6. Commode

- French (Paris), ca. 1740

- By Bernard II van Risenburgh (French, after 1696–ca. 1766, master before 1730)

- White oak, set with panels of Chinese red lacquer on a coniferous substrate, and sycamore maple* painted with European lacquer; gilt bronze mounts; brass and iron hardware and lock; brèche d’Alep top

- H: 2 ft. 9 in., W: 3 ft. 9 in., D: 1 ft. 9 1/2 in. (83.8 × 114.3 × 54.9 cm)

- 72.DA.46

Description

The rectangular commode, decorated with gilt bronze mounts, has splayed convex sides, a convex front, and a serpentine lower profile. It is supported on four cabriole legs of five-sided section. It contains two drawers that possess keyholes but no mechanics or lock boxes. There is no visible horizontal division between the drawer fronts, the lower of which carries the apron. The top of brèche d’Alep is shaped to conform to the top of the commode, and it has a molded edge.

Each front corner is set with a pierced corner mount that consists of two parts. The upper section is composed of a pierced cartouche, the frame of which is stippled and set with C-scrolls. Above is a central rosette flanked by flame motifs, and below the scrolls are set with guilloche studded with cabochons. These lower scrolls flank a convex shell-like motif that terminates in a leafy pendant. This element is set over the shoulders of the lower section of the mount, which is also pierced. Its stippled frame is set with flame and leaf motifs, the latter clasping the winged extensions and forming a terminating pendant. A plain ribbed molding extends down the outer edge of the leg to the foot.

The two drawers are framed by a complex mount cast in a number of sections. Above, a simple undulating strip mount is set with a twisting leafy vine that carries berries. It is set at the center with a pierced escutcheon composed of three leaf-bordered C-scrolls enclosing an arrangement of five feathers. These rise from a pierced and ribbed cabochon, supported by apposed C-scrolls that flank the keyhole. The escutcheon terminates below in a pendant of three leaves and a bud.

The upper corners of the framing mount are occupied by two rising and joined C-scrolls, which are bordered on their outer edges with flame motifs and by smaller C-scrolls on their inner edges. At the junction of the scrolls a double cup of leaves containing berries rises from a small cabochon, while a pendant of three leaves and a bud hang below. Each side of the framing mount consists of a simple undulating strip mount set with a leafy vine with berries. This rises from a similarly entwined short section of pierced guilloche that emerges from a curved composition of leaves. This forms the lower corner of the frame and is set on the outside with a short leafy branch with berries that curves down toward the juncture of the legs and the body of the commode.

The lower part of the framing mount is likewise composed of a simple flat molding entwined with a leafy vine that emerges from a scroll formed by the aforementioned cluster of leaves. These moldings are attached to two C-scrolls set above the central apron mount. The latter is centered by a trilobed shell-like form, set with alternating large and small oval cabochons. To either side extend stippled strips that are curved to follow the profile of the apron. They have raised borders and are set with a flamelike motif. Each is clasped below by a short leafy branch that emerges from a corolla and terminates in a scroll of leaves.

The keyhole escutcheon on the lower drawer front, a nineteenth- or twentieth-century replacement (See “Technical Description” below), consists of five feathers supported by two C-scrolls and is of the same form as these elements forming the escutcheon above, centering the upper frame. The framing mounts of the sides of the commode are of the same model as that on the front of the piece, with the central section (containing the keyhole escutcheon and the apron mount) removed and the simple flat strip mounts joined. The feet are mounted with gilt bronze sabots that adopt many of the same design features of the commode’s other mounts. Each features five feathers bounded by C-scrolls.

The fronts of the drawers are set with a large panel of Chinese red lacquer with illustrations in gold, brown, and black. The scene of an emperor and his court is visually centered by a short staircase painted above the apron. It leads to an open terrace surrounded by a low framed and paneled wall. A large central screen is painted with mountains, groups of trees, and swirling clouds above. In front of the screen is a group of five figures: the central seated and bearded emperor, flanked by two female and two male courtiers. To the left a group of seven courtiers stand in a loose arrangement, looking in various directions. On the right a group of five courtiers stand similarly posed. One man stands on the carpet, with his back toward the viewer; another, near the top of the flight of steps, is also turned to face the seated emperor. Short leafy plants rise here and there, both inside and outside the walled area, while a crane carrying a ribbon-tied double scroll in its beak flies from the left toward the central group.

The left side of the commode is set with a panel of Chinese red lacquer, depicting in gold and brown a low-lying building set on a rocky shore. Waves and promontories are painted in the foreground. Behind the building are trees of several species and bushes. Three birds fly in the sky. The right side of the commode is also set with a panel of Chinese red lacquer painted gold and brown (fig. 6-1). At its center is a house on stilts over water with a bridge extending from it. In the foreground are waves, promontories, and small plants. A tree rises behind the house, and a branch of a fir tree extends into the scene from the left. Two birds fly in the sky, which also contains clouds. The remaining surfaces of the commode have European red lacquer applied in a hue that matches the ground of the Chinese lacquer.

Marks

The commode is stamped “B.V.R.B.” on the top of both the left and right rear leg stiles, and each of these stamps in flanked on either side by a “JME” mark, for jurande des menuisiers-ébénistes (fig. 6-2).

Figure 6-2

Figure 6-2Commentary

The commode is stamped “B.V.R.B.,” for Bernard II van Risenburgh.1 A number of commodes of this design and size, with gilt bronze mounts of the same model, exist. Unless noted otherwise, they all bear Van Risenburgh’s stamp.

a) Musée des Beaux-Arts de Caen. A commode of the same model and mounts, with the exception of the keyhole escutcheon on the lower drawer. It is veneered with panels of Chinese black and gold painted lacquer showing pagodas, trees, and bridges (fig. 6-3).2

b) Victoria and Albert Museum, London. A commode of the same model and mounts, with the exception of the lower keyhole escutcheon, which resembles that on the Caen commode. An added arrangement of gilt bronze is found above the center of the lower part of the framing mount. It is veneered with panels of black and gold Japanese lacquer, painted with mountains, landscapes, trees, pagodas, and water.3

c) Sold at Christie’s, Monaco, June 16, 2001, no. 714. A commode of the same model and mounts, with the exception of the lower keyhole escutcheon, which resembles that on (a) and (b) above. It is veneered with panels of black and gold Chinese lacquer showing a bridge, trees, two women, and a child.4

d) Partridge Fine Arts, London. Summer exhibition, 1984, no. 23. A commode of the same model and mounts, with the exception of the lower keyhole escutcheon and the apron mount. The latter is a replacement as the profile of the original mount can still be seen on the apron. It is veneered with panels of black and gold Japanese lacquer showing mountainous landscapes and trees.5

e) Sold, Artcurial, Paris, December 13, 2005, lot 119, from the collection of Jean Rossignol and now in the collection of the Musée du Domaine départemental de Sceaux. A commode of the same model and mounts, with the exception of the lower section of the corner mounts and the feet mounts. The front, sides, and top are veneered with panels of Coromandel lacquer showing buildings, trees, rocky escarpments, and a bridge peopled with numerous figures. It is not stamped “B.V.R.B.” but bears the mark of the château of Sceaux.6

f) Sold, Palais Galliéra, Paris, June 18 and 19, 1964, lot 184. A commode of the same model and mounts, with the exception of those at the corners and feet. Veneered with wood marquetry of large scrolls on a pale striped ground. Stamped “DELORME” for Adrien Faizelot-Delorme (master 1748, died after 1783).7

g) Sold, Christie’s, New York, May 21, 1996, lot 323. A commode of the same model and mounts, with the exception of the mounts at the feet. Veneered with tulipwood and amaranth with end cut marquetry. The commode had been previously sold at Christies, New York, in 1994 (October 26, lot 87), and in 1982 at Sotheby’s, Monaco (November 6, no. 186).8

Figure 6-3

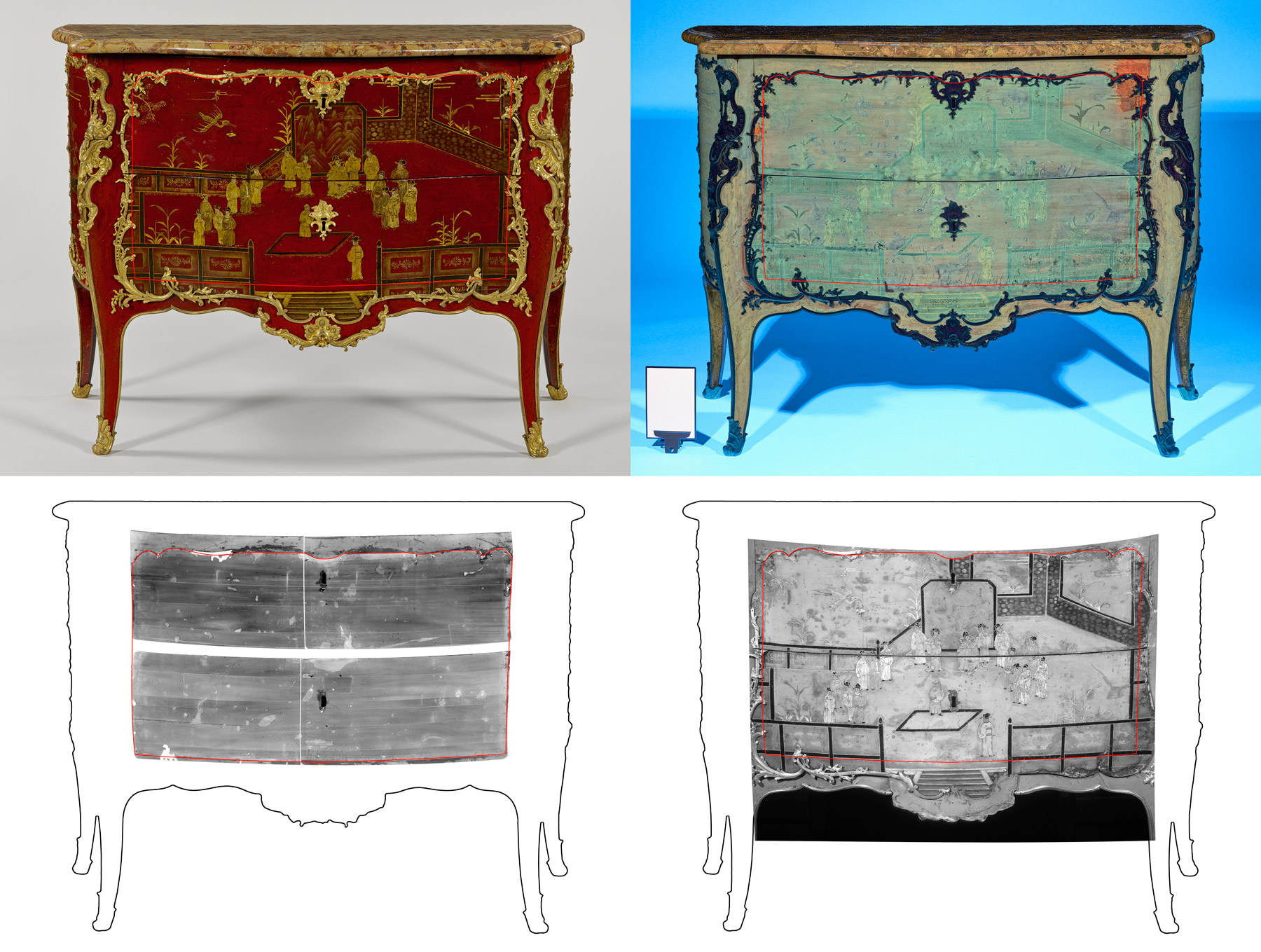

Figure 6-3Four other commodes of this model, similarly mounted but painted with red and gold European lacquer, exist.9 And only one, also similarly mounted, stamped “B.V.R.B.” and “JME” on the left strut, is decorated, like the Museum’s commode, with Chinese red lacquer. It was probably the one delivered by Lazare Duvaux to Marchioness d’Haussy in 1756 (fig. 6-4).10 All of them show the same scene of numerous figures robed in gold standing on an open-air terrace surrounded by low screens as found on the Museum’s commode. But the Museum’s commode is the only one that has a figure in the foreground to the right. Consequently, the painter who did the first European lacquer commode copied the scene after the Chinese lacquer commode now at the Louvre Abu Dhabi and not the Museum’s commode, and he or the other painters then followed suit. One, who painted the commode now in the musée des Beaux-Arts, Dijon, could not resist the use of European vanishing perspective when depicting the central carpet.11 The fact that two nearly identical large panels of Chinese lacquer, with only one figure distinguishing one from the other, were used to make two very similar commodes is a good example of the production of multiples that China did for lacquer export. An X-ray of the Museum’s commode reveals that the panel of Chinese lacquer only extends to just above the portrayal of the central staircase. This addition to the scene is painted in European lacquer, and the steps are therefore drawn in European perspective (See “Technical Description” below).

Figure 6-4

Figure 6-4By the early 1750s, when the marchand-mercier Thomas Joachim Hébert had retired from business, Van Risenburgh was working primarily for Lazare Duvaux. In this marchand-mercier’s surviving journals for the years 1748 to 1758 the following commodes are listed:

[May 1754] M. Dufour, le père: Une commode de vernis rouge à pagodes, ornée partout en bronze doré d’or moulu, le marbre de vert campan, 720 l.12

[ . . . ]

[June 1754] Mme la Duchesse de Mirepoix: une commode plaquée en vernis rouge à pagodes, garnie partout en bronze doré d’or moulu, avec son marbre de vert campan de trois pieds & demi, 720 l.13

[ . . . ]

[October 1756] Mme la Marq. d’Haussy: une commode de vernis la Chine, en rouge à pagodes, garnie partout en bronze doré d’or moulu, avec son marbre de vert campan de trois pieds & demi, 720 l.14

[ . . . ]

[December 1756] S. A. S. Mgr le Duc d’Orléans: une commode de lacq rouge, garnie partout en bronze doré d’or moulu, le marbre d’Alep, 720 l.15

[ . . . ]

[March 1758] M. Duperron: une commode de vernis rouge, garnie partout de bronze doré d’or moulu, avec son marbre de vert campan de trois pieds & demi, 720 l.16

These five commodes all cost the same and are similarly described. It is very likely that they are the ones that are known today. All had marble tops of vert campan, except for the single lacquered example sold to the duc d’Orléans, which is described as having a top of brèche d’Alep. The Museum’s commode is topped with this stone, and it is therefore possible that it is the one made for Orléans. It is of interest to note that the first three of the five red lacquer commodes to be purchased from Lazare Duvaux were in European red lacquer, which may have been more popular in its pristine condition than the older genuine Chinese lacquer.

Provenance

–1972: Private Collection (Paris, France) [sold, Objets d’art et d’ameublement principalement du XVIIIe siècle, Palais Galliéra, Paris, March 2, 1972, lot 109, through French and Company to the J. Paul Getty Museum].17

Exhibition History

Imagining the Orient, J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Center (Los Angeles), October 5, 2004–April 3, 2005.

Bibliography

, 282, fig. 3; , 139; , 26, no. 26; , 188–89, fig. 85; , 15, no. 26; , vol. 2, 1100–1103, 1105, figs. 1–2, 4–5; , 156 n. 3 (T. Wolvesperges).

- G.W.

Technical Description

The substrate of the commode is constructed primarily of white oak and is an example of very neat and precise cabinetmaking. The nature of the construction suggests a certain order of assembly. First the front and rear legs on each side would have been attached to the case sides. Each of the four leg posts runs from the top of the case to the floor and is made of two long boards laminated together to form a solid square block from which the final curved form was shaped. In the rear, the laminates of the rear posts are each approximately 3 cm x 6 cm and are arranged front and back, while in the front, the laminates are each approximately 4 cm x 8 cm in section and are arranged side to side (fig. 6-5). The sides of the case are made of three or four butt-joined boards, with the grain running horizontally, which were attached to the front and rear posts with long tongue-and-groove joints.

Figure 6-5

Figure 6-5Next, the back panel, comprising a tripartite frame-and-panel construction, would have been fitted to the rear legs. The lower rail would have been inserted first, attached with unpinned mortise-and-tenon joints (none of the mortise-and-tenon joints in this commode are pinned) (fig. 6-6). The two upright medial stiles were then attached to the lower rail of the case back, also using unpinned mortise-and-tenon joints, and the raised panels—flat on the inside and raised with a cove molding on the exterior—were placed in grooves in the posts and framing members. The simple quarter-round cove molding on the edges of all the panels in this commode is unusual, being found in only one other entry in this catalogue, cat. no. 8, the double desk by Van Risenburgh. The upper rail, mortised to receive the medial stiles, was then slid into place from above, which explains the unusual unpinned slip joints (single-shouldered, open, mortise-and-tenon joints) used to attach the rail to the legs at either end (fig. 6.7). At this stage, the upper rail would have been left unglued for reasons explained below.

The next element to be added would have been the case bottom. The lower rail of the back is grooved along its bottom interior edge and serves as a rear rail for the case bottom. The side rails of the case bottom are attached to the back rail with a tongue-and-groove joint, while at the front, the only attachment is a very small tongue that fits into the groove at the very end of the front rail. There is no attachment between the rails and the leg posts, and likewise there is no attachment between the rails and the case sides.

The case bottom’s front rail was then inserted from the front, attached to the legs with sliding dovetail joints. These joints were subsequently covered by veneer. Separate pieces of oak were glued to the bottom of the front edge of the rail on each side, adding the depth needed to create the curved profile of the skirt (fig. 6-8).

Figure 6-8

Figure 6-8The dustboard, or middle panel assembly, was then incorporated into the structure in a manner similar to that of the lower panel, with one notable exception. Here, the rear rail is attached to the back legs with simple tongue-and-dado joints; the dadoes are cut into the leg, at the full thickness of the rail, from front to back. Given that the case back construction was already in place, the back rail would have been the first piece inserted, followed by the four front-to-rear rails (mortise and tenoned at front and back) and the three raised panels, with cove-molded edges facing up. Finally, the front rail would have been inserted, again from the front. The sliding dovetail for this joint clearly runs through to the front of the front leg and is covered by veneer.

The top panel assembly was the last section to have been added. The two medial rails are through-tenoned into the top, rear rail (fig. 6-9). The side rails are dovetailed into the legs at the front and back with single open-faced dovetails. Notably, these have been positioned so that they hide the grooves cut into the legs for the side panels. These grooves were cut along the entire length of the inside faces of both the front and rear legs, presumably while the wood was still square in cross section. Below the level of the case bottom, much of the grooving was cut away when the leg was shaped and some was covered by apron blocks or veneer, but, especially at the rear, the grooves are still clearly visible (fig. 6-10). At the top of the leg, the end of the groove for the back panels is also exposed; however, a small patch of wood has been inserted to fill the gap, adjacent to the tenon for the rear rail (see fig. 6-5). Similar gaps in the top of the legs of Van Risenburgh’s commode à vantaux (cat. no. 5) either have been left open or the patches have fallen out.

Figure 6-9

Figure 6-9 Figure 6-10

Figure 6-10In addition to the dovetails, the side rails of the case top are also tongue and grooved into the top rail of the back panel, utilizing the same groove used for the top panels. In order for this to be accomplished, the top rear rail of the back must have been lifted up enough to expose the groove along its top edge. The rails and panels of the top would then have been fitted together and the entire top assembly then lowered into place and glued.

The construction of this commode is virtually identical to that of the Van Risenburgh commode with Chinese red lacquer at the Louvre Abu Dhabi described in “Commentary” above (fig. 6-4), with the exception that the majority of mortise-and-tenon joints and slip joints in the related commode are pinned.

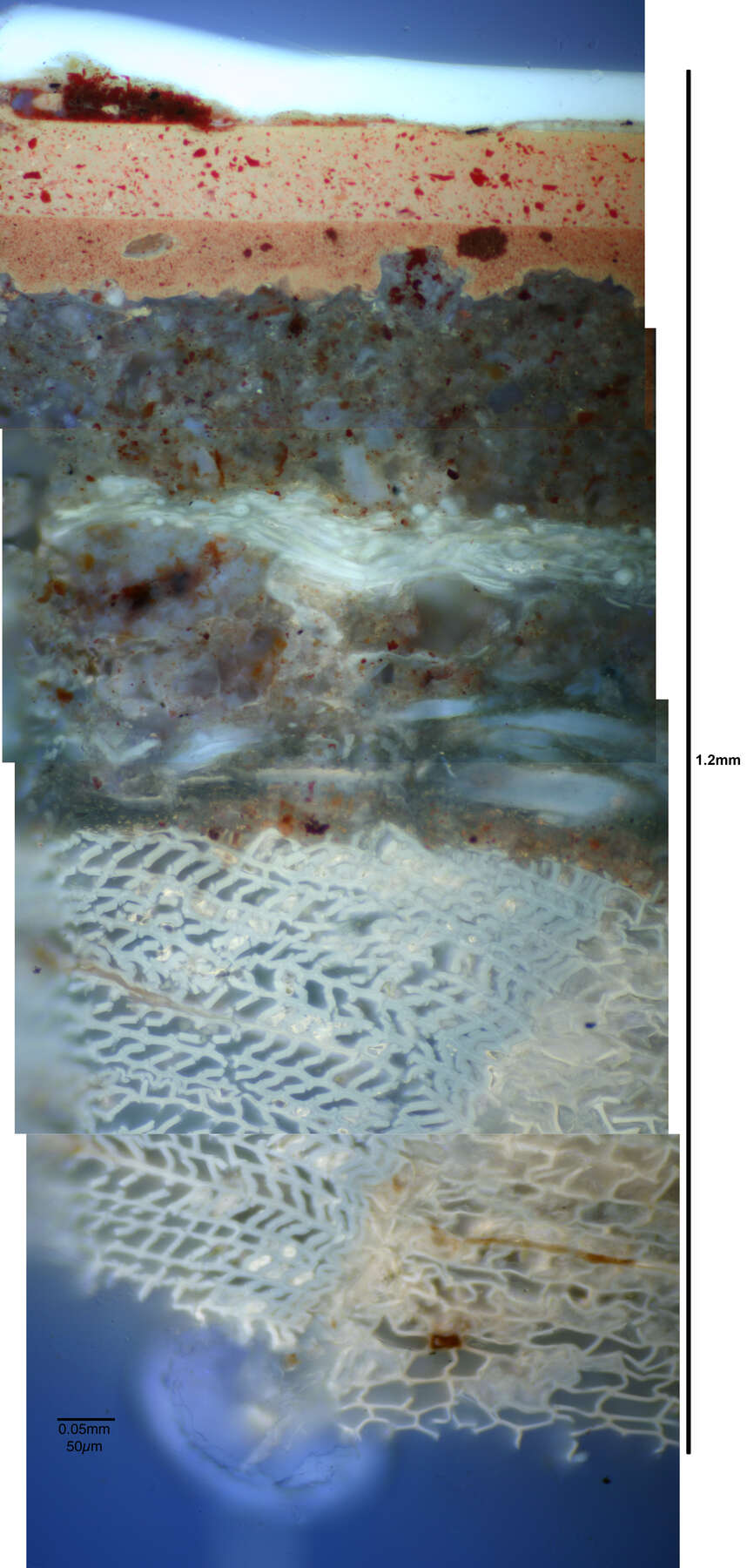

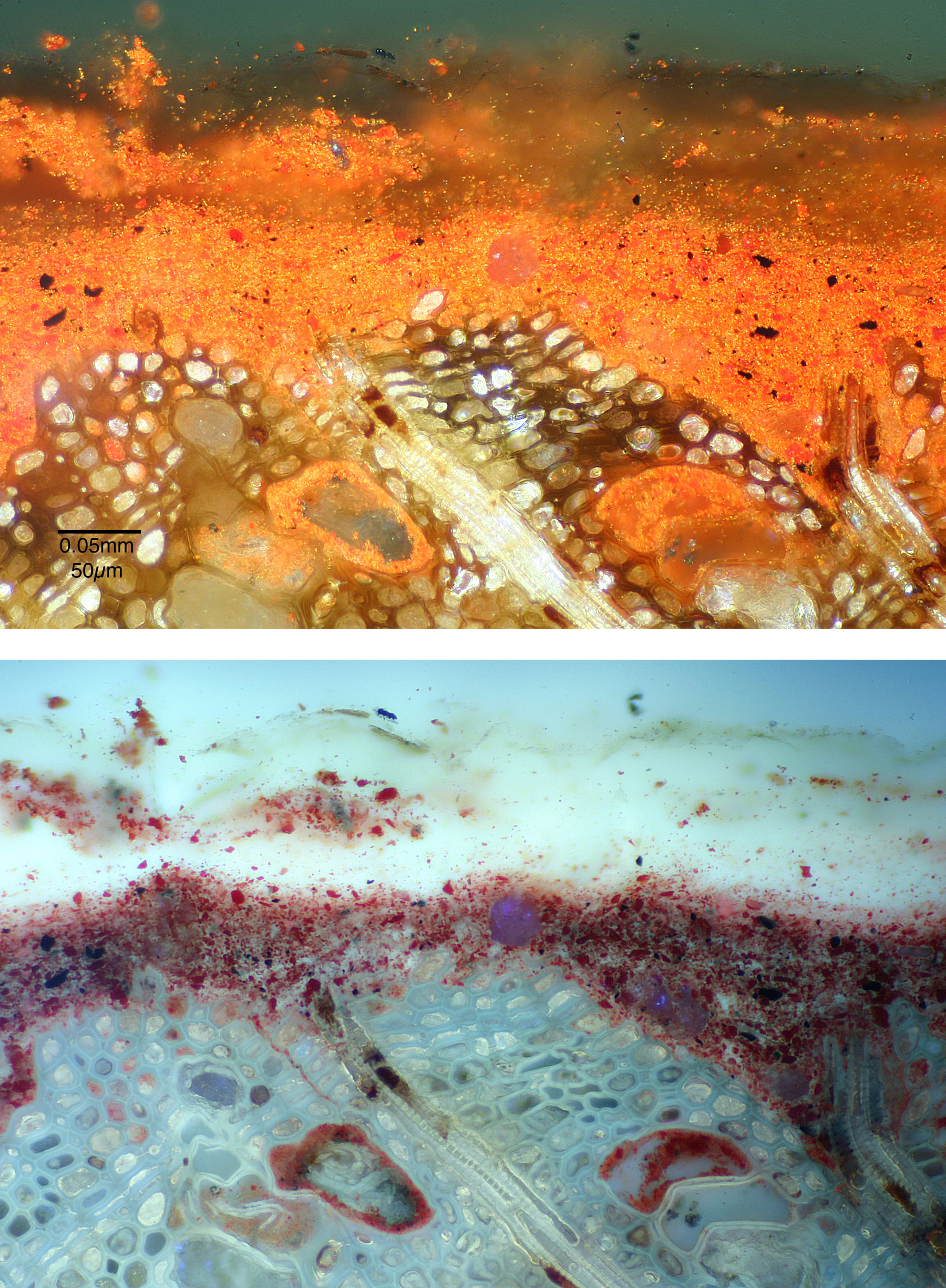

The surface of the commode has been veneered with panels of Chinese red lacquer supplemented by European lacquer on the legs and edges. When examined using X-radiography and infrared reflectography, the Chinese red lacquer panels on the front of the drawers appear to be from a single large panel of lacquer, not reassembled from sections of a folding screen as is more commonly encountered (see cat. no. 13). The original form and function of such a wide panel of red lacquer is not evident, but it is possible that such panels were taken from chests, tabletops, or even produced specifically for export to be used as ornaments in European architecture or furniture. Black lacquer panels of similar format may be found in the so-called Red Room of the Chinese Pavilion of Drottningholm Palace in Stockholm. The Chinese red lacquer panels on this commode have been cut down to approximately 1 to 1.3 mm in thickness, leaving just a very thin layer of the original conifer wood substrate in place (fig. 6-11). This veneer of lacquer then was applied to the case and to the drawer fronts, presumably using traditional veneering techniques. The panels that adorn the drawer fronts and two sides of the commode have a layer structure typical of Chinese export lacquer and similar to that of the Chinese lacquer panels used on the Dubois secrétaire (cat. no. 13). First, two clay-containing foundation layers, bound with a mixture of drying oil and blood, were applied to the wooden substrate. Markers for cedar oil and gum benzoin were also detected in the foundation layers. While cedar oil has been detected in other examples of Chinese export lacquer, gum benzoin is not typically reported in these objects.18 This foundation also contains an interlayer of paper between the two applications of the coarse foundation mixture. The foundation was then coated with two layers of laccol-based Asian lacquer both of which contain cedar oil, laccol carbohydrates, and tannins. The lower lacquer layer is pigmented with red iron earth and the upper with the brighter, more expensive vermilion.

Figure 6-11

Figure 6-11As mentioned in “Commentary” above, the Chinese panels, which cover most of the commode’s surface, do not extend to the top of the upper drawer or the bottom edge of the lower drawer front. Here, a French craftsman added European imitation lacquer to extend the composition, including, at the bottom, the set of stairs in Western perspective. In X-radiography and infrared photography, the top and the bottom of the Chinese lacquer panel are readily apparent (fig. 6-12).

Figure 6-12

Figure 6-12Around the Chinese lacquer panels, the entire case has been veneered with sycamore maple applied with the grain running diagonally on both sides and on the front legs. This veneering is much smoother and more fine-grained than the oak substrate, creating a surface that is more amenable to a high polish lacquer imitation and requires less grain filling than oak would. On the top corners of the front leg posts, large blocks of solid sycamore maple have been spliced into the oak substrate (fig. 6-13). This has been done because this area is visible behind the pieced corner mounts and thus needed to be given a coat of European red lacquer. Normally this would require the area to be veneered with smooth-grained domestic wood first; however, as veneering around a very tight curve would be difficult, this entire corner block has been cut out and a piece of solid, smooth sycamore maple inserted.

Figure 6-13

Figure 6-13The European lacquer was built up in a series of spirit-resin varnish layers applied to the areas surrounding the Asian lacquer panels as well as the legs (fig. 6-14). First, a pigmented varnish was applied directly to the sycamore maple veneer. This layer appears deep within the wood grain when examined in cross section at high magnification (fig. 6-15). Based on additional analysis with scanning electron microscopy with energy dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) and pyrolysis gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (py/GC-MS), the layer was colored with vermilion and bound in a sandarac-spirit varnish, likely with the addition of gum elemi and camphor. These materials are in keeping with a fine eighteenth-century “white varnish.”19 In the eighteenth century, sandarac was the most common major ingredient for transparent gloss lacquers. The resin readily dissolved in alcohol and dried quickly. It was also one of the lightest-colored resins available at the time and hard enough to take a high polish.20 The softer resins gum elemi and camphor would have been added to compensate for the brittleness of the sandarac and to plasticize the resin film, improving the toughness and adhesion of the lacquer.21 For European red lacquer, spirit-resin varnishes were the predominant recipes listed in period literature; drying oil-resin and essential oil varnishes were rarely mentioned.22 While some period recipes for red lacquer call for the use of shellac and colophony, there does not appear to be any evidence that either of these materials were used in the original European lacquer on the commode, with the exception of the later restoration coatings carried out, at least in part, with bleached shellac. The presence of bleached shellac, developed in the early nineteenth century, can be detected analytically by the identification of specific chlorinated resin compounds.

Figure 6-14

Figure 6-14 Figure 6-15

Figure 6-15In general, the gilt bronze mounts on the commode appear to be original, finely chased, and in good condition. Twenty brass elements from the commode were analyzed by X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (XRF) for alloy composition. The results for eighteen of the twenty measurements were consistent with eighteenth-century manufacture. The escutcheon of the lower drawer appears to be a late nineteenth- or twentieth-century replacement, as does one small section of foliate molding from the top drawer. These two elements contain elevated levels of zinc and extremely low levels of impurities such as silver, antimony, and iron, making it highly unlikely that they date to the eighteenth century.

The marble top is made from brèche d’Alep from the Bouches-du-Rhône, France. The multicolored breccia marble is somewhat unusual for its very small (< 5 cm) cobbles. Normally brèche d’Alep contains large cobbles up to 30 cm in length. The predominant color of the cobbles is a tan-cream, although red and even black cobbles are present.

- A.H.,

- J.C.,

- K.P.,

- M.S.,

- and R.S.

Notes

For more information on Bernard II van Risenburgh, see primarily , 183–99; , 56–63. See also Daniel Alcouffe, in , 323–24. ↩︎

85 x 114 x 56 cm; , 57; , 124. ↩︎

83.3 x 115.2 x 53.3 cm; Jones Collection, acc. no. 1094-1882. , 102–3. ↩︎

H: 2 ft. 8 in., W: 3 ft. 9 in., D: 1 ft. 8 7/8 in. (81.5 x.114.5 x 53 cm); sold, Christie’s, Important Mobilier, Orfèvrerie et Objets d’art dont une collection provenant d’une villa du Cap Ferrat, June 16, 2001 (Monaco: Christie’s, 2001), lot 714. ↩︎

H: 2 ft. 9 in., W: 3 ft. 8 1/2 in., D: 1 ft. 9 in. (84 x 113 x 53 cm); Partridge Fine Arts Ltd., Summer Exhibition 1984, June 4–July 28, 1984 (London: Partridge Fine Arts Ltd., 1984), no. 23. ↩︎

82.5 x 125.5 x 54 cm; Artcurial, Collection Jean Rossignol, tableaux anciens, objets d’art et bel ameublement du XVIIIe siècle, December 13, 2005 (Paris: Artcurial, 2005), lot 119, inv. no. 2005.14.1; , 134–35, no. 32 (Y. Bapt). ↩︎

82.5 x 119 x 50.5 cm; Palais Galliéra, Tableaux anciens, objets d’art et de bel ameublement du XVIIIe siècle, June 18 and 19, 1964 (Paris: Palais Galliéra, 1964), lot 184. See also , 180, fig. 164. ↩︎

H: 2 ft. 10 1/4 in., W: 3 ft. 8 1/2 in., D: 1 ft. 9 1/4 in. (87 x 112.5 x 54 cm); Christie’s, Important French Furniture from a Private Collection, May 21, 1996 (New York: Christie’s, 1996), lot 323; Christie’s, Important French Furniture, Objects of Art and Sculpture, October 26, 1994 (New York: Christie’s, 1994), lot 87; Sotheby’s, Important French Furniture, Decorations, and Clocks, November 6, 1982 (New York: Sotheby’s, 1982), lot 186. See also , 190, fig. 176. ↩︎

1) Musée des Beaux-Arts, Dijon, from the Collection Trimolet. See , 169, fig. 3. The European lacquer decoration on the front of the commode differs in some respects from that on the Museum’s example. The carpet in the middle ground is shown in true perspective, and the low screen below it extends beyond the confines of the lower gilt bronze frame to cover the area of the apron. The flying crane does not carry a ribbon-bound double scroll in its beak.

2 and 3) Sold, Sotheby’s, Bel ameublement: Collection de M. et Mme Delplace, ancienne collection René Weiller et divers amateurs, June 15, 1996 (Monaco: Sotheby’s, 1996), lots 132 and 133, a pair, formerly in the collection of the duc de la Rochefoucauld-Doudeauville. They are painted with European lacquer, and in both examples the painted decoration extends beyond the lower framing mount over the surface of the apron. These commodes are now in a private New York collection. They are also illustrated in , pl. 31.

4) Another example is reputed to be in a private collection in Le Mans, France. ↩︎

Now in the collection of Louvre Abu Dhabi. H: 33 in., L: 45 3/4 in., D: 21 1/2 in. (84 x 116 x 54.5 cm). I thank Alexis and Nicolas Kugel for this information and the photograph of the commode. ↩︎

, 200, no. 1771. ↩︎

, 205, no. 1814. ↩︎

, 298, no. 2606. ↩︎

, 305, no. 2675. ↩︎

, 353, no. 3061. ↩︎

French and Company invoice, March 16, 1972, in the files of the Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

; ; . ↩︎

For instance, , 33–34, describes a recipe of Father Zahn that calls for “ten ounces of wine spirit, two ounces of sandarac, and two of common Terebentine or Venice; the latter is best.” also discusses the use of gum elemi and camphor in many sections. ↩︎

, 28. ↩︎

, 105; , 55. ↩︎

, 134. ↩︎

Bibliography

- 18th Century: Birth of Design 2014

- 18th Century: Birth of Design: Furniture Masterpieces 1650–1790. Exh. cat. Paris: Éditions Faton, 2014.

- Alcouffe 1988

- Alcouffe, Daniel. “La commode du Cabinet de retraite de Marie Leczinska à Fontainebleau entre au Louvre.” La Revue du Louvre et des Musées de France 38, no. 4 (1988): 281–84.

- Baroli 1957

- Baroli, Jean-Pierre. “Le mystérieux B.V.R.B. enfin identifié.” Connaissance des Arts 61 (March 1957): 56–63.

- Bonanni 1723

- Bonanni, Filippo. A treatise on varnishes, where one gives the manner of composing one which resembles perfectly that of China, and several others which concern painting, gilding, etching, &c. Translated by Antoine-Joseph Dezallier and Charles-François de Cisternay Dufay. Paris: L. d’Houry, 1723.

- Boutemy 1957

- Boutemy, André. “BVRB et la morphologie de son style.” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 49 (May 1957): 165–74.

- Bremer-David et al. 1993

- Bremer-David, Charissa, et al. Decorative Arts: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue of the Collections of the J. Paul Getty Museum. Malibu, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1993.

- Duvaux 1873

- Duvaux, Lazare. Livre-journal de Lazare Duvaux, Marchand-Bijoutier ordinaire du Roy 1748–1758, vol. 2. Edited by Louis Courajod. Paris: Lahure, 1873.

- Heginbotham et al. 2008

- Heginbotham, Arlen, Herant Khanjian, Rachel Rivenc, and Michael Schilling. “A Procedure for the Efficient and Simultaneous Analysis of Asian and European Lacquers in Furniture of Mixed Origin.” In ICOM-CC 15th Triennial Conference New Delhi, India Preprints, edited by Janet Bridgeland, 2 (2008): 608–16.

- Heginbotham et al. 2016

- Heginbotham, Arlen, Julie Chang, Herant Khanjian, and Michael R. Schilling. “Some Observations on the Composition of Chinese Lacquer.” Studies in Conservation 61, suppl. 3 (2016): S28–S37. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00393630.2016.1230979.

- Kjellberg 1989

- Kjellberg, Pierre. Le mobilier français du XVIIIe siècle: Dictionnaire des ébénistes et des menuisiers. Paris: Éditions de l’Amateur, 1989.

- Koller and Baumer 1997

- Koller, Johann, and Ursula Baumer. “Baroque and Rococo Transparent Gloss Lacquers: The Scientific Study of Lacquer Systems.” In Baroque and Rococo Lacquers, edited by Katharine Walch and Johann Koller, 52–84. Munich: Bayerisches Landesamt für Denkmalpflege, 1997.

- Louis XV . . . 1974

- Louis XV, un moment de perfection de l’art français. Exh. cat. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1974.

- Matsen, Petisca, and Auffret 2017

- Matsen, Catherine, Maria João Petisca, and Stéphanie Auffret. “When Science Reveals Craft Practices: Recent Findings in the Py-GC/MS Analysis of Chinese Export Lacquer.” In ICOM-CC 18th Triennial Conference Preprints: “Linking Past and Future,” Copenhagen, 4–8 September 2017. Copenhagen: ICOM-CC, 2017.

- Musée des beaux-arts et collection Mancel, Caen 1984

- Musée des beaux-arts et collection Mancel, Caen. Caen: Musée des beaux-arts, 1984.

- Petisca et al. 2011

- Petisca, Maria João, José Frade, Margarida Cavaco, Isabel Ribeiro, Antónió José Candeias, José Graça, and José Carlos Rodrigues. “Chinese Export Lacquerware: Characterization of a Group of Canton Lacquer Pieces from the 18th and 19th Centuries.” In ICOM-CC 16th Triennial Conference, Lisbon, 19–23 September 2011: Preprints, edited by Janet Bridgeland, 10. Lisbon, Portugal: Critério-Produção Grafica, 2011.

- Pradère 1989a

- Pradère, Alexandre. French Furniture Makers: The Art of the Ébéniste from Louis XIV to the Revolution. Malibu, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1989.

- Tapié 1994

- Tapié, Alain. Le musée des beaux-arts de Caen. Paris: Fondation Paribas, 1994.

- Vacquier 1910

- Vacquier, Jules. Les vieux hôtels de Paris. Vol. 1, ser. 3. Paris: F. Contet, 1910.

- Walch 1997

- Walch, Katharina. “Baroque and Rococo Transparent Gloss Lacquers: I. The Replication of White Lacquers on the Basis of Historic Sources and Scientific Examination” and “Baroque and Rococo Red Lacquers: The Red Lacquer-work in the Miniaturenkabinett of the Munich Residenz. Replicating the Technique on the Basis of Historic Sources and Scientific Inverstigation.” In Lacke des Barock und Rokoko = Baroque and Rococo Lacquers, edited by Katharine Walch and Johann Koller, 21–52 and 129–44. Munich: Bayerisches Landesamt für Denkmalpflege, 1997.

- Watin 1773

- Watin, Jean-Félix. L’art du peintre, doreur, vernisseur: Ouvrage utile aux artistes & aux amateurs qui veulent entreprendre de peindre dorer & vernir toutes sortes de sujets en bâtimens, meubles, bijoux, equipages, &c. 2nd rev. ed. Paris: Grangé, 1773.

- Webb 2000

- Webb, Marianne. Lacquer Technology and Conservation: A Comprehensive Guide to the Technology and Conservation of Both Asian and European Lacquer. Butterworth-Heinemann Series in Conservation and Museology. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2000.

- Wilk 1996

- Wilk, Christopher, ed. Western Furniture, 1350 to the Present Day in the Victoria and Albert Museum London. London: Philip Wilson, 1996.

- Wilson and Hess 2001

- Wilson, Gillian, and Catherine Hess. Summary Catalogue of European Decorative Arts in the J. Paul Getty Museum. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2001.

- Wolvesperges 2000

- Wolvesperges, Thibaut. Le meuble français en laque au XVIIIe siècle. Paris: Éditions de l’Amateur, 2000.