4. Pair of corner cupboards

- French (Paris), ca. 1740

- By Bernard II van Risenburgh (French, after 1696–ca. 1766, master before 1730)

- White oak* veneered with amaranth*, cherry*, and sycamore maple*, set with panels of black Japanese lacquer on Japanese arborvitae*, and painted with European lacquer; gilt bronze mounts; brass and iron hardware and lock; sarrancolin marble tops

- H: 3 ft. 3 1/8 in., W: 2 ft. 10 3/4 in., D: 2 ft. 1/8 in. (99.4 × 88.3 × 61.3 cm)

- 72.DA.44.1–.2

Description

Each rectangular corner cupboard has a bowed front and is supported on four short legs. The tops are of sarrancolin marble and are cut to conforming shape and have a molded fore edge. The facades of the corner cupboards are occupied by two doors, with the lock on the right door.

Each door carries a large mount that frames the lacquer panel with which it is veneered. The mount consists of flat interlocking C- and S-scrolls bordered by flame motifs and smaller inner C-scrolls above, a climbing plant bearing berried stems emerging from leafy corollas, and a twining branch below. The right-hand doors carry the overlapping central mounts of the lower and upper frame. The mount above consists of a central cabochon topped by five feathers, all set on a stippled ground and framed by foliate C-scrolls. Below hangs a berry-filled leaf cup. The mount at the center of the lower frame consists of a large trilobed cabochon surrounded by flame motifs and flanked by foliate scrolls.

The upper corners of the frame are set, between addorsed C-scrolls, with foliate mounts that extend toward the corners of the doors. Each consists of a leafy corolla bearing a seedpod and leafy twigs. Carrying berries and leaves, another corolla extends from below. The keyhole is surrounded by a large pierced escutcheon backed by a shaped extension of the edge of the right door. It consists of a curved cabochon held between leafy scrolls, topped by a fan or shell motif. Below hangs a pendant of corollas of diminishing size between two pierced C-scrolls that are edged with cartilaginous shellwork. The arrangement terminates in a curled leaf.

Serving as a central foot, the apron is set with a large pierced mount consisting of a central rising leafy branch flanked by large C-scrolls supported by more foliate C- and S-scrolls. The outer surfaces of the short legs are also set with pierced mounts. Each takes the form of a large C-scroll set on its outer edge with a shell-like border, all set against a vertical S-scroll. The inner edge of the foot mount consists of foliate scrolls above a double C-scroll, which together frame the inner profile of the leg.

The vertical gap between the doors is covered by a gilt bronze strip attached to the edge of the right-hand door. The edges of the strip undulate and carry a short flame motif border. The center of the strip is set with a repeating arrangement of two cabochons between small leafy twigs, all set on a rippled, shell-like ground. A simple gilt bronze molding runs horizontally above the doors and down the outer edges of the front. A wider molding runs below the doors.

The panel of lacquer on the left-hand door of .1 depicts in the foreground and the middle ground a rocky shoreline against which waves break. In the background a temple stands on a rocky mountain planted with trees and bushes. Below is a series of low buildings; two buildings with thatched roofs stand on the shore.

The scene continues, with a slight gap, on the door on the right. Waves break on a similarly rocky shore, planted with grasses, bamboo, various coniferous trees, and a shrub bearing red berries. Two pheasants are perched on the top of the highest rock. The background is empty.

The panel of lacquer on the left-hand door of .2 shows waves breaking on a hilly shore, planted with grasses and leafy shrubs. A magnolia tree spreads its branches to either side of a dead willow. Spotted deer, a buck and a doe, stand below the tree. The background is empty.

The right-hand door illustrates waves breaking in an inlet, which is set with three low, roofed buildings backed by trees. In the middle ground a temple stands on a high rock backed by trees of various species. In front of the temple stand two stags and a doe. In the background is a higher mountain, painted with both gnarled and flowering trees.

The remaining surfaces of the facades of each corner cupboard are painted with black European lacquer. The upper friezes are outlined by frames of gold paint. Similar borders outline the entire lower sections of the corner cupboards, consisting of the feet and the aprons.

The inside surfaces of the doors are veneered with cherry and set with frames of amaranth. Each interior is fitted with two fixed shelves (fig. 4-1).

Marks

Each cupboard is stamped “B.V.R.B.” twice on the top of the carcass (fig. 4-2).

Commentary

The corner cupboards are stamped “B.V.R.B.,” for Bernard II van Risenburgh.1 They are of similar form and carry mounts of the same model as a number of other corner cupboards stamped with his initials or attributed to him:2 a pair, stamped and veneered with end cut floral marquetry is at the Residenz, Munich;3 a pair, stamped and veneered with Coromandel lacquer, the gilt bronze mounts struck with the crowned C, is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, in the Wrightsman collection (fig. 4-3);4 a pair, unstamped and veneered with end cut floral marquetry, appeared on the art market in the 1990s.5

Figure 4-3

Figure 4-3The Wrightsman pair, which can be dated to between 1745 and 1749, have bombé profiles and lack the central escutcheon mount. The mount on the central leg is a modern addition. None of the corner cupboards listed above or noted have mounts on their feet. The central mount is of the same model as that found on the aprons of a pair of corner cupboards stamped by Van Risenburgh that were formerly part of a suite that included a pair of commodes in the collection of the Museum (see cat. no. 7) but were unfortunately destroyed in Dresden during World War II.6 It is also found at the center of the plinth of a clock and cabinet at Waddesdon Manor. The cabinet, dated by Geoffrey de Bellaigue to about 1761–65, is stamped “B. Durand,” for Bon Durand, but bears other mounts associated with the work of Van Risenburgh; the cabinet may in fact be by Van Risenburgh but stamped by Durand as a marchand, or restorer.7 Beneath these mounts on the Museum’s cupboards, the profile of the feet and the lower edge of each cupboard are edged with gold paint. This now partly hidden decoration is also found on a pair of slightly later corner cupboards by Van Risenburgh previously in the possession of Bernard Steinitz.8 The large framing mounts are also found on two bouts de bureau by Van Risenburgh, one in the State Hermitage in Saint Petersburg and the other in the Museum (see cat. no. 3).9

Van Risenburgh appears to have made only two pairs of two-door corner cupboards and a single one veneered with lacquer.10 He seems to have had a problem with the meeting of the doors, and there is a noticeable gap on the Coromandel pair of the Wrightsman collection discussed above. A larger gap between the doors of the Museum’s pieces has been masked by the application of a vertical strip of gilt bronze. This mount does not appear elsewhere in Van Risenburgh’s oeuvre and is believed to be an eighteenth-century replacement (see “Technical Description” below).

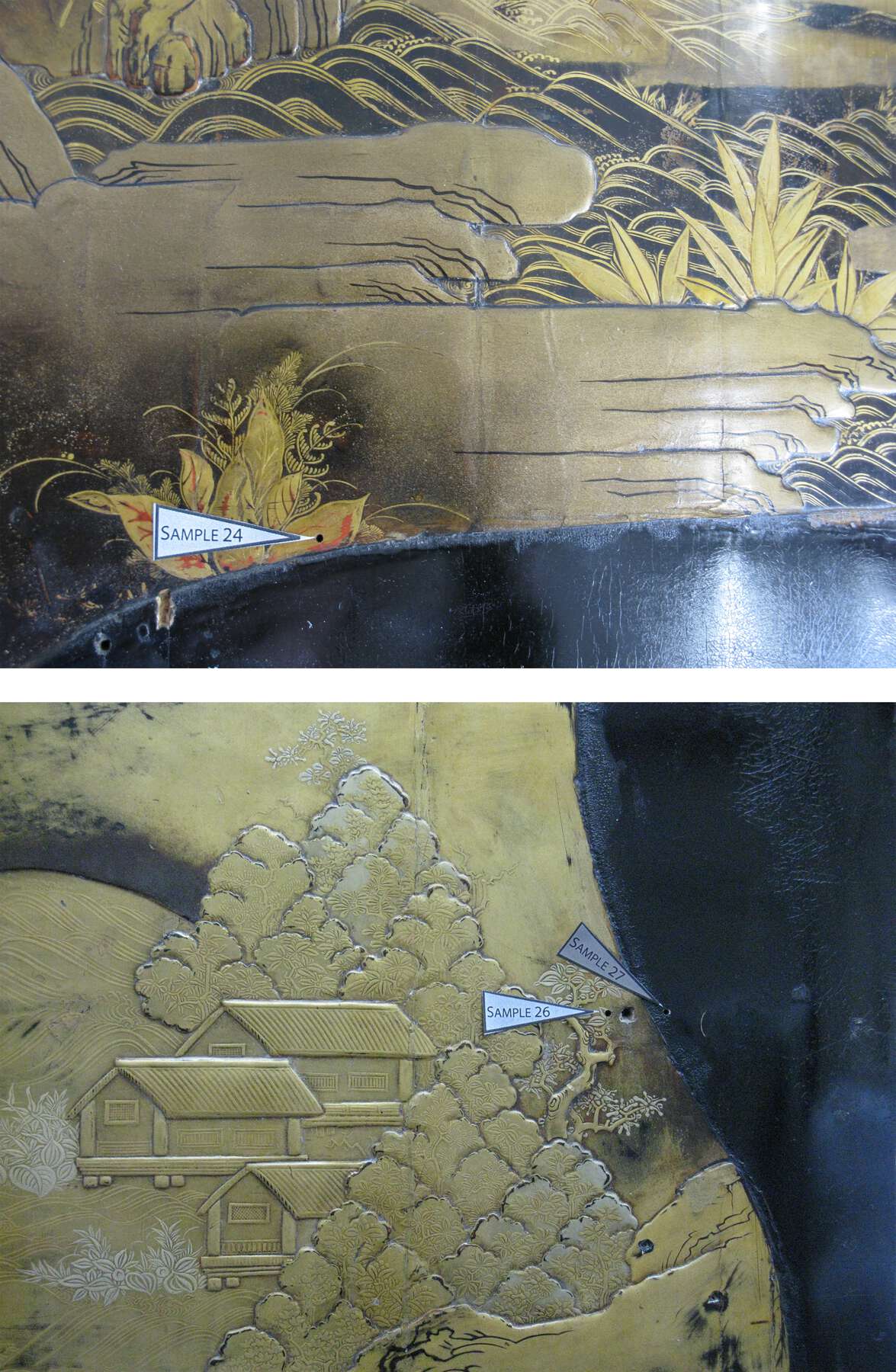

The four fine panels of Japanese export lacquer have been cut from the doors of two fairly large cabinets that were not a matched pair (see “Technical Description” below). Oliver Impey dated the lacquer to the 1650s. Documents from the Dutch East India Company record the acquisition of paired cabinets up to 1640, but none were imported between that date and 1660, when they appear again. It is of course possible that they were imported later as old lacquer by the French East Indies Company.11 Filled pinholes beneath the gilt bronze framing mount can be seen clearly near the outer edge where the straps of the original hinges were positioned. Ghosts of the metal hinge tab impressed on the lacquer can also be seen (fig. 4-4). The original cabinets possessed six hinges on each door, whereas five was the normal number.12 A lacquer cabinet on a French giltwood stand in the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal is of the type that would have been provided to Van Risenburgh by a marchand-mercier;13 a similar cabinet passed through the French market in 1993.14 One of this form appears in the 1740 trade card of Gersaint, drawn by François Boucher.15 However, it seems certain that by this date Van Risenburgh would have received the four doors from the marchand-mercier Hébert, for whom he worked.16

Figure 4-4

Figure 4-4Provenance

–1972: Kraemer et Cie (Paris, France), sold through French and Company to the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1972.17

Bibliography

, 139; , 30, no. 33; , 263, fig. 132; , 19, no. 33; , 94, 96, figs. 3–4, 7–8.

Exhibition History

The J. Paul Getty Collection of French Decorative Arts, Detroit Institute of Arts (Detroit), October 3, 1972–August 31, 1973.

- G.W.

Technical Description

The carcasses of the two cabinets are made of white oak and are very nearly identical in construction. The two front corner posts run from the floor to the top of the case and are shaped from single blocks measuring approximately 5.5 cm wide x 7 cm deep in section. Above and below the doors, the posts are connected with curved, compound rails, each of which is composed of three pieces of wood. The upper portion of these compound rails is a single bow-shaped horizontal board approximately 1.5 cm thick and 17 cm deep at its widest point (fig. 4-5). In the upper rail, the transverse board is joined to the posts with single, angled dovetails; in the lower rail, it is attached with sliding dovetails that run parallel to the case sides (fig. 4-6). The lower portion of each upper and lower compound rail is formed of two blocks, joined end to end at the center, that follow the curved contour of the case front. These two blocks are approximately 4 cm thick and are glued to the underside of the transverse board. In the upper rail, the blocks are joined to each other at the center with a slip joint and joined to the posts with sliding dovetails that run parallel to the case sides; in the lower rail, the blocks appear to be glued in place only, without any joinery at either end.

The rear leg is made from two thin vertical boards joined in an L-shape with a rabbet-and-groove joint running along their entire length. Below the level of the bottom shelf, the back leg is reinforced with a large corner block of oak. The rear leg assembly is joined to the front posts with rails at top and bottom that are attached with unpinned mortise-and-tenon joints (fig. 4-7). At the front, where the rails join the heavy posts, the tenons are single-shouldered; at the rear, the tenons are double-shouldered where they join the much thinner back leg. The rails and posts frame a single panel on each case side. The panels are made of from three to four boards, butt joined, with the grain oriented vertically; they have been simply chamfered along the outer edges and are flat on their inner surfaces.

The case tops are made in frame-and-panel construction; two side rails are attached to the front posts with single dovetails and are joined to each other at the rear with mitered half-lap joints. The side rails of the top are attached to the upper rails of the case sides with long tongue-and-groove joints. The panels of the tops are made of three boards each, butt joined, with the grain oriented parallel to the case front; they have been chamfered along the bottom edges and are flat on their upper surfaces. The triangular case bottom panels are formed of four butt-joined boards; they are held in place with tongue-and-groove joints along all three sides. The front center feet of the cabinets, as well as the corner brackets of the side feet, have been assembled simply by gluing blocks of wood to the bottom of the case to create the desired profile; this has been done without joinery.

The shelves are each made of from four to five butt-joined boards. They are loose-fitting and rest on transverse battens that are mortise and tenoned to the front posts and nailed to the rear leg assembly.

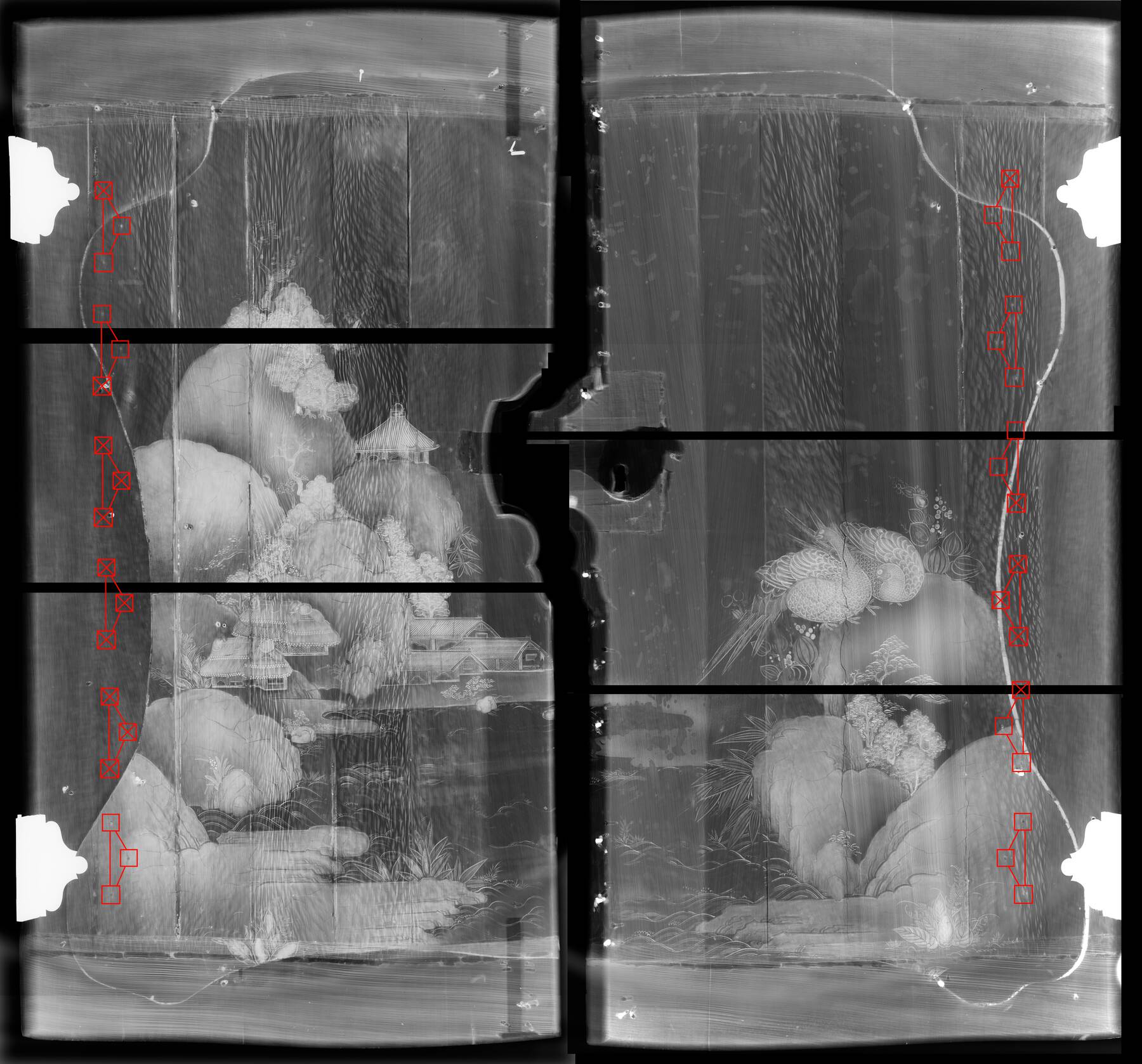

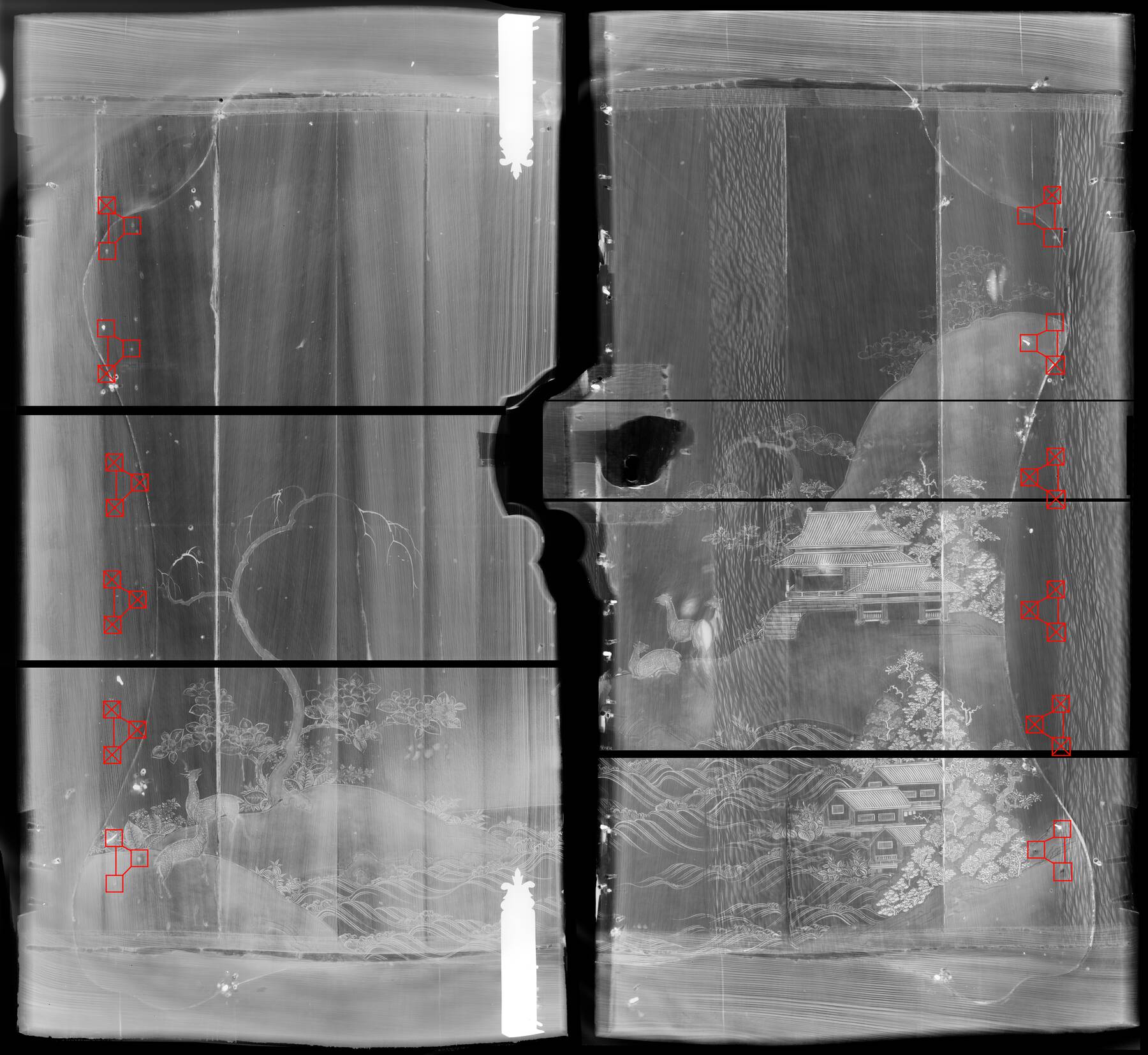

The construction of the doors was determined with the aid of X-radiography. All the doors are constructed in a similar fashion with between five and seven vertically oriented narrow boards butt joined to each other, forming the core of the door; battens are attached at the top and bottom with tongue-and-groove joints, so-called breadboard ends. The protruding section of the right door on each cabinet, which houses the lock mechanism and is covered by the central gilded escutcheon, is a separate piece of wood with its grain oriented horizontally; this has been mortise and tenoned into the edge of the assembled door. This was presumably done for added strength.

The exterior of the cabinets has been veneered with sycamore maple wherever Japanese lacquer is not present; this veneer covers the joints of the cases, reducing the chance that the European lacquer would crack along glue lines. It also raises the surface of the cabinets to be flush with the applied Japanese lacquer panels and provides a smooth and less porous base for the subsequent lacquering. The interior of the doors has been veneered with a combination of cherry and amaranth veneers in a pattern nearly identical to that found on the interior of the doors of the Museum Van Risenburgh commode (see cat. no. 5).

The lacquer panels on the doors of the cabinets are almost certainly taken from the exterior of the front doors of two Japanese cabinets; the lacquer work can be dated stylistically to the period between about 1650 and 1660.18 An intact Japanese cabinet in the collections of Rosenborg Castle in Copenhagen likely bears a resemblance to the original source of these panels (fig. 4-8).

Figure 4-8

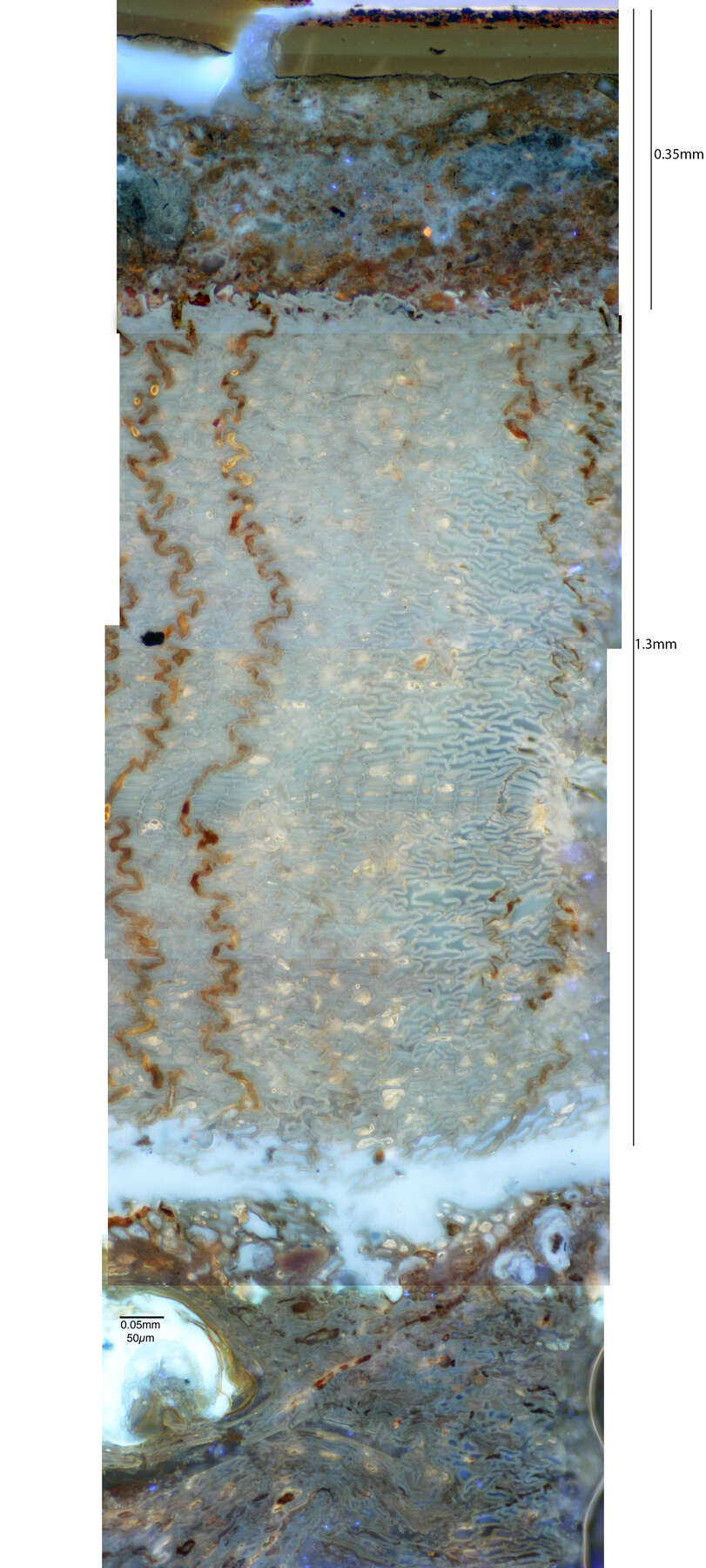

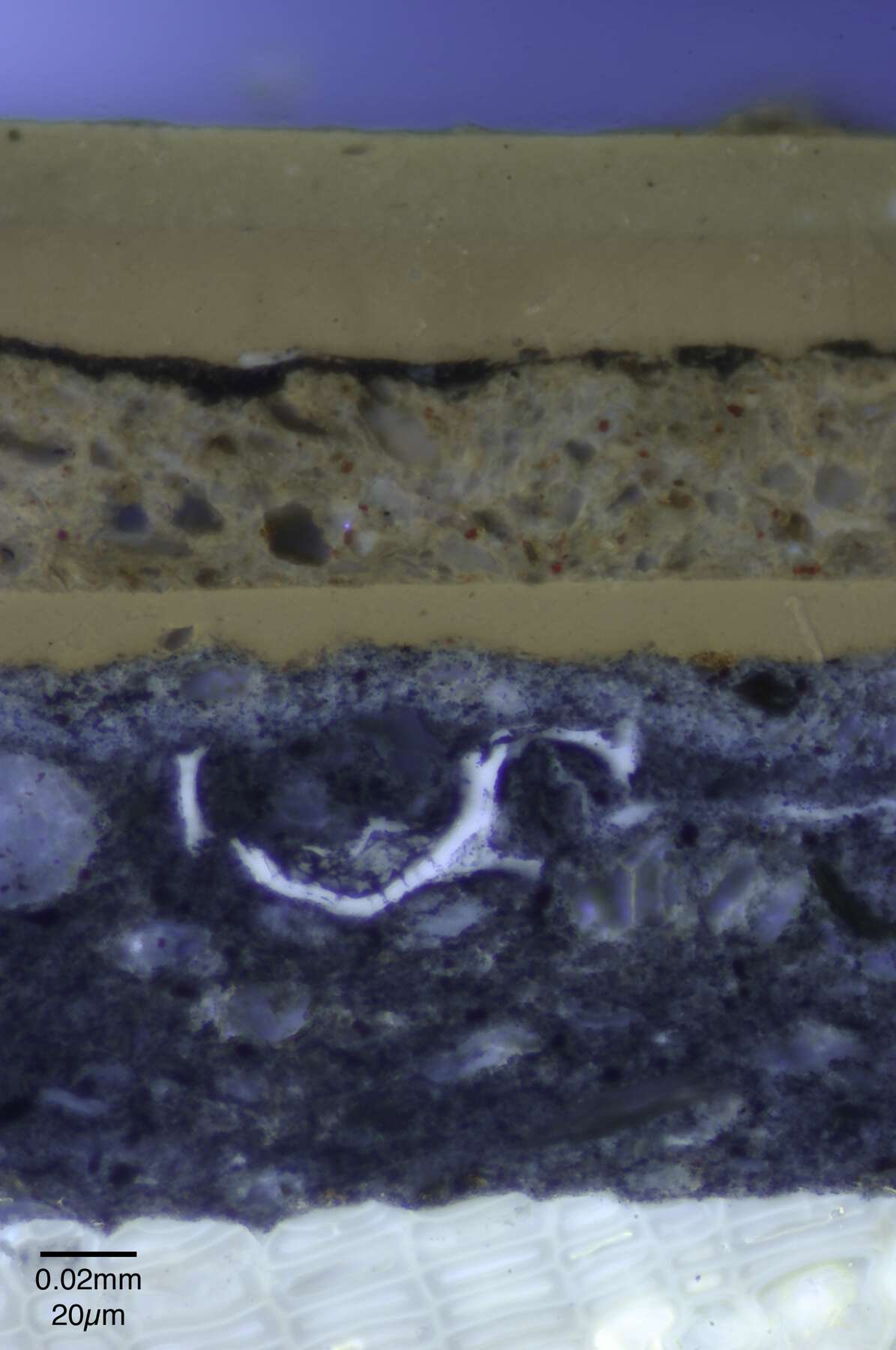

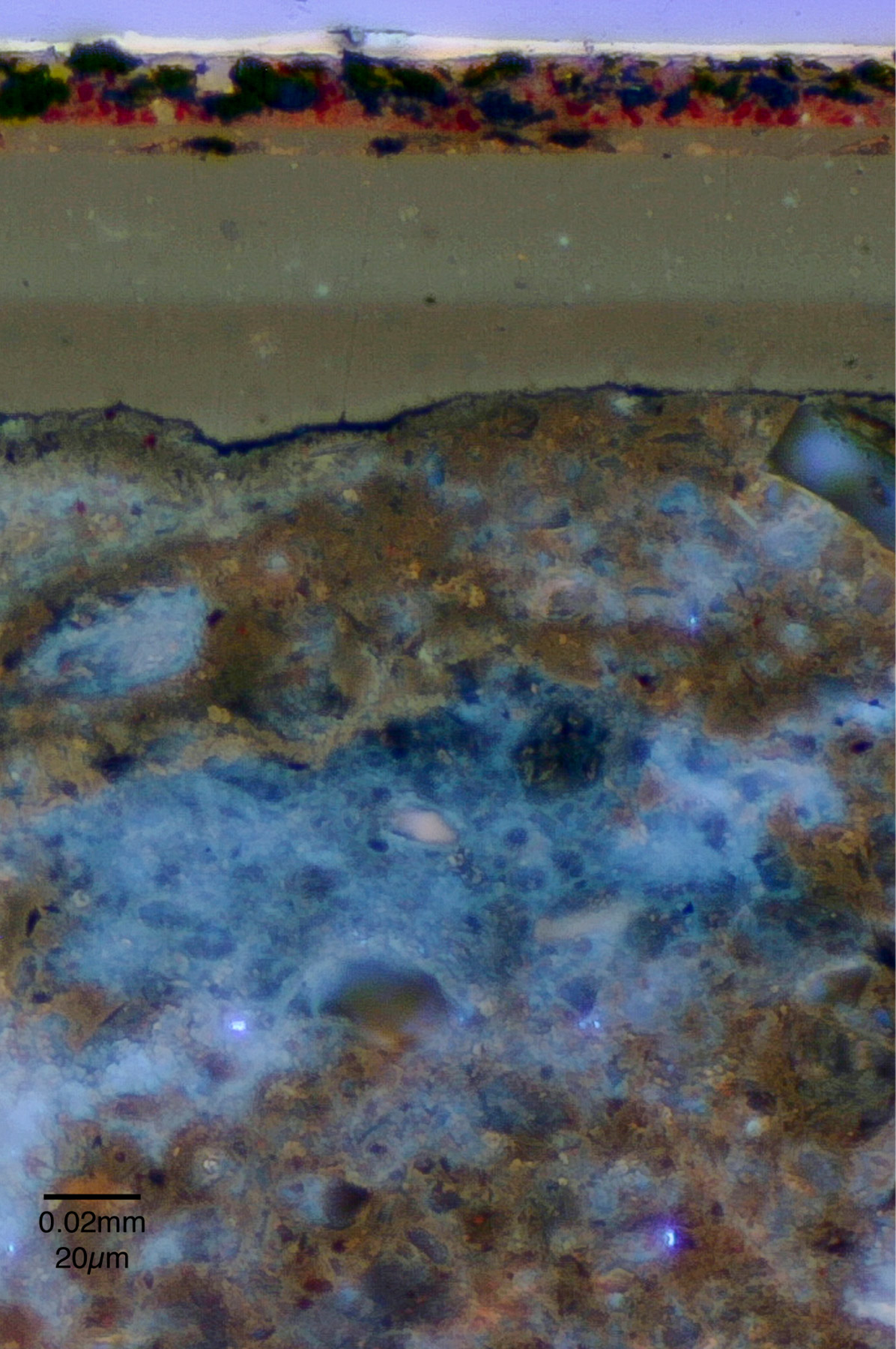

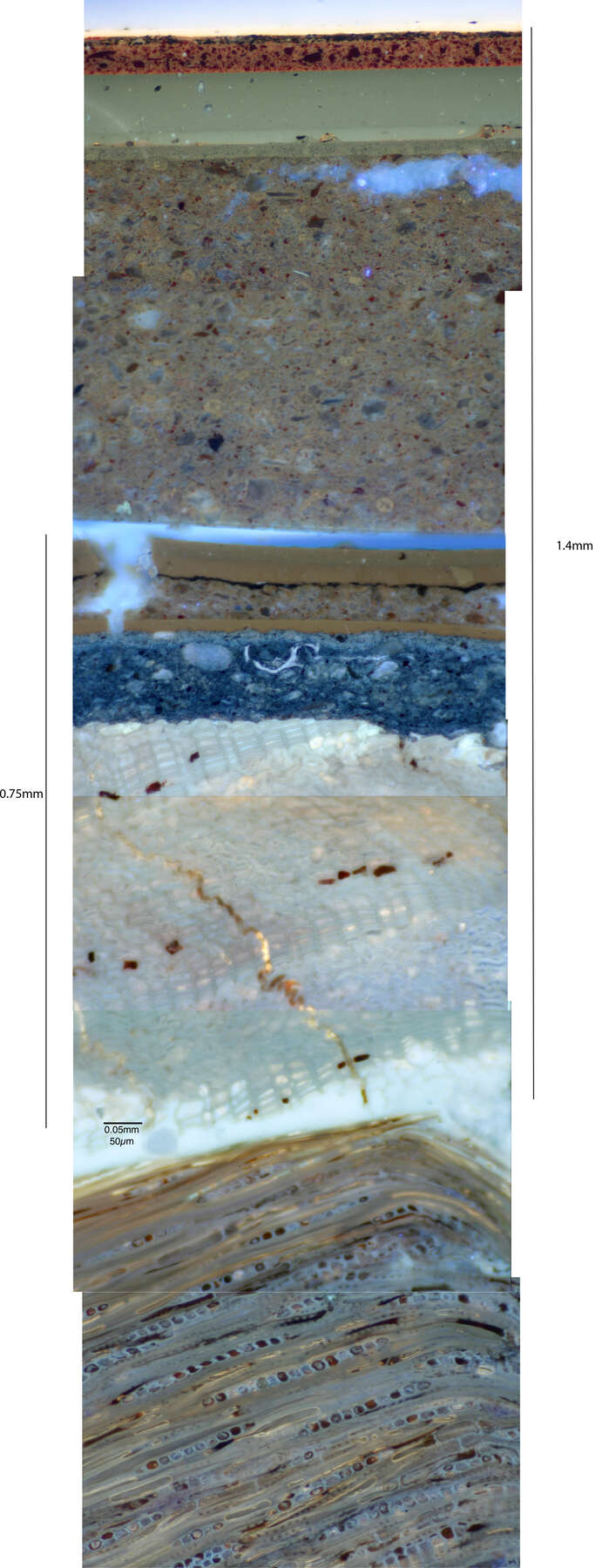

Figure 4-8The lacquer decoration is executed in a wide variety of decorative techniques, including hiramakie (flat designs of sprinkled metal powder), takamakie (similar designs in relief), nashiji (evenly sprinkled metal flakes used as a background texture), keuchi (or tsukegaki; fine, low-relief lines of gold defining the detailed features of floral and architectural elements), and kakiwari (black lines on a gold ground formed by allowing the substrate to show through).19 Cross-section sampling reveals that both the Japanese panels were thinned to between 0.75 and 1.3 mm in thickness (excluding the relief decoration) and that the original wooden substrate for both cabinets is Japanese arborvitae (fig. 4-9).

Figure 4-9

Figure 4-9X-radiographs reveal patterns of nail holes along the outer edges of the panels where the original Japanese cabinet hinges were once fastened (figs. 4-10, 4-11). Careful study of the nail hole patterns shows that both Japanese cabinets had six hinges per door but that the patterns are of distinctly different shape from one to the other. This suggests that the two original Japanese cabinets were not a matched pair but rather were brought together for reuse in this pair of corner cabinets, based on their similar style and size. Several other observations confirm this postulation. For example, the lacquerwork on cabinet .2 uses a very pale greenish-gold powder, particularly in certain areas of keuchi detail; this color of powder, made with a high percentage of silver,20 is conspicuously absent from cabinet .1. In addition, cross-section analysis shows that the lacquer of cabinet .1 uses a black clay ground material that is not present in cabinet .2 (figs. 4-12, 4-13, 4-14). The layer structure observed on cabinet .2 resembles a relatively typical layer structure for Japanese export lacquer.21 This layering includes a thick ground, a thin black layer, two dark translucent lacquer layers, and decorative layers. Cabinet .1 deviates from this commonly observed structure as it has two ground layers, one black and one beige, that are separated by an intermediate layer of lacquer.

Figure 4-10

Figure 4-10 Figure 4-11

Figure 4-11 Figure 4-12

Figure 4-12 Figure 4-13

Figure 4-13 Figure 4-14

Figure 4-14Organic analysis by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and pyrolysis gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (py/GC-MS) emphasizes the differences in the Japanese cabinets, further indicating that they were not a matched pair. The black clay ground material in cabinet .1 is bound predominantly with glue with minor contributions of drying oil and lacquer, whereas the beige ground material used in cabinet .2 contains no glue and is bound primarily with drying oil and lacquer with minor amounts of starch. Unexpectedly, the ground layers from both samples appear to contain small amounts of marker compounds associated with cedar oil. These compounds have been reported in substantial amounts in many examples of southern Chinese export lacquer where they are thought to be linked to the intentional addition of distilled cedar oil derived primarily from Chinese weeping cypress (Cupressus funebris).22 No intentional use of cedar oil in seventeenth-century Japan has been documented to date; it may be more likely, in this case, that the source of these marker compounds may instead be in the underlying wood substrate.23 Japanese arborvitae wood is, like Chinese weeping cypress, a member of the Cupressaceae family and is known to contain a similar range of volatile compounds. Over time, small amounts of these compounds may have migrated into the porous ground layer from the wood substrate.

The py/GC-MS analysis confirmed that the lacquer in both panels is not pure urushi but rather a combination of thitsi lacquer and urushi with a significant amount of drying oil mixed into all layers. Thitsi, imported from Southeast Asia by Dutch and Chinese traders in the seventeenth century, was significantly cheaper than domestically produced urushi; however, it was more viscous, softer when dry, darker, and slower to cure than the more expensive urushi.24 The practice of adding oil to the lacquer is typical of Asian export lacquers of the period as it allowed layers to be built up more quickly and adds gloss without laborious polishing but was eschewed in high-quality Japanese domestic wares because it reduced the durability of the final product. It is possible that the transparent lacquer layers on cabinet .2 and the takamakie ground and lacquer layer on .1 also include small amounts of “wood oil,”25 perhaps added to the thitsi lacquer as a diluent to improve the working properties during application or as an adulterant by unscrupulous traders.26

From cross-section analysis along with further organic analysis and electron microscopy, it is also possible to garner a better understanding of the takamakie decoration on cabinet .1. This decorative scheme was built up in a complex series of layers applied on the lacquer surface and likely incorporates multiple campaigns of decorations (fig. 4-15). The takamakie relief was created with urushi and thitsi lacquer with drying oil mixed with clay, a small amount of glue, and possibly wood oil. The layer, measuring more than 0.5 mm thick in this sample, was applied to the polished lacquer surface to create the area of relief within the landscape design. The thick ground layer was coated with a layer of lacquer pigmented with carbon black, followed by a second transparent lacquer layer onto which the spinkled decoration was created in gold and vermilion.27 A second decorative campaign was applied above the takamakie decoration and depicts the fine foliage in lacquer mixed with vermilion and covered with gold leaf.

Figure 4-15

Figure 4-15The Japanese lacquer panels were overcleaned in the course of restorations prior to their acquisition by the Museum. This caused abrasion and loss to some areas of the decoration; this damage has been largely retouched, as have several long vertical cracks, particularly in the areas of high relief. The surface has also been heavily coated with restoration varnishes, at least one of which consists of shellac (as identified by py/GC-MS and confirmed by the characteristic orange fluorescence of the surface in ultraviolet illumination) (fig. 4-16).

Figure 4-16

Figure 4-16The French imitation black lacquer surrounding the Asian panels has been repainted at least two times; however, the original material does seem to be present below the repainting in many areas. Organic analysis along with scanning electron microscopy with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) suggests that the original French lacquer was executed in three basic steps. First, a white chalk filler or putty containing a mixture of drying oil, resins, and glue was likely locally applied to select areas of the wood to smooth the transition between the Asian lacquer and the European veneer. The resin fraction appears to be a mixture of pine resin, shellac, gum benzoin, and a polycommunic diterpenoid resin (likely sandarac, based on its use in the layers above). While this layer appears to be a continuous ground layer when viewed in cross section, its unusual organic composition, proximity to joins, and variable thickness between samples set it apart from traditional eighteenth-century preparation techniques for European lacquer. Typically, a close-grained veneer served to provide a smooth substrate to lacquer directly, not requiring the use of a calcium carbonate ground (see Dubois corner cupboards; cat. no. 12).28 Period sources indicate that a chalk putty consisting of calcium carbonate mixed with varnish could be used to cover cracks and joints in the wood.29 As the sample comes from an area near where the European lacquer meets the Asian panel, it was likely necessary for the craftsman to use a filler to seamlessly merge the two in this location. Following the preparatory layer, a black paint layer was applied; this was composed of bone (or ivory) black pigment bound in a spirit-resin varnish that contains a mixture of shellac, pine resin, sandarac, larch turpentine, and a small amount of drying oil. The use of sandarac, shellac, and larch turpentine is indicative of a high-quality eighteenth-century varnish. Last, the pigmented layer was followed by one or more coats of transparent varnish with composition similar to that of the pigmented layer underneath.

The gilt bronze mounts on the cabinets appear to be largely original. The only exception seems to be the two vertical mounts on each cabinet that cover the joint between the doors, above and below the central escutcheon. These mounts do not match the others stylistically; they are slightly more greenish in tone, and they are inexpertly fitted with adjacent mounts. The alloy composition of the metal (as determined by X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy [XRF]) is distinctly different from that of the other mounts, though it can still be considered typical of eighteenth-century casting brass. X-radiography reveals an additional set of filled screw holes below the vertical mounts, suggesting that there is likely to have been a different set of mounts covering the joint between the doors in the past. All of the other mounts on the commodes are finely and consistently chased and neatly fitted. The composition of the brass is very consistent between mounts and is typical of period alloys with respect to most elements; only the zinc levels are unusually high, at an average of about 25%, compared to the more usual 13 to 23%. The zinc content of all four measured samples of soldering metal is also unusual, averaging around 36%. This almost certainly implies the use of expensive spelter brass, which was rare though not unknown in mid-eighteenth-century France.30

The stone tops are 3.5 cm thick and are made of a marble (metamorphic limestone) known as sarrancolin; this has a multicolored brecciated pattern, with large (up to 30 cm) chunks of striated cream, and granular gray fragments in a red-to-orange smooth-textured matrix. White and tan veins cross through the breccia pattern. Sarrancolin marble is very similar to Marmor Chium (also known as Portasanta) from Greece. Marmor Chium, however, was mainly quarried in ancient Roman times, and only small pieces made it beyond Italy during the Renaissance. The two can be distinguished based on their fossil inclusions; sarrancolin often contains rudist bivalves within the gray and in the reddish matrix dating to the Cretaceous period, while Marmor Chium contains fossils of Triassic echinoderms. Sarrancolin marble comes from the Pyrenees Mountains, and was actively quarried in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries. There are several types of sarrancolin marble; this is most similar to stone from the eastern slopes of the Aure Valley, near Beyrede-Jumet, in the Hautes-Pyrénées, France.

- A.H.,

- J.C.,

- M.S.,

- and R.S.

Notes

For more information on Bernard II van Risenburgh, see primarily , 183–99; , 56–63. See also Daniel Alcouffe, in , 323–24. ↩︎

Other examples exist of the same size and form but lacking some or all of the mounts:

a. A pair sold at Sotheby’s, The Distinguished Collection of a Lady, December 9–11, 1997 (Zurich: Sotheby’s, 1997), lot 315, stamped “B.V.R.B.,” veneered with plain veneers and banding. The elaborate central escutcheon is present, but the framing mount is an adaptation of that found on the Museum’s commode, cat. no. 5 (84 x 75 x 54 cm); ex. coll. Ernest Cronier, sold, Galerie Georges Petit, Tableaux anciens et modernes, December 4–5, 1905 (Paris: Galerie Georges Petit, 1905), lot 145; ex. coll. Bloch-Levalois, sold, Paris, May 25–26, 1924, lot 128; sold again, Sotheby’s, Important mobilier, sculpture et objets d’art, April 16, 2013 (Paris: Sotheby’s, 2013), lot 79.

b. A pair in the salon of the château de Champs-sur-Marne. Of the same profile and central escutcheon in end cut floral marquetry but lacking the framing mounts. Stamps unknown. Documents consulted at the archives of the Centre de Recherche Historique sur les Maîtres Ébénistes.

c. A single corner cupboard, sold Parke-Bernet Galleries, English and French XVIII Century Furniture, Parke-Bernet Galleries, May 28–29, 1941 (New York: Parke-Bernet Galleries, 1941), lot 432. Apparently unstamped. Same form and profile, veneered with trellis marquetry surrounded by banding and a shaped frame of wood veneer that would have served as a background to the now-missing framing mount. No mounts (3 ft. x 2 ft. 7 in.). ↩︎

Acc. no. Res. Mü. M 23, 24 (89.5 x 76 x 53.5 cm). , 111–13, no. 20. ↩︎

Acc. no. 1983.185.1a, b, .2a, b (2 ft. 11 7/8 in. x 2 ft. 9 7/8 in. x 2 ft. 2 1/8 in.; 91 x 86 x 66.4 cm). , vol. 1, 170–73, nos. 100A and 100B. Now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles Wrightsman. ↩︎

Sold, Christie’s, Important Furniture, Porcelain, Clocks and Carpets, April 26, 1994 (New York: Christie’s, 1994), lot 297; also sold, Christie’s, Important French Furniture, Objects of Art and Sculpture, October 26, 1994 (New York: Christie’s, 1994), lot 85; and with the dealer Röbbig-München in 1996, published in their catalogue Frühe deutsche Porzellane, Einrichtungen und Objekte des 18. Jahrhunderts (Munich: Röbbig-München, 1996), 38–39. 2 ft. 11 in. x 2 ft. 7 in. x 1 ft. 10 3/4 in. (89 x 78.7 x 58 cm). ↩︎

, 325, fig. 277. ↩︎

, vol. 1, 186–88, no. 39. ↩︎

, 12, fig. 4. ↩︎

, 189, no. 93 (inv. no. MB 434). , 52, no. 14. ↩︎

See a single double-door corner cupboard set with a shaped panel of Japanese lacquer and bearing mounts found on other pieces stamped by Van Risenburgh and securely attributed to him in , 46, fig. 6. Present location unknown. ↩︎

Conversation with Oliver Impey, October 1992, notes in the files of the Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

See , 33, fig. 15, for a pair of cabinets without stands, in their original form. Sold, Christie’s, Export Art of China and Japan, April 7, 1997 (London: Christie’s, 1997), lot 164 (68.1 x 42.7 x 52.7 cm). See also a cabinet-on-stand at Rosenborg Castle, Copenhagen, for the type of model that may well have been used (fig. 4-8). The doors with six hinges each are painted with watery and rocky landscapes. See , 134, fig. 269, where the cabinet is dated about 1640–90. ↩︎

, 80, pl. 46. ↩︎

Hôtel des ventes Neuilly, Tableaux anciens et XIXe siècle, bijoux, argenterie, objets d’art et de très bel ameublement des XVIIIe et XIXe siècles, May 10, 1993 (Paris: Hôtel des ventes Neuilly, 1993), lot 85. H including stand: 131 x 72 x 47 cm. ↩︎

, 81, pl. 47. ↩︎

For a detailed account of the import of lacquer into France, the activities of the French East Indies Company, the marchand-merciers who bought the lacquer and the cabinetmakers who worked with it, see ; . See also , 177–98. ↩︎

Memorandum from Frank Whitworth to Norris Bramlett, March 30, 1972, in the files of the Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

For images of related Japanese cabinets and a discussion of dating styles, see . ↩︎

For a comprehensive discussion of Japanese lacquer techniques, see . ↩︎

The high silver content of this gold powder was confirmed by energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). ↩︎

See discussion in . ↩︎

, 34–35. ↩︎

, 104. ↩︎

, 104. ↩︎

Marker compounds for Dipterocarpus resin have been frequently detected in lacquer samples containing thitsi lacquer. , 99–100, provides a range of possible scenarios to account for the inclusion of wood oil in thitsi lacquer coatings. ↩︎

As reported in , 101, several of the layers contain marker compounds for gum benzoin. However, this set of markers was not considered conclusive enough to confirm the presence of this material at this time. ↩︎

Shellac markers were detected in this sample from .1 but are also observed in a trace amount in the upper layers of cabinet .2. It is unclear at this time if these materials were intentionally added to the Asian layer or rather relate to contamination from upper restoration varnishes. See RAdICAL Reports 29-13 and 28-8 in the Decorative Arts and Sculpture Conservation Department, J. Paul Getty Museum, for additional information on marker identification. ↩︎

, 113; , 34. ↩︎

, 136–37. ↩︎

Prior to the nineteenth century, cementation was the standard process by which zinc was added to copper to produce brass. Powdered zinc oxide or carbonate was placed in a crucible with small pieces of copper metal and charcoal and then heated in a reducing atmosphere to a temperature just below the melting point of copper. Under these conditions, the zinc was reduced and vaporized, allowing it to diffuse slowly into the surrounding copper, thus forming brass. Typically, brass produced by this method will have a zinc content of less than 33%, although higher levels have been shown to be possible. (For an excellent discussion of this topic, see .) The industrial production of metallic zinc, which facilitates the production of higher zinc content in brass, was developed on a limited scale in England beginning in the 1740s. However, continental production of zinc metal on a significant scale did not take place until the last years of the eighteenth century, before which time access to metallic zinc was limited to minor production in Germany and costly importation from India and China; see ; “Zinc,” in Ullman’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 5th rev. ed., vol. A28, ed. Barbara Elvers, Stephen Hawkins, James F. Rounsaville, and Gail Schulz (Weinheim: VCH Verlagsgesellschaft; Deerfield Beach, FL: VCH Publishers, 1996). ↩︎

Bibliography

- Baroli 1957

- Baroli, Jean-Pierre. “Le mystérieux B.V.R.B. enfin identifié.” Connaissance des Arts 61 (March 1957): 56–63.

- Birioukova 1974

- Birioukova, Nina. Les arts appliqués de l’Europe occidentale, XIIe–XVIIIe siècles. Leningrad: Aurora, 1974.

- Bremer-David et al. 1993

- Bremer-David, Charissa, et al. Decorative Arts: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue of the Collections of the J. Paul Getty Museum. Malibu, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1993.

- Day 1990

- Day, Joan. “Brass and Zinc in Europe from the Middle Ages to the 19th Century.” In 2000 Years of Zinc and Brass, edited by P. T. Craddock, 123–50. Occasional Papers. London: British Museum Publications, 1990.

- De Bellaigue 1974

- De Bellaigue, Geoffrey. The James A. de Rothschild Collection at Waddesdon Manor: Furniture, Clocks and Gilt Bronzes. 2 vols. Fribourg: Office du Livre, 1974.

- Feulner 1927

- Feulner, Adolf. Kunstgeschichte des Möbels. Berlin: Propyläen-Verlag, 1927.

- Heckmann 2002

- Heckmann, Günther. Urushi no waza. Ellwangen: Nihon Art Publishers, 2002.

- Heginbotham and Schilling 2011

- Heginbotham, Arlen, and Michael Schilling. “New Evidence for the Use of Southeast Asian Raw Materials in Seventeenth-Century Japanese Export Lacquer.” In East Asian Lacquer: Material Culture, Science and Conservation, edited by Shayne Rivers, Rupert Faulkner, and Boris Pretzel, 92–106. London: Archetype in association with the Victoria and Albert Museum, 2011.

- Heginbotham et al. 2016

- Heginbotham, Arlen, Julie Chang, Herant Khanjian, and Michael R. Schilling. “Some Observations on the Composition of Chinese Lacquer.” Studies in Conservation 61, suppl. 3 (2016): S28–S37. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00393630.2016.1230979.

- Impey and Jörg 2005

- Impey, Oliver, and Christiaan Jörg. Japanese Export Lacquer, 1580–1850. Amsterdam: Hotei, 2005.

- Jullian 1962

- Jullian, Philippe. “Comment identifier le vernis Martin.” Connaissance des Arts 119 (January 1962): 42–49.

- Kjellberg 1989

- Kjellberg, Pierre. Le mobilier français du XVIIIe siècle: Dictionnaire des ébénistes et des menuisiers. Paris: Éditions de l’Amateur, 1989.

- Langer and Ottomeyer 1995

- Langer, Brigitte, and Hans Ottomeyer. Die französischen Möbel des 18. Jahrhunderts. Vol. 1, Die Möbel der Residenz München. Munich: Prestel, 1995.

- Louis XV . . . 1974

- Louis XV, un moment de perfection de l’art français. Exh. cat. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1974.

- Pradère 1989a

- Pradère, Alexandre. French Furniture Makers: The Art of the Ébéniste from Louis XIV to the Revolution. Malibu, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1989.

- Rappe 2016

- Rappe, Tamara. Un siècle d’élégance française: A Century of French Elegance (at Paris, Biennale des Antiquaires). Exh. cat. Dijon: Éditions Faton, 2016.

- Sargentson 1996

- Sargentson, Carolyn. Merchants and Luxury Markets: The Marchands Merciers of Eighteenth-Century Paris. London: Victoria and Albert Museum in association with the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1996.

- Vittet 2009

- Vittet, Jean. “Le marchand Thomas-Joachim Hébert (1687–1773) et l’ébénisterie de son temps.” In Le commerce du luxe à Paris aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles: Échanges nationaux et internationaux, ed. Stéphane Castelluccio, 177–98. Bern: Peter Lang, 2009.

- Walch 1997

- Walch, Katharina. “Baroque and Rococo Transparent Gloss Lacquers: I. The Replication of White Lacquers on the Basis of Historic Sources and Scientific Examination” and “Baroque and Rococo Red Lacquers: The Red Lacquer-work in the Miniaturenkabinett of the Munich Residenz. Replicating the Technique on the Basis of Historic Sources and Scientific Inverstigation.” In Lacke des Barock und Rokoko = Baroque and Rococo Lacquers, edited by Katharine Walch and Johann Koller, 21–52 and 129–44. Munich: Bayerisches Landesamt für Denkmalpflege, 1997.

- Watson 1966

- Watson, Francis John Bagott. The Wrightsman Collection. 5 vols. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1966.

- Webb 2000

- Webb, Marianne. Lacquer Technology and Conservation: A Comprehensive Guide to the Technology and Conservation of Both Asian and European Lacquer. Butterworth-Heinemann Series in Conservation and Museology. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2000.

- Welter 2003

- Welter, Jean Marie. “The Zinc Content of Brass: A Chronological Indicator,” Techne, no. 18 (2003): 27–36.

- Wilson and Hess 2001

- Wilson, Gillian, and Catherine Hess. Summary Catalogue of European Decorative Arts in the J. Paul Getty Museum. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2001.

- Wolvesperges 2000

- Wolvesperges, Thibaut. Le meuble français en laque au XVIIIe siècle. Paris: Éditions de l’Amateur, 2000.