leaves, and single branches. The four drawer fronts carry small gilt bronze handles in the form of branches of flowers and leaves, and all are veneered with marquetry composed of a single leafy branch with tendrils (fig. 8-4).

The gilt bronze cover plates for the hinges are engraved with acanthus leaves and studs on a stippled ground, surrounded by a burnished border (fig. 8-5). The inside of the fall fronts are lined with green leather.

Figure 8-5

Figure 8-5Marks

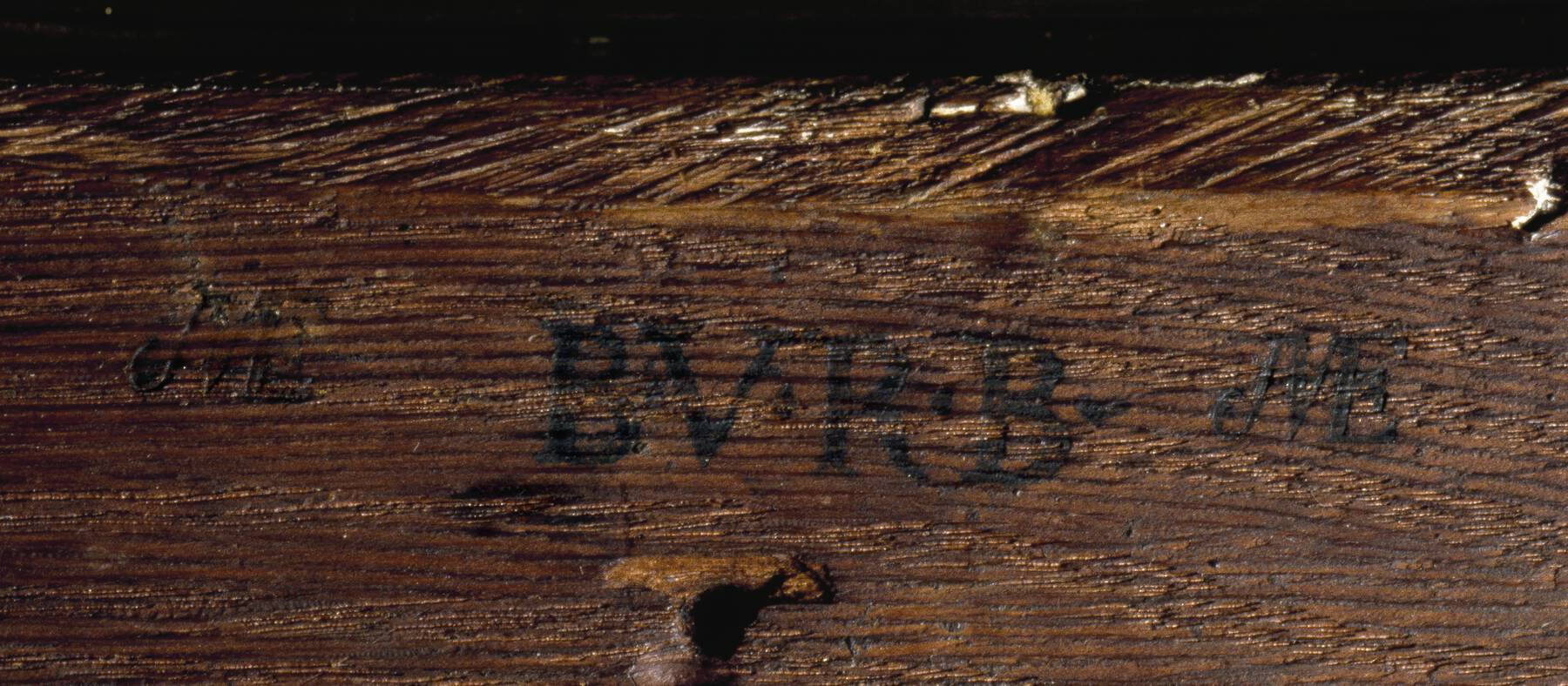

The underside of the upper side rail inside the right front drawer compartment is stamped “B.V.R.B.” once and “JME,” for jurande des menuisiers-ébénistes, twice. The underside of the lower rail beneath the rear central drawer also bears the maker’s stamp, flanked by “JME” stamps (fig. 8-6). On the underside of the carcass near the front side of the desk are seven red wax seals of the Duke of Argyll (fig. 8-7).

Figure 8-6

Figure 8-6 Figure 8-7

Figure 8-7Commentary

This monumental and unique double desk was made by Bernard II van Risenburgh probably in the mid-1750s and can be compared to a few other opulent pieces made by this master.1 A large armoire set with panels of red lacquer made for Jean-Baptiste de Machault d’Arnouville in the collection of the musée du Louvre probably dates from this period (see fig. 1-6),2 and a large secrétaire-bibliothèque now in the musée de Tessé in Le Mans was delivered by Lazare Duvaux to the Grand Trianon in 1755 (see fig. 2-6). The fall front of this secrétaire is veneered with a bunch of flowers tied with a ribbon that is similar in design to that found on the sides of the Museum’s desk.3 The most similar in form is a large bureau à pente belonging to Neil Archibald Primrose, seventh Earl of Rosebery and third Earl of Midlothian, at Dalmeny House in Scotland (fig. 8-8).4 Veneered with floral marquetry in bois de bout on a tulipwood ground, it bears mounts of the same models at the upper corners, at the center of the top, at the upper corners of the legs, and on the feet. This desk, somewhat shorter in width, carries only two drawers in its frieze below the fall front, and consequently the lower profile beneath them differs. The original provenance of the Rosebery desk is not known, but like the Museum’s desk, it must have been made for an extremely rich client of the marchand-mercier Duvaux or Simon Philippe Poirier.

Figure 8-8

Figure 8-8It is likely that the Museum’s desk is a development of this single-sided bureau, and it carries extra embellishments such as drawers of solid mahogany with gilded lock boxes and engraved cover plates to the hinges (see fig. 8-5).5 Both desks derive from the smaller bureaux à pentes made by this master throughout his career.6 While a few other double-sided desks exist, they are either of differing form or of doubted authenticity.7

When the desk was acquired by J. Paul Getty in 1952, it came with a family tradition as to its provenance, which has since been disproved. It was said that the desk had been acquired in Paris in 1760 by Lady Elizabeth Gunning (1733–1790), the wife of James George Hamilton, sixth Duke of Hamilton (1724–1758). Following his death in 1758, she married John Campbell, fifth Duke of Argyll (1723–1806) in 1759. While it is known that the duchess was in Paris in 1760 and in 1763, no mention of such a purchase is mentioned in the family’s documents.8 An even more fanciful idea has been suggested, namely, that the desk was made for the twin daughters of Louis XV, Louise-Élisabeth, Duchess of Parma, and her sister, Madame Henriette.9 Apart from the fact that the latter died in 1752, the desk bears no royal inventory number, and it is not found in the Registers of the Garde-meuble, its massive form alone would, it seems, make it unsuitable for the use of young girls. In addition, as the Duchess of Parma was married in 1739 and left Versailles that same year, although she did make return trips to Versailles, it would seem unlikely for such a commission to have been made for her and her unmarried sister a decade later, when the desk appears to have been made.

In 1991, Patrick Leperlier discovered a description of a similar desk in the inventory taken in 1795 after the execution of the fermier-général Louis Balthazar Dangé de Bagneux (1739–1794):

19 Frimaire an IV.

[No.] 108––Item un secrétaire en tombeaux à deux faces de bois rose et palissandre plaqué à fleurs à trois tiroirs de chaque côté avec ornements et entrées de serrure de cuivre doré prisé deux cents quarante livres.10

As no other desk of this description is known to exist, it is very likely that this is the Museum’s desk. Louis Balthazar possibly purchased the desk at the death of his uncle François Balthazar Dangé du Fay (1696–1777) from the contents of his home.11 Dangé du Fay lived in the hôtel de Villemaré, 9, place Louis le Grand (now place Vendôme), and the desk stood in his cabinet bibliothèque in the entresol. When the seals were placed on the contents of the hôtel at the death of his wife, Anne (née Jarry), on March 22, 1772, the conseiller du Roy commissaire au Châtelet Pierre Thierion stated:

avons pareillement apposés nos scellés aux bouts et extrémités de quatre bandes de papier traversantes les ouvertures et fermeture de trois tiroirs et une bascule d’un bureau en secrétaire de bois de raport ornés de ses fontes dorés d’or moulu et sabots de piés de biches l’aut[re] partie dudit bureau pareille ouverte et vuide.12

In the inventory taken five days later, Leperlier found a further description of the desk:

le 1er avril [ . . . ]

Dans le cabinet de Mr. Dangé aux entresols ayant vue sur lad. place de Louis le Grand [ . . . ]

[ . . . ] un secrétaire en tombeau aussi de bois de placage à fleurs avec ornemens, entrées de serrure sabots filets et autres garnitures dorées d’or moulu avec son serre-papier de pareil bois garni de huit cartons de maroquin rouge à fleurs d’or & petits boutons de cuivre [ . . . avec une commode à cylindre et trois tables prisés] 1600 [livres].13

The mention of a serre-papiers is puzzling, as there is nowhere on the desk where it could have stood. Perhaps it was set on another piece of furniture en suite. It does not appear in further descriptions of the desk in the inventory of Dangé du Fay himself, who died in 1777.14 Shortly after his death, a public sale of the furniture was held that brought 109,727 livres for his heirs, the five children of his brother, who had died in 1741.15 It is apparent that the desk was bought back at the sale by Dangé du Fay’s nephew Louis Balthazar Dangé de Bagneux, who had been associated with his uncle, a fermier-général from 1736 until his death. Louis Balthazar was trésorier général des Invalides in 1758, a fermier-général adjoint from 1768 to 1777, and titulaire from 1778 to 1791.16 His widow, Anne-Marie Sanson, died in 1796, two years after his execution, and her heir was their daughter Marie-Émilie Françoise Dangé de Bagneux Creuzé.17 It is likely that the desk made its way to Inveraray Castle in the early decades of the nineteenth century.

In 1978, Ian Campbell, twelfth Duke of Argyll (1937–2001), discovered the original bill for the desk. Unfortunately, the bill was misfiled in the Inveraray archives before he could disclose the name of the seller and could not be found.18 In the book Collector’s Choice: The Chronicle of an Artistic Odyssey through Europe, J. Paul Getty and Ethel Le Vane give the background for his acquisition of the desk in 1952.19 In 1951 Getty was having lunch at Whites with the eleventh Duke of Argyll, Sir Ian Douglas Campbell (1903–1973). The duke, who had recently succeeded to the title, told him that he had also inherited “the usual quota of uninteresting paintings and unimportant French furniture” and invited Getty to spend the weekend at Inveraray. Getty, having “too many calls” on his time, declined. After lunch he met with his friend Sir Robert Abdy, “a famous connoisseur of French furniture” (and a dealer) and told him about the duke’s offer. Abdy assured Getty that the duke could not possibly have any furniture of great importance or value. Abdy seems to have then immediately gone to Inveraray, where he saw the double desk. He bought it and sold it to Rosenberg & Stiebel in New York. Eventually Getty tracked it down and paid $35,000 for it. He imagined that he could have paid much less if he had accepted the duke’s invitation.

Provenance

By 1772–77: possibly François Balthazar Dangé du Fay, French, 1696–1777 (Hôtel de Villemaré, place Louis le Grand, now place Vendôme, Paris, France), sold to his nephew and heir, Louis Balthazar Dangé de Bagneux, 1777;20 1777–94: possibly Louis Balthazar Dangé de Bagneux, French, 1738–1794, by inheritance to his wife, Anne-Marie Sanson, 1794;21 1794–96: possibly Anne-Marie Sanson, French, died 1796, by inheritance to her daughter, Marie-Émilie Françoise Dangé de Bagneaux Creuzé, 1796;22 1796– : possibly Marie-Émilie Françoise Dangé de Bagneaux Creuzé, French (Rue Saint-Honoré, Paris, France);23 early nineteenth century– : possibly Dukes of Argyll, Scottish (Inveraray Castle, Argyll, Scotland); –1951: Ian Douglas Campbell, eleventh Duke of Argyll, Scottish, 1903–1973 (Inveraray Castle, Argyll, Scotland), sold to Sir Robert Henry Edward Abdy; 1951– : Sir Robert Henry Edward Abdy, fifth Bart., English, 1896–1976 (London, England), sold to Rosenberg & Stiebel, Inc.; –1953: Rosenberg & Stiebel, Inc. (New York, NY), sold to J. Paul Getty; 1953–70: J. Paul Getty, American, 1892–1976, donated to the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1970.

Exhibition History

Louis XV: Un moment de perfection de l’art français, Hôtel de la Monnaie (Paris), December 1, 1974–April 30, 1975.

Bibliography

, 261–63; , 118, 121, 127, fig. 10; , 78, ill.; , 43, ill.; , 116–17; , 78, fig. 3; , 145–47, 151, ill.; , 465–66, ill.; , 327–28, no. 430; , 190; , 112; , 50, 140, 152, 267, fig. 3; , 66, fig. 30; , 130, 135, 139, ill.; , 142, under no. 68; , 19, 133, 222, fig. 3; , 36, no. 41; , 124–26, ill.; , 24, no. 41.

- G.W.

Technical Description

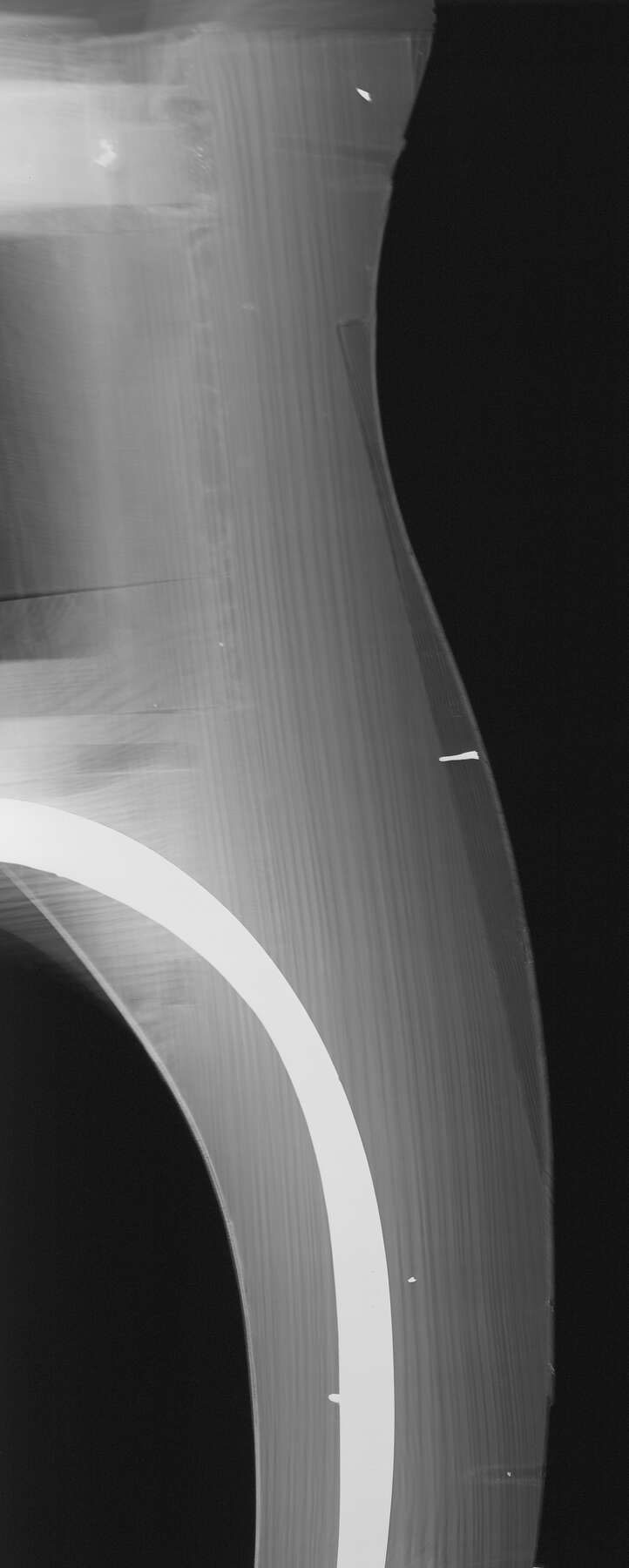

All the structural elements of the carcass are made of white oak. The legs, or corner posts, are made up of at least two pieces of oak laminated together side by side to make up the bulk of the leg form. X-radiography shows that these posts only rise up to the level of the writing surface. The case bottom is made in frame-and-panel construction, with three panels corresponding to the three drawer compartments. The front and rear rails of the case bottom appear to be set into the corner posts with shouldered mortise-and-tenon joints; the tenons are flush with the inside surface of the rail. The bulk of the rails are made of single pieces of oak approximately 8 cm high by 4 cm deep, but to increase the depth along the center section, three separate pieces of oak approximately 1 cm thick have been laminated on the outside faces. The rails have been chamfered along the lower outer edges and carved to accommodate the curved and protruding edges of the drawer fronts (fig. 8-9).

Figure 8-9

Figure 8-9The side rails of the case bottom, running between the front and back legs, are approximately 4 cm thick and 6.7 cm wide and set into shallow horizontal dadoes in the front and rear posts.24 In an unusual departure from standard Parisian methods, these rails are deeply rabbeted on the upper inside corners so that they form both the drawer supports and the drawer guides. The medial rails of the case bottom frame-and-panel assembly are attached to the front and rear rails with unusual mortise-and-tenon joints. The tenons are flush with the lower face of the rails, and, based on the presence of paired scribe marks on the inside surface of the front and rear rails, they appear to be shouldered on both sides. Like the side rails, the medial rails are also made of thick single pieces of oak and are rabbeted along their top edges so that they form both the drawer supports and the drawer guides.

The three panels of the case bottom are each made of two quartersawn boards arranged with the grain running from front to back. On both the interior and exterior surfaces these boards very clearly show tool marks from the subtly curved blade of a scrub plane. On the bottom or exterior, the edges of the panels are raised with simple cove moldings, cut with a molding plane. This type of panel raising is employed in only one other piece in the collection, also stamped “B.V.R.B.,” the red lacquer commode (cat. no. 6). The interior vertical dividers that separate the three drawer compartments are glued to the medial rails of the case bottom and to the rails of the writing surface compartment above; there is no joinery fastening these panels. The exterior stiles that separate the drawers at the front and rear of the commode are mortise and tenoned into the rails above and below. The tenons here are flush with the back surface of the stiles.

At the level of the writing surface on either end of the desk, there are heavy rails running between the front and rear posts, just inside the case sides. These rails are very thick—about 4.5 cm from top to bottom—and they are apparently attached to the front and rear posts with shallow horizontal rabbet-and-dado joints. The rails, which also serve as kickers for the side drawers, are grooved on their interior faces; the long, broad planks that form the writing surface above the drawers are rabbeted to fit these grooves. Above the central drawer, a stick of oak, running from front to back, is glued and lapped to the underside of the writing surfaces to act as a kicker.

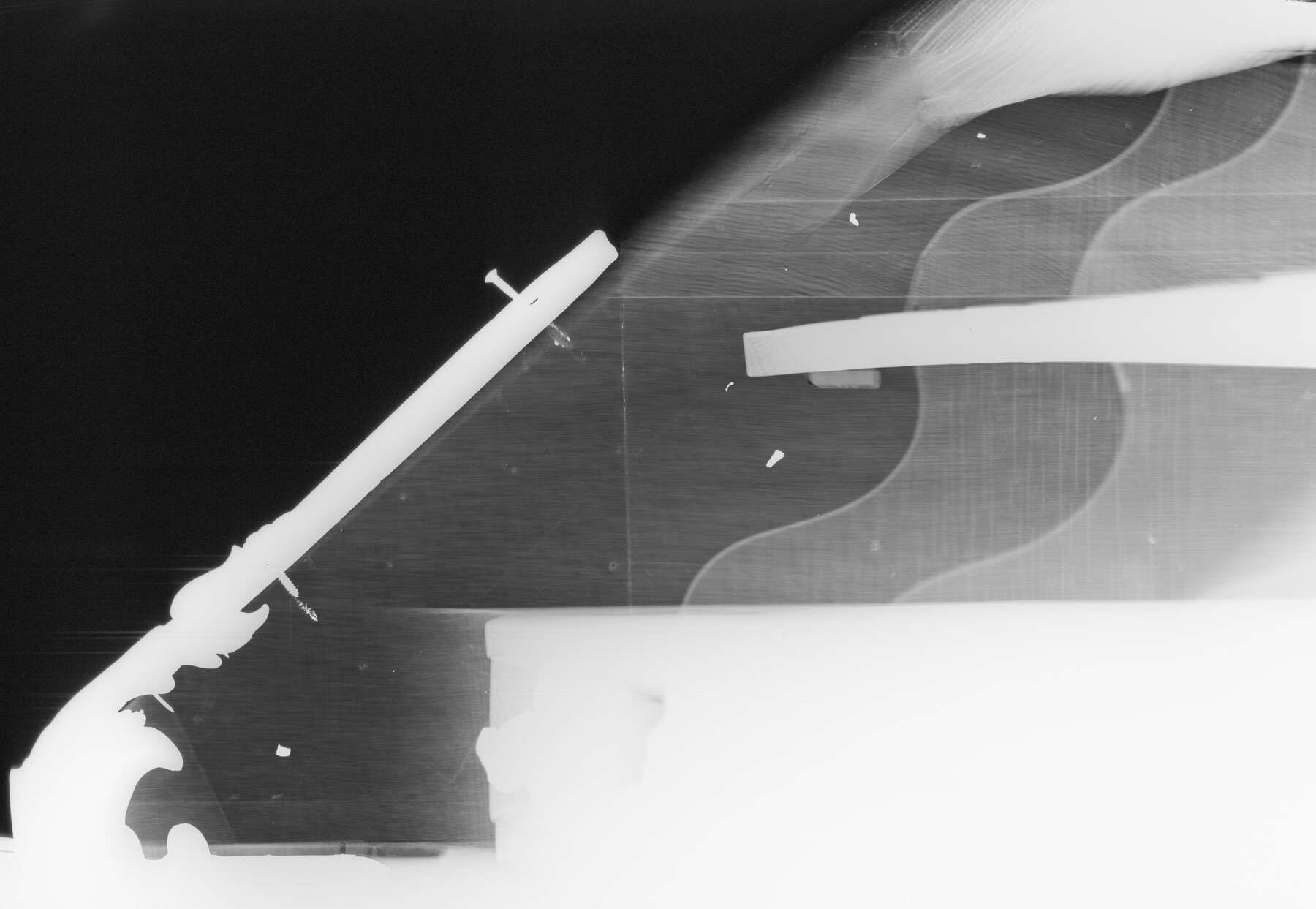

The lower sections of the sides of the case form structural rails, mortise and tenoned into the legs at front and rear. Above these sections, X-radiography shows a complex patchwork of oak blocks, overlapping the tops of the legs and stacked and laminated together in at least two layers to form the gracefully curved form of the upper sides (fig. 8-10). The top of the desk is made of a single long board, attached to the sides with a rabbet-and-groove joint; narrow blocks are glued to the underside to thicken the front and rear edges.

Figure 8-10

Figure 8-10The repeated use of rabbet-and-dado joints (rather than the more common tongue and groove) is an unusual and distinctive feature of this desk. In addition, many of the mortise-and-tenon joints in this piece are made in an analogous way; that is, one face of the tenon is flush with the face of the rail rather than recessed on both sides. These variant joinery types were probably faster and easier to cut than their more traditional counterparts, but they are generally considered inferior in strength.

Below the top, a vertical dividing panel runs the length of the case, serving as a back for the pigeonhole and drawer compartments on both sides. This panel is set into dadoes in both of the case sides but is not attached to the case top. X-radiographs of the fall fronts show that they are each made of four long boards, butt joined, and capped with breadboard ends attached with tongue-and-groove joints.

The pigeonholes and drawers on both sides of the desk are built as separate removable units (fig. 8-11). Each unit is made of three horizontal members, a narrower one above made from a single board and two wider ones below, each made from two boards laminated together. The ends of the two lower horizontal members are rabbeted, and the tongues are fitted to grooves on the sides of the case. The vertical partitions are made with the grain of the oak substrate running vertically, allowing them to expand and contract in concert with the horizontal members. The partitions are attached at top and bottom with single-faced sliding dovetails that were cut after the individual elements had already been veneered. Many, perhaps half, of these dovetails have been modified in an unusual manner; they have been converted into wedged dado joints. It is not clear whether these carefully executed modifications were made during the original construction or were part of a restoration campaign. The former appears to be more likely as there is very little evidence of significant restoration to the piece, with the exception of the finish.

Figure 8-11

Figure 8-11All of the drawers of the double desk, both the large exterior drawers and the smaller interior ones, are made in a similar manner. The drawers are made primarily of high-quality mahogany with a striped figure. Only the drawer fronts are made of oak, and even these are veneered with mahogany on their top and inside faces. The top edges of the drawer sides and backs are gently rounded. The drawer bottoms are set into rabbets on all sides and then covered with mitered strips glued around all four edges. The grain of the drawer bottoms runs from side to side.

It appears that several modifications were made to the design of the desk during its fabrication. Perhaps the most significant of these was a change in the number of large exterior drawers on each side from two to three. The evidence that such a transformation occurred is apparent when the center drawers on either side are pulled out. Long mortises have been cut into the rails above and below the central drawer front that were evidently intended to secure a single, wide stile that would have separated two large drawer compartments where there are now three, an arrangement very similar to that of the Dalmeny desk discussed in “Commentary” above. This suggests that the Getty desk was made later as an enlarged (and two-sided) version of that desk but that as it was being built it became clear that its greater length was better suited to division into three drawers rather than two.

A second modification concerns the spacing of the pigeonholes in the interior of the desk. When the front shelf unit is removed from the desk, an extra set of four sliding dovetail mortises can be seen on the rear edge of the upper shelf (see fig. 8-11). The outer mortises are positioned directly above the outer dividers of the levels below. The inner mortises are spaced equally in between, slightly toward the center of the current dividers. On the rear shelf unit the extra mortises are not present, suggesting that the front unit was built first using the extra mortises and then the design was revised, shifting the dividers into their current, equally spaced, arrangement. Furthermore, sliding dovetail mortises have been cut into the underside of the case top, on both sides, directly above the current position of the upper dividers. It appears that at some point the maker intended the dividers to be joined to the case top; however, this plan too seems to have changed during fabrication. The dividers were in fact left without dovetails on top, allowing the entire unit to slide freely in and out of the desk compartment.

Yet another design modification during construction appears to have been made to the legs. X-radiographs of the upper sections of the legs show that blocks of wood have been inserted to enlarge the swell of the knees behind the pierced sections of the corner mounts (fig. 8-12). The original mass of wood from which the legs were cut would clearly have been large enough to create the final form; this implies that the legs were first cut to shape, and then, probably when the mounts were being fitted, it was decided to augment the knees to conform more closely with the interior surface of the pierced mounts.

Figure 8-12

Figure 8-12The exterior and interior of the desk are veneered in tulipwood, kingwood, and bloodwood. This choice of veneer woods is consistent with other pieces made by Van Risenburgh. The stylized flowers and leaves of the marquetry are made of kingwood that is obliquely cut to yield so-called oyster or sausage veneer; many of the larger flowers are made of two symmetrical, book-matched pieces. The branches are made of numerous small quartersawn veneer elements, and on the end panels, the sprays of flowers are held together by a ribbon of bloodwood. The floral elements are set into a background of light-colored tulipwood, which is framed with borders of darker-colored tulipwood that surround the drawers and extend down the legs of the table. The chamfered inner corners of the legs are veneered in kingwood, and the backs of the legs are in cross-grain bloodwood. The front edges of the drawer and pigeonhole assemblies are also cross banded with bloodwood veneer.

The condition of the marquetry decoration is generally very good, with few obvious replacements of veneer. The exterior has been significantly faded by light, but the interior has remained extraordinarily well protected and reveals the strong contrast of color and tone that was originally intended.

The extremely high quality of the fitting of the kingwood elements into the tulipwood along with examination of X-radiographs suggests that the marquetry was cut with a fretsaw using the “conic cutting” technique and was likely assembled in large sections prior to being glued onto the carcass. The more common method of producing marquetry at the time of the manufacture of this desk is called the piece-by-piece technique. In this method, the sheets of background veneer are first glued one by one on the finished carcass of a piece of furniture and the marquetry elements are inlaid subsequently. Small iron nails are placed alongside each piece of background veneer to prevent it from sliding out of position during gluing and clamping. These veneer pins are removed once the glue has dried, and the next piece of veneer is then glued. On this desk, however, X-ray examination of the fall fronts and sides revealed no veneer pin holes. In the piece-by-piece method, the inlay work is done using a knife called a shoulder knife. The difficulty of using this tool often results in small slippages, resulting in unwanted cuts referred to as shoulder knife marks. A thorough examination of the Getty double desk under a microscope revealed no shoulder knife marks on any area of the marquetry, suggesting that the shoulder knife was not used on this piece. The examination did reveal connecting cuts between separate kingwood elements. This, along with the rounded shape of the kingwood elements, suggests that the holes cut in the tulipwood background to receive the kingwood elements were created using a fretsaw before the background was glued onto the solid wood carcass.

Conic or bevel cutting is similar to boulle marquetry or stack cutting, where multiple veneers are cut simultaneously and assembled into finished sections prior to gluing; however, unlike boulle marquetry, the saw blade is angled slightly and the kerf created by the saw blade disappears when the top piece is dropped into the hole created in the lower veneer. This technique results in flawless joins; however, unlike standard boulle work, only a single pair of veneers can be cut at a time. Bevel marquetry cutting had almost certainly been only recently developed at the time of the manufacture of this desk and is seen on other pieces in the Museum attributed to Van Risenburgh and his contemporaries (see, e.g., the writing table, cat. no. 18). However, gluing very large sheets of finished marquetry onto compound-curved surfaces without the aid of veneer pins is technically complex and very unusual in the mid-eighteenth century.

The inner surfaces of the fall fronts are covered with a broad field of green-stained leather framed with tulipwood. Each field is composed of two pieces of leather, joined at the center, without any tooling. The leather is clearly old; however, it is difficult to say whether or not it is original.

The desk is stamped twice with the mark of Van Risenburgh. The first stamp is on the underside of the lower rail, beneath the center drawer on the rear side. The location of the second stamp is rather more unusual: it is in the interior of the right front drawer compartment, on the underside of the upper side rail. The position of this stamp would make it extremely difficult, if not impossible, to strike it after the desk had been fully assembled, suggesting that it was done while the desk was still under construction. Both stamps are struck and inked as is typical of Van Risenburgh. The stamps were compared by means of high-resolution rectified photographs to the stamps on the Museum’s display cabinets (cat. no. 2) and lacquer commode (cat. no. 5). The marks are so nearly identical that they were almost certainly struck with the same stamp.

The current finish on the exterior of the desk is a cellulose nitrate lacquer of recent origin and was applied during a restoration campaign in 1973–74.25 This lacquer was applied rather thickly and then sanded and polished to produce a very flat and uniform surface. The coating has now yellowed and opacified, somewhat obscuring the color and contrast of the albeit faded marquetry. On the interior of the desk the situation is rather different. Examination under ultraviolet illumination shows clearly that an earlier restoration (of unknown date) involved the brush application of an orange-fluorescing coating (presumably shellac) over most of the interior marquetry. The restorer’s brush failed, however, to reach the back of the pigeonholes, and as a result, there remains along the rear edge an irregular band of apparently unrestored veneer (fig. 8-13). The unrestored passages appear to have only a very thin coating, which fluoresces very weakly in a pale greenish color. Minute scrapings of this coating were analyzed by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), and this analysis suggests very strongly that the primary component is beeswax. It would appear, then, that at least the interior was originally polished with wax, suggesting the possibility that the exterior was originally similarly polished.

Figure 8-13

Figure 8-13The gilt bronze mounts on the desk are of very high quality and are in an excellent state of preservation. The chasing of the matted surfaces is comparatively uniform, though it is very carefully executed. These matte passages contrast dramatically with the long, broad areas of highly burnished gilding. Analysis of the gilding by X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) confirms that it contains significant amounts of mercury and is comparatively thick, suggesting that it is traditional mercury amalgam gilding.

Many smaller cast elements have been assembled into large unified mounts by soldering them together. The mounts around the edges of the exterior drawers, for example, are each assembled from four separate castings. XRF analysis of the soldering metal used to join the segments shows it to be a very high zinc brass alloy (> 34%) that contains traces of cadmium. This is unusual in the mid-eighteenth century and suggests that the metal used was “spelter” brass made using metallic zinc, a rare and expensive commodity in the eighteenth century. Standard solder of the period was so-called cementation brass containing approximately 30% zinc. The advantage of using the costlier spelter brass would surely have been its lower melting temperature, making the extensive soldering done on the mounts easier and less likely to damage the castings.

Sixteen gilded bronze elements were removed from the desk and analyzed on their back surfaces by XRF to determine the general composition of their alloys. All are cast from brass with moderate zinc content ranging from about 19 to 27%. This is slightly higher than normal for the period, but the concomitant use of high zinc soldering metal ensured that these mounts could still be safely joined. The cast elements also contain typical eighteenth-century amounts of minor elements and impurities, including 1 to 2% lead and approximately 1% tin, as well as minor amounts of iron, nickel, silver, and antimony.26

The locks of the exterior drawers are mounted in an unusual fashion. The locks themselves are roughly finished iron mechanisms with double-throw action and twin bolts. These are mounted to a pair of horizontal oak blocks that are glued and nailed to the inner face of the drawer fronts (fig. 8-14). The elegant gilt bronze lock boxes are separate, cast elements that are then fitted over the lock assemblies and mounted directly to the drawer fronts (fig. 8-15).

Figure 8-14

Figure 8-14 Figure 8-15

Figure 8-15The hinges for the fall fronts are also mounted in an unusual and somewhat analogous fashion. At first glance, these substantial hinges appear to be made of engraved and gilt bronze. In fact, however, the kidney-shaped decorative plates are merely covers for the functional iron hinges concealed below (fig. 8-16). At the center of the lower edge of each fall front, a gilt bronze stop plate with a stub tenon is designed to engage the mortise of a mating plate mounted in the case, just above the center drawer. This extra hardware is intended to help support the fall front and to keep it aligned with the writing surface of the desk proper. Over the years, however, the case has sagged somewhat so that when the fall fronts are opened the stop plates do not mate.

Figure 8-16

Figure 8-16In order to help confirm the age of the desk, a thorough dendrochronological (tree ring dating) study of the piece was undertaken. Eighteen individual pieces of wood from the structure and the drawers were identified as having areas of exposed end grain suitable for analysis. Most of these were pieces from the removable drawer and pigeonhole assemblies, but the wood of the legs was also used. High-resolution macrophotographs were made of the end grain, and all visible rings were measured to the nearest hundredth of a millimeter. Analysis of the ring patterns in the wood show that the youngest existing ring dates to 1730 and that the oak for the desk originated in northeastern France. Unfortunately, no sapwood remains on any of the pieces studied, and without sapwood it is difficult to establish a terminus ante quem for the date the tree(s) were felled. However, if one assumes that the existing boards had the sapwood neatly trimmed with the loss of only several rings of heartwood, then, since oak is known to have an average of 15 sapwood rings,27 one may surmise that the tree was likely to have been cut around the late 1740s.28 Allowing for seasoning of the timber and fabrication of the piece, the dendrochronology results are consistent with fabrication of the desk in the mid-1750s.29

- A.H.,

- Y.C.

Notes

For information on Bernard II van Risenburgh, see primarily , 183–99; , 56–63. See also Daniel Alcouffe, in , 323–24. ↩︎

On deposit at the château de Versailles since 1796. Acc. nos. V5090 and OA 9599. See Daniel Alcouffe, in , 324–25; , vol. 2, 50–52, no. 8; , 154–55, no. 40 (A. Pradère), and 156–57, no. 41 (T. Wolvesperges); , 55. ↩︎

Musée de Tessé, Le Mans, inv. no. 1906.29.66. Daniel Alcouffe, in , 325, no. 427; , illus. between 144–45, 241–42, no. 074; , 198, fig. 190; , 158–59, no. 42 (G. Mabille). A “B.V.R.B.” stamp was discovered in the course of a restoration in the early 1990s. See . ↩︎

, 551–52, no. 489. Measurements: 3 ft. 5 in. x 4 ft. 8 in. x 2 ft. 2 1/2 in. (104 x 142.2 x 67.5 cm). ↩︎

The hinges of the Dalmeny desk do not possess plates, and it is likely that the surface of the fall front has been reveneered. ↩︎

See a. The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Legion of Honor, acc. no. 1926.91. Veneered with trellis marquetry. (H: 3 ft. 3 in., W: 2 ft. 6 in., D: 1 ft. 5 1/4 in.; 99.1 x 76.2 x 43.8 cm.)

b. Versailles, inv. no. V 5268. See , 192, fig. 179; , vol. 1, 108–11, no. 29.

c. The National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Widener Collection, inv. no. 1942.9.419. With bois de bout marquetry (H: 2 ft. 7 1/2 in., W: 1 ft. 9 in., D: 1 ft. 2 1/8 in.; 80 x 53.3 x 35.8 cm). , 18, no. C-272.

d. Painted in blue European lacquer with Japanese motifs in gold and brown at the Galerie Steinitz, Paris. The gilt bronze mounts are struck with the crowned C, dating the piece to between 1745 and 1749. Illustrated in , 192, fig. 178.

e. Veneered with black and gold Japanese lacquer, the gilt bronze mounts are struck with the crowned C. Sold by Beaussant Lefèvre at Drouot Richelieu, Tableaux anciens et modernes, objets d’art et de très bel ameublement, November 24, 1995 (Paris: Drouot Richlieu), 1995, lot 177 (88 x 98.5 x 50 cm).

f. Veneered with black and gold Japanese lacquer with mounts of the same model and similar dimensions to (e) but unstamped (87 x 99 x 50 cm), in the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum. See , 156–59, no. 12, acc. no. 285. ↩︎

a. A simply decorated double-sided desk is in the musée national Magnin in Dijon. It bears mounts only at the feet and keyholes and is veneered with bois de rose en aile de papillon. It is stamped “B. Durand,” for Bon Durand (m. 1761) (88.5 x 69.5 x 52.5 cm). See , 26, no. 6.

b. A large double desk (described as a secrétaire double en dos d’âne) veneered with floral marquetry in rosewood, with a pronounced kneehole, flanked by drawers. The fall front is decorated with an untraceable and probably imaginary coat of arms as well as the monograms SA and GA. It is inscribed beneath, “Facit [sic] p. A. Augustii Le 11e 9bre 1768,” sold, Sotheby’s, Good Continental Furniture, Works of Art, Tapestries and Oriental Rugs and Carpets, November 30, 1979 (London: Sotheby’s, 1979), lot 302 (3 ft. 10 in. x 4 ft. 10 in. x 3 ft. 3 in.; 117 x 147 x 99 cm). Illustrated in “Notable Works of Art Now on the Market,” Supplement, Burlington Magazine 119, no. 897 (December 1977), pl. XV, as the property of Edmund Joachim Kratz, Hamburg.

c. Sold from the collection of Sir Everard Radcliffe: Christie’s, The Remaining Contents of Rudding Park, Harrogate, Yorkshire, October 16–17, 1972 (London: Christie’s, 1972), lot 75, pls. 15 and 16 (H: 3 ft. 8 in., W: 6 ft. 8 in.). Formerly in the collection of the Dukes of Newcastle. Considered to be of nineteenth-century date.

d. A desk formerly in the collection of Charles de Beistegui, veneered with plain veneers and with scrolling ribbons of a darker wood, with a pronounced kneehole flanked by drawers. Sold, Palais Galliéra, Objets d’art et de très bel ameublement: Biscuit émaillé bleu de la chine, porcelaine de la compagnie des Indes, tapis, tapisseries, June 9–10, 1976 (Paris: Palais Galliéra, 1976), no. 208 (113 x 197 x 104 cm). Illustrated in , 11. Considered to be of nineteenth-century date.

e. An apparently loose copy of the Museum’s desk, made in the nineteenth century, sold, Christie’s, The Nineteenth Century: European Ceramics, Furniture and Works of Art Including Sculpture from Nidd Hall, Yorks. September 24, 1987 (London: Christie’s, 1987), lot 321.

f. A double-sided secrétaire stamped “FEURSTEIN,” for Joseph Feurstein (master in 1767), veneered with tulipwood and kingwood in bois de bout marquetry, sold, Christie’s, The Dr. Anton C. R. Dreesmann Collection: European Furniture and Chinese Export Porcelain Including Clocks, Antiquities, and Works of Art, April 10, 2002 (London: Christie’s, 2002), lot 241. ↩︎

, 786–87; correspondence with Mrs. Diana Short of the Argyll Estates Office, Cherry Park, Inveraray, Argyll, August 21, 1978, in the files of the Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

, 78. ↩︎

Paris, Archives nationales de France, Minutier central, LXXXVII, 1276, 19 frimaire an IV (December 10, 1795), inventory after the death of Louis Balthazar Dangé de Bagneux. ↩︎

Correspondence with Patrick Leperlier, April 18, 1991, in the files of the Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

Paris, Archives nationales de France, Y 10902 A, March 22–24, 1772: “Sçellé après le décès de Madame Dangé en son hôtel place Vendôme et par suitte à Fouilleuse, Puteaux et Groslay.” ↩︎

Paris, Archives nationales de France, Minutier central, LXXXVII, 1138, March 27, 1772, inventory after the death of Anne Dangé (née Jarry). ↩︎

“[ . . . ] dans le cabinet en suite [du premier cabinet de M. Dangé ayant vue sur la place] [ . . . ] 125 un secrétaire en tombeau en bois de rose et palissandre avec fonte et entrées de s[err]urres de cuivre doré d’or moulu [ . . . avec une commode, un petit bureau, et une table prisés le tout ensemble . . . ] 1600 [livres].” Paris, Archives nationales de France, Minutier central, LXXXVII, 1165, March 17, 1777, inventory after the death of François Balthazar Dangé du Fay. ↩︎

, 193. ↩︎

Paris, Archives nationales de France, Minutier central, LXXXVII, 1277, 6 ventôse an IV (February 25, 1796), inventory after the death of Anne-Marie Sanson, widow of Louis Balthazar Dangé de Bagneaux. ↩︎

Correspondence with the author, August 21, 1978, in the files of the Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

, 261–63. ↩︎

A secrétaire en tombeau is recorded in the inventory after the death of his wife, Anne (née Jarry), dated March 27, 1772 (Paris, Archives nationales de France, Minutier central, LXXXVII, 1138), and also in the inventory after his own death, dated March 6, 1777 (Paris, Archives nationales de France, Minutier central, LXXXVII, 1165, inv. item no. 125). ↩︎

A secrétaire en tombeaux à deux faces is recorded in the inventory after his death, dated 19 frimaire an IV (December 10, 1795) (Paris, Archives nationales de France, Minutier central, LXXXVII, 1276, inv. item no. 108). ↩︎

Recorded in the inventory after her death, dated 6 ventôse an IV (February 25, 1796) (Paris, Archives nationales de France, Minutier central, LXXXVII, 1277, verso of page with inventory items adding up to 14,191 livres). ↩︎

Recorded as the only heir in the inventory after the death of her mother, Anne-Marie Sanson, dated 6 ventôse an IV (February 25, 1796) (Paris, Archives nationales de France, Minutier central, LXXXVII, 1277, p. 1). ↩︎

The measurements of all the case bottom rails conform well with eighteenth-century French units of measure: 4 cm equals 1 1/2 pouces (Paris in.), 6.7 cm equals 2 1/2 pouces, and 8.1 cm equals 3 pouces. ↩︎

The lacquer was analyzed using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) in 1999. FTIR analysis was conducted by Herant Khanjian of the Getty Conservation Institute. ↩︎

For details of the XRF analysis see the X-ray Fluorescence Analysis Report by Arlen Heginbotham, on file in the Decorative Arts and Sculpture Conservation Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

. ↩︎

If more rings of heartwood were trimmed off, the estimated date would be correspondingly later. ↩︎

For a more detailed discussion of the dendrochronological analysis, see the report by Didier Pousset and Christine Locatelli, on file in the Decorative Arts and Sculpture Conservation Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

Bibliography

- 18th Century: Birth of Design 2014

- 18th Century: Birth of Design: Furniture Masterpieces 1650–1790. Exh. cat. Paris: Éditions Faton, 2014.

- Alcouffe 1990

- Alcouffe, Daniel, ed. Nouvelles acquisitions du département des Objets d’art, 1985–1989. Paris: Réunion des musée nationaux, 1990.

- Alcouffe 1974

- Alcouffe, Daniel. “Hôtel de la Monnaie, Louis XV: Un moment de perfection de l’art français.” La Revue du Louvre et des Musées de France 24, no. 6 (1974): 457–67.

- Baroli 1957

- Baroli, Jean-Pierre. “Le mystérieux B.V.R.B. enfin identifié.” Connaissance des Arts 61 (March 1957): 56–63.

- Boutemy 1958

- Boutemy, André. “Les vraies formes du ‘bureau dos d’âne.’” Connaissance des Arts 77 (July 1958): 38–43.

- Bremer-David et al. 1993

- Bremer-David, Charissa, et al. Decorative Arts: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue of the Collections of the J. Paul Getty Museum. Malibu, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1993.

- Cadilhon 2003

- Cadilhon, François, ed. La France d’Ancien Régime: Textes et documents, 1484–1789. Bordeaux: Presses Universitaires de Bordeaux, 2003.

- Charles 1989

- Charles, Jacques, ed. De Versailles à Paris: Le destin des collections royales. Exh. cat. Paris: Centre culturel du Panthéon, 1989.

- Chaserant, Lauwick, and Payet 1995

- Chaserant, Françoise, Béatrice Lauwick, and Roch Payet. “Le secrétaire de B.V.R.B. conservé au musée de Tessé du Mans.” Revue du Louvre, Revue des Musées de France 45, no. 1 (February 1995): 68–75.

- Coutinho 1999

- Coutinho, Maria Isabel Pereira. 18th-Century French Furniture. Lisbon: Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, 1999.

- “Entretien avec Charles de Beistegui” 1952

- “Entretien avec Charles de Beistegui.” Connaissance des Arts 3 (May 1952): 10–13.

- Frégnac and Meuvret 1965

- Frégnac, Claude, and Jean Meuvret. French Cabinetmakers of the Eighteenth Century. Paris: Hachette, 1965.

- French Connections . . . 1985

- French Connections: Scotland & the Arts of France. Edinburgh: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, Royal Scottish Museum, 1985.

- Getty and Le Vane 1955

- Getty, J. Paul, and Ethel Le Vane. Collector’s Choice: The Chronicle of an Artistic Odyssey through Europe. London: W. H. Allen, 1955.

- Getty 1963

- Getty, J. Paul. Chefs-d’oeuvre de la collection J. Paul Getty. Monaco: Jaspard, Polus et Cie, 1963.

- Getty 1965

- Getty, J. Paul. The Joys of Collecting. New York: Hawthorn Books, 1965.

- Getty 1956

- Getty, J. Paul. “Vingt mille lieues dans les musées.” Connaissance des Arts 57 (November 1956): 76–81.

- Hoffman 1975

- Hoffmann, Edith. “Louis XV—in Paris.” Burlington Magazine 117, no. 864 (March 1975): 188–190.

- Jackson-Stops 1985

- Jackson-Stops, Gervase, ed. The Treasure Houses of Britain: Five Hundred Years of Private Patronage and Art Collecting. Washington, DC, and New Haven, CT: National Gallery of Art and Yale University Press, 1985.

- Kjellberg 1989

- Kjellberg, Pierre. Le mobilier français du XVIIIe siècle: Dictionnaire des ébénistes et des menuisiers. Paris: Éditions de l’Amateur, 1989.

- Locatelli, Lavier, and Pousset 2011

- Locatelli C., C. Lavier, and D. Pousset. “Synopsis des chantiers de bois de la cathédrale d’Auxerre depuis 1235.” In Saint-Étienne d’Auxerre, la seconde vie d’une cathédrale (Auxerre Symposium 27–28 Sept. 2007), 177–81. Auxerre: CEM and Éditions Picard, 2011.

- Louis XV . . . 1974

- Louis XV, un moment de perfection de l’art français. Exh. cat. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1974.

- Meyer and Arizzoli-Clémentel 2002

- Meyer, Daniel, and Pierre Arizzoli-Clémentel. Versailles: Furniture of the Royal Palace: 17th and 18th Centuries. 2 vols. Dijon: Éditions Faton, 2002.

- Musée national Magnin 1992

- Musée national Magnin: Trois ans de restorations, 1989–1992: Hôtel Lantin, Dijon, 23 juin. Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1992.

- Pradère 1989a

- Pradère, Alexandre. French Furniture Makers: The Art of the Ébéniste from Louis XIV to the Revolution. Malibu, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1989.

- Pruchnicki 2013

- Pruchnicki, Vincent. Arnouville: Le château des Machault au XVIIIe siècle. Paris: Éditions Lelivredart, 2013.

- Ramond 2000a

- Ramond, Pierre. Masterpieces of Marquetry. Vol. 2, From the Régence to the Present Day. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2000. Originally published as Chefs-d’oeuvre des marqueteurs. Vol. 2, De la Régence à nos jours. Dourdan: Éditions H. Vial, 1996.

- Stephen and Lee 1973

- Stephen, Leslie, and Sidney Lee, eds. The Dictionary of National Biography: From the Earliest Times to 1900. Vol. 8, Glover-Harriott. Reprint. London: Oxford University Press, [1900] 1973.

- Verlet 1991

- Verlet, Pierre. French Furniture of the Eighteenth Century. Translated by Penelope Hunter-Stiebel. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1991.

- Verlet 1982

- Verlet, Pierre. Les meubles français du XVIIIe siècle. 3rd ed. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1982.

- Wescher 1955

- Wescher, Paul. “French Furniture of the Eighteenth Century in the J. Paul Getty Museum.” Art Quarterly 18, no. 2 (Summer 1955): 115–35.

- Wilson and Hess 2001

- Wilson, Gillian, and Catherine Hess. Summary Catalogue of European Decorative Arts in the J. Paul Getty Museum. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2001.

- Wilson 1975

- Wilson, Gillian. “The J. Paul Getty Museum: 6ème partie: Les meubles baroques.” Connaissance des Arts 279 (May 1975): 107–13.

- Works of Art from the Widener Collection 1942

- Works of Art from the Widener Collection. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, 1942.