19. Writing and toilette table

- French (Paris), ca. 1760–70

- By Jean-Francois Oeben (French, born Germany, 1721–1763, ébéniste mécanicien du Roi from 1760, master 1761) and workshop

- White oak* veneered with kingwood, tulipwood, amaranth, boxwood, holly*, barberry*, stained hornbeam, bloodwood, sycamore maple*, stained maple*, ebony; leather; silk* fabric lining; gilt bronze mounts; brass and iron fittings and lock; iron screws

- H: 2 ft. 4 in., W: 2 ft. 7 1/2 in., D: 1 ft. 6 1/8 in. (71.1 × 80 × 46 cm)

- 71.DA.103

Description

The table of rectangular shape is supported on four cabriole legs that are five sided in section. The front is double bowed, the sides serpentine and bowed, and the back single bowed. The top is of conforming shape and is surrounded by a flat molding with raised edges, forming a shallow rim on the top. Each corner is set with a gilt bronze mount consisting of a bearded and mustachioed Chinese head supported on a stippled shaft from which depend three husks. Above the head spring acanthus leaves that cross. The upper part of the mount is formed by a scallop shell, and a separate simple molding extends down the outer edge of each leg to the foot. The serpentine lower edge of the frieze is set with leafy moldings that extend down the inner edges of each leg. Each foot is clad with a mount that consists of leafy scrolls set to either side of a cabochon, above a lipped extension.

The tabletop (fig. 19-1) is veneered with a complex panel of marquetry. At the center is a low-walled wicker basket filled with flowers, among which roses, tulips, narcissus, and honeysuckle can be identified. The basket sits on a shaped plinth that is faced with a large scallop shell and panels of burl wood. To each side of the plinth a broad frame extends around the outer surface of the tabletop. Above, it supports a shallow trellis, from the center of which depends a double garland of flowers that extends to each corner. Here they are threaded through the frame to hang down at either side. The flowers forming the swag have not been cut to give much detail, but among them roses, poppies, daisies, honeysuckle, and convolvulus may be recognized.

At the corners of the tabletop are animals representing the four elements. A dove representing Air is perched on a small cloud on the upper left. Below on the lower left is a swan, representing Water, which sits on a scrolled extension of the broad frame and is backed by a stand of bullrushes. On the upper right, a salamander, representing Fire, is perched on a leafy scroll and is surrounded by flames. Below, on the lower right, sits a lion, representing Earth. Its front legs are set on an extension of the plinth, its back legs supported by a scroll. Behind rises a leafy tree carrying a single fruit.

Various elements of the marquetry—the flowers, the leaves, and the scallop shell, for example—bear some evidence of scorching, and much of the green stain has survived in the leaves and the maple burl wood veneers. The friezes of the table are veneered with shaped marquetry panels of trellis, with circles at the crossings. The squares formed are filled with four petaled flowers in a barberry. Each panel is outlined by holly and black-dyed maple stringing, and the remaining surfaces of the frieze are veneered with tulipwood. The outer surfaces of each leg are set with narrow panels of maple burl wood, outlined with holly and black-dyed maple stringing. Situated above each panel, at the junction of the leg with the frieze, is a similarly outlined oval panel of maple burl wood. The remaining surfaces of the legs are veneered with tulipwood.

The body of the table is occupied by a large lockable drawer, the front of which, with the exception of a narrow upper border of tulipwood, is veneered with a panel of trellis marquetry. The drawer is covered by a sliding lid. The surface of the lid carries a large kidney-shaped panel of leather, which has been stained with marbleized designs. Its border is tooled and gilded with stylized pomegranates, clover, leafy scrolls, stars, and dots. Below is a small panel of maple burl wood veneer and to either side a panel of trellis marquetry. The remaining area of the lid is veneered with tulipwood, and all these fields are outlined with holly and black-dyed maple stringing.

Pressure on a gilt bronze stud set at the front of the lid activates a steel catch, enabling the lid to be manually slid back when the drawer has been opened. The catch connects with a second catch located in the forward interior surface of the drawer, which itself may be activated by pressure on a lever set below the drawer. The latter action is necessary to lock the sliding lid closed.

The sides of the drawers are veneered, at the front, with trellis marquetry, and the writing surface that slides back to reveal compartments sits on ebony glides. The marquetry is relatively unfaded, and the brightness of the trellis gives some idea of the original appearance of the table. The interior of the drawer is divided into two compartments of unequal size, completely lined with pale blue watered silk (fig. 19-2).

Figure 19-2

Figure 19-2Marks

The underside of the table on the rear rail is stamped “J.F.OEBEN” twice (fig. 19-3). The underside of the central rail is inscribed with “No.4” in ink. Also beneath the table is a label printed “Mrs. John D. Rockefeller, Jr. / 10 West Fifty-fourth Street, New York.” A label inside the drawer in the front right compartment is inked, “C.6478 / J.D.R Jnr.”

Figure 19-3

Figure 19-3Commentary

In his short career, Oeben made numerous small toilette tables that contained mechanical fittings or were designed to be manipulated by hand.1 The Museum’s table, stamped “J.F.OEBEN,” is of the latter variety: when the large drawer in the frieze is unlocked the drawer can be pulled out by hand and the top slid back. These toilette or writing tables were decorated with floral marquetry, sometimes combined with geometrical parquetry as seen on this example.2 Examples are known that are solely veneered with parquetry3 or with plain veneers.4

Two other tables bear trellis marquetry of the same design, with similarly decorated tops containing the four animals that represent the elements. One is in the musée du Louvre,5 and the other, formerly in the Lindenborg family, was sold in Paris in 2003 (figs. 19-4, 19-5).6 The top of the former table shows a basket of different form, but some of the flowers that fill it have been cut from the same patterns or templates as those on the Museum’s table. The surrounding frame is of differing design, and the floral swags are composed of flowers that are more widely placed, though many are of the same model.7 The table from the Lindenborg collection, probably the one purchased in Paris in 1768 by the Heinrich Carl von Schimmelmann, has a marquetry top of almost precisely the same design as that found on the Museum’s table. With the exception of the large tulip, the flowers in the central basket repeat each other, as do those composing the floral swags.8

Figure 19-4

Figure 19-4 Figure 19-5

Figure 19-5This reuse and repetition of elements is also found in the floral marquetry of André Charles Boulle, in whose steps Oeben followed in his reintroduction of naturalistic floral marquetry on Parisian furniture. Oeben would have been familiar with that great master’s work, especially as he rented lodgings at the Louvre in the large apartment of Boulle’s youngest son, Charles Joseph. He lived there from 1751 to 1754. In the inventory taken after Oeben’s death on January 21, 1763, the following is listed on March 3: “Un petit coffre-fort remply de fleurs en bois découpé et nué, propres à être employés en différens ouvrages, dont la plus large est d’environ 3 au 4 pouces et la plus petite de la largeur de 3 lignes.”9 A similar box containing wood flowers and birds was listed as being destroyed in the fire of 1720 at André Charles Boulle’s workshop.10

Unlike the Museum’s table, the two other similar examples are fitted with small drawers set within the large frieze drawer. This addition necessarily makes the drawer quite shallow in the central area. The drawer of the Louvre table has a central rectangle decorated with Japanese lacquer that lifts to form a reading stand. It is flanked on either side by lidded compartments. The surfaces of the lids are veneered with the same design of trellis marquetry as that found on the frieze. The interior of the drawer of the Lindenborg table is fitted with, at the center, a covered compartment, the lid of which slides back. To either side the hinged lids of the compartments are veneered with marquetry depicting single-cut branches of roses.

The large single drawer of the Museum’s table is not fitted with a bookrest or lidded compartments. The entire lidded surface, at pressure on a button, can be released and pushed back manually to reveal a blue silk–lined interior. The trilobed panel of leather forming a writing surface has been stained to resemble marble, and the gilded tooling around the edge may be original. Such a sliding arrangement is unique in Oeben’s oeuvre, although a shaped and similarly stained leather panel, decorated with a border of tooled and gilded daisies, is found on the inner surface of the fall front of a small writing box stamped with this master’s name.11

These three tables have been traditionally dated to 1754 or a little earlier on the basis of a table of similar form and decoration that appears in a painting by François Guérin (active between 1751 and 1791) of Madame de Pompadour and her daughter Alexandrine Le Normant d’Etiolles, formerly in the Edouard de Rothschild collection. The table in the painting is shown open, with the sides of the drawer veneered with no design but with the surfaces of the hinged lids decorated with trellis marquetry; this is likely to be the one now in the musée du Louvre, whose trellis pattern on its sides also corresponds to what is visible on the profile view of the table in the double portrait.12 Alexandrine died in 1754 of peritonitis, and previous historians have used this date as the last possible year for the execution of the painting and the table depicted in it. However, Alastair Laing has discovered that the painting was described in the Salon of 1763 and is a posthumous portrait of the child, apparently taken from a painting made by François Boucher in 1749.13 Thus it is known that Madame de Pompadour possessed a table of this type in 1763, but it is not known when she acquired it, nor can it be identified in the inventory taken at her death a year later. Similar identification issues arise for the exceptional Oeben table from the Jack and Belle Linsky Collection preserved in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. With its flower marquetry on the sides and its unique treatment of the legs, pierced with three openings, it does not match the table in the Guérin painting. Nonetheless, it was most likely made for Madame de Pompadour, whose coat of arms appears in the gilt bronze mounts at each corner and whose ducal coronet decorates the vase at the center of the marquetry top (in 1752 she was given the title duchesse-marquise de Pompadour). But neither can the Linsky table be identified with the ones cited in the after-death inventory of Madame de Pompadour.14

The dating of objects made by Oeben is extremely difficult as his entire career lasted only about sixteen years. After his death in 1763, his widow, per guild regulations, continued operating the workshop with his stamp. It is very likely that a considerable number of pieces in the neoclassical style bearing Oeben’s stamp were in fact made or finished after his death. One former apprentice, Jean-Henri Riesener, took over the practical day-to-day production of the workshop, married Oeben’s widow in 1767, and continued to use his master’s stamp at least until he himself became a master in 1768.

Oeben’s name first appears in the Livre Journal of Lazare Duvaux in 1752, where he is listed four times as making a total of twelve frames, some listed as for prints and others listed as being in “bois de rapport, à fleurs” or “incrusté de fleurs,” that were all sold to Madame de Pompadour. Between 1757 and 1758 five mechanical tables are listed in the Livre Journal.15 None is entered under Oeben’s name, and only one is described as having floral marquetry. That table cost 216 livres, as did three of the others, so it should be assumed that they were similarly decorated.

At least four tables coulantes or à coulisse are listed in the inventory taken at Oeben’s death, and three other tables are described in some detail.16 One, with almost the same measurements as a larger table in the Rijksmuseum,17 appears in the chambre of the late Oeben:

Une table de 3 pieds 4 pouces [108 cm] de long sur 19 pouces [51 cm] de large, 27 pouces [72 cm] de haut, plaquée sur le dessus de bois de rose à compartiments et filets blancs et noirs, trois panneaux sur le dessus fond d’amaranthe incrustées de fleurs nuancées, le corps de la parclose au pourtour en mosaïque de rose bleu fond satiné, orné de quatre chutes de bronze ciselé à testes de bellier doré d’or moulu et petites moulures sur tous le champs, le dessus orné d’une moulure de bronze au pourtour d’un pouce [2.7 cm] de large, le tout doré d’or moulu, le dessus s’ouvrant à ressorts secrets avec son pupitre avec ses pieds chausés à roulettes de cuivre.18

The table was valued at 700 livres. The two other tables, described as being in the magasin “ayant vue sur le Cour du Prince,” are listed as follows:

1. Item, une table en pupitre, de 32 pouces [86 cm] de long sur 26 [70 cm] de large et 16 [43 cm] de profondeur, le dessus de bois argenté garni de fleurs, et le pupitre de bois de rose et deux panneaux de fleurs, [lids for compartments?] le dessus de lad. table garnie de sa moulure de bronze - prisée 96 liv[res].19

83. Item, une table coulante de 27 pouces [72 cm] de long, 16 pouces [43 cm] de large, avec un tiroir par le côté, plaquée en mosaique, ornée de chutes, pieds, cadre autour du dessus et moulures autour de la parclose de bronze non doré - prisée 96 liv.20

Both of these tables, bearing measurements similar to the Museum’s example, were being offered for sale and must have been made in the last year or two before Oeben’s premature death. As in 1757 he was probably the supplier to Lazare Duvaux of such tables, he must have produced this popular model at least during the last six years of his life. Oeben specialized in small tables with mechanized moving parts, though the Museum’s table did not and does not have such a mechanism: the moving parts were and remain manually operated. Even so, the carcass of the Museum’s table may have been made by Oeben in the early 1760s, while the veneer, with its somewhat neoclassical trellis marquetry, was most likely applied by his workshop after his death in 1763.

The marquetry on the top of this table uses very little veneer dyed with the problematic, blackening green dye seen in cat. no. 17 and discussed at length in cat. no. 18. Oeben seems to have used his inherently flawed green dye extensively in the mid-1750s when he introduced this form of table, and the majority of floral marquetry produced in his lifetime contains substantial numbers of dark brown or black leaves and stems that are the result of the deterioration of the components of this dye recipe. The poor stability of the greens dyed with this recipe must have become apparent within a decade or two, and its use diminished over time. Thus the very limited use of blackened wood in the Museum’s table argues for a date of the marquetry in the 1760s.

As is the case with most ébénistes of the eighteenth century, no working drawings or sketches made in Oeben’s workshop have survived. His floral marquetry has been compared to the engravings after the flower painter Louis Tessier (ca. 1719–1781) who worked in the Gobelins at the same time as Oeben. Indeed, the families appear to have been close, for in 1768 a daughter of Tessier became godmother to a daughter of Simon Oeben.21 Flowers based on designs after Tessier appear in the marquetry of Oeben on several pieces.22 They also appear on pieces attributed to Jean-Pierre Latz and even in the marquetry of pieces by Oeben’s apprentice, Jean-Henri Riesener.23 The direct and indirect transmission of Tessier’s flower patterns to the workshop of ébénistes deserves further study.24 A technical examination of this table shows that the marquetry was cut using the conic cutting method, which succeeded the knife inlaid method characteristic of work produced by Oeben, as, for instance, the other Museum’s table (cat. no. 18) (see “Technical Description” below).

Francis Watson has pointed out that the trellis pattern used by Oeben for the friezes of at least these three tables seems to derive from similar trelliswork found in lacquer on the drawer fronts of Japanese boxes (kodansu).25 This design, a traditional Japanese pattern, was found on lacquered objects imported into France in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. It is possible that a marchand-mercier such as Lazare Duvaux who sold such exotic wares might have encouraged Oeben to adapt the design to his marquetry.

The gilt bronze mounts on the Museum’s table are of the same model as those found on the two similar tables mentioned above (Louvre and ex. coll. Lindenborg). The scrolled feet are found on numerous mechanical tables by Oeben, as are the corner mounts bearing the masks of mustachioed Chinese men.26 The names of the craftsmen who supplied them are listed in the inventory taken at Oeben’s death in 1763.27 He owed the chaser Louis Barthélemy Hervieux the large sum of 7,721 livres, showing that the latter must have provided a great amount of work for the master.28 To the chaser Duplessis29 and the caster Étienne Forestier30 he owed 1,122 livres and 4,179 livres 9 sols 3 deniers, respectively.

Provenance

Before 1912: John George Stewart Murray, Marquess of Tullibardine, eighth Duke of Atholl, Scottish, 1871–1942 (Scotland), sold or by gift to Mary Gavin Baillie-Hamilton;31 before or by 1912: Mary Gavin Baillie-Hamilton (Hon. Mrs. Robert Baillie-Hamilton), Scottish, 1832–1912, by gift or inheritance to her sister Magdalen Bateson Harvey;32 by 1912–13: Magdalen Bateson Harvey (Lady Harvey), Scottish, 1836–1913 (London, England);33 by 1913 and before 1927: Lewis & Simmons (180 New Bond Street, London, England; 16, rue de la Paix, Paris, France; and 605 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY), sold to Elbert H. Gary;34 –1927: Elbert H. Gary, American, 1846–1927 (New York, NY), upon his death, held in trust by the estate;35 1927–28: Estate of Elbert H. Gary, American, 1846–1927 [sold, Collection of the Estate of the Late Judge Elbert H. Gary, American Art Association, April 21, 1928, lot 272, to Duveen Brothers, Inc.]; 1928: Duveen Brothers, Inc. (New York, NY), sold to John D. Rockefeller, 1928;36 1928–60: John D. Rockefeller, Jr., American, 1874–1960 (New York, NY), by inheritance to his wife, Martha Baird Rockefeller, 1960;37 1960–71: Martha Baird Rockefeller, American, 1895–1971 (New York, NY) [sold, Property of the Estate of the Late Martha Baird Rockefeller, Parke-Bernet Galleries, New York, October 23, 1971, lot 712, through the Antique Porcelain Company to the J. Paul Getty Museum].38

Exhibition History

The J. Paul Getty Collection, Minneapolis Institute of Art (Minneapolis), June 29–September 3, 1972; The J. Paul Getty Collection of French Decorative Arts, Detroit Institute of Arts (Detroit), October 3, 1972–August 31, 1973; The Making of Furniture, J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Center (Los Angeles), October 7, 2003–October 23, 2005.

Bibliography

, unpaginated, no. 56, ill. 61; , 111, ill.; , 619; , 255, fig. 264; , 52, no. 67; , 169, fig. 12; , 55, fig. 5; , 256, fig. 11; , 31, 148–53, ill.; , 12–13, cover, ill.; , 36–37, no. 64; , 96–97, 182, ill.; , 106–7, fig. 134; , 177, 179; , 386.

- G.W.

Technical Description

The table’s structure is constructed entirely of oak. The four cabriole legs are made from single pieces of oak, extending from the floor to the top of the case. The serpentine side and back rails of the case are built up of four glued laminations of plain-sawn oak, stacked one on top of the other. Each lamina is approximately 3.3 cm high, corresponding to 1 1/4 Paris pouce, and is carefully positioned with the growth rings oriented horizontally such that the assembled rail is effectively quartersawn. This refined method of assembly yields rails of optimal dimensional stability. The side, front, and back rails are attached to the legs with unpegged, shouldered mortise-and-tenon joints, clearly visible in X-radiographs. The front rail is made of a single heavy piece of oak, which is connected to the two front legs with paired mortise and tenons, also unpegged. The front edge of this rail has been carved back, or relieved, at the sides to accommodate the pendant brackets along the lower edge of the drawer front.

The table’s top is made of three pieces of perfectly quartersawn oak, butt joined and glued together. The top slides forward and back on paired brass rails, mounted with iron screws to the case sides and to the underside of the top. The brass runners are neat and tight in the case sides, though the runners on the top are not. It seems that repairs to the top addressing shrinkage problems required that the runners be slightly repositioned and the mortises expanded. The runners are cast, not made from sheet brass, as is made clear by significant porosities visible in the metal. The movement of the top is limited by stop pins that run through the side rails from bottom to top near the back leg. The tops of the pins run in grooves cut into the underside of the top; they are roughly threaded along their lower inch, near the slotted heads (fig. 19-6). This threading is designed to grab the wood of the case-side hole, but after centuries of use, the holes are nearly completely stripped. The lack of a spring-powered, or even geared, opening mechanism makes this table unusual among the many similar tables à coulisse produced in Oeben’s workshop. This feature is, however, shared with the Lindenborg table, thought to have been purchased in 1768 and which has a nearly identical marquetry design.

Figure 19-6

Figure 19-6The case bottom is formed of two panels, each made of two pieces of quartersawn oak, butt joined and glued to each other, and separated by a medial rail running from the center of the front rail to the center of the rear rail (fig. 19-7). The medial rail, which is chamfered along all four longitudinal edges, is fastened to the rails on either end with unpegged mortise-and-tenon joints. The two panels rest in grooves cut into the side rails, legs, and medial rail and front and rear rails. The grain of the panels runs from side to side, and the panels are not beveled on either face. The internal drawer runners were glued in place after the assembly of the case bottom.

The drawer unit, with its sliding writing surface, rides on ebony glides approximately 1 cm square, which are glued into a groove in the drawer side (fig. 19-8). These glides slide in grooves in the case sides, running from the rear of the case interior to the very front surface of the case. At their forward end, these grooves are hidden, and the forward travel of the drawer unit is stopped by diagonally positioned blocks of tulipwood, which slide into a tapered dovetail mortise in the front face of each leg (fig. 19-9). The blocks are held in place and are hidden by the bronze mounts on the corners.

Figure 19-8

Figure 19-8 Figure 19-9

Figure 19-9The sides of the drawer unit are made of quartersawn oak boards. The curved front and rear panels are fabricated in a manner analogous to the case sides and back, with three plain-sawn boards glued one atop the other and then sawn to shape, resulting in a dimensionally stable quartersawn element. The drawer bottom is composed of four pieces of quartersawn oak, butt joined, with the grain running from side to side. The bottom slides into grooves in the drawer sides from the rear, overlapping the drawer back. The drawer is divided in its interior by an oak board running from front to back near the right side, held in place with rabbet-and-dado joints at either end. The lining of the drawer is a plain weave, moiré silk textile, trimmed so that no selvage is visible and glued to the substrate with an unknown adhesive. The threads, which exhibit little or no twist, are woven finely, with 39 threads per cm along the warp and 43 threads per cm along the weft.

The sliding writing surface is made of four quartersawn oak panels, butt joined and glued together, with the grain running from side to side. The panel slides into the drawer assembly from the rear, running in grooves in the sides of the drawer. This relatively thin panel was not counter-veneered and, perhaps as a result, has cupped slightly.

The elaborate veneering of the table utilizes a wide variety of naturally colored and dyed woods, executed in a combination of saw- and knife-cut techniques. The floral marquetry of the top is executed in a variety of natural and dyed woods that could only be identified by direct observation under magnification, without sampling for anatomical investigation by thin section (as is preferred). Without microscopic examination of anatomical features, the identification of the woods must be considered provisional, but the top appears to contain kingwood, amaranth, bloodwood, barberry, boxwood, holly, maple burl, hornbeam, and sycamore maple. Many of the flowers are made from a single piece of wood, with the contrast and shadows provided by careful sand shading and the use of carefully selected figured wood such as end-grain and oyster-cut barberry veneer.

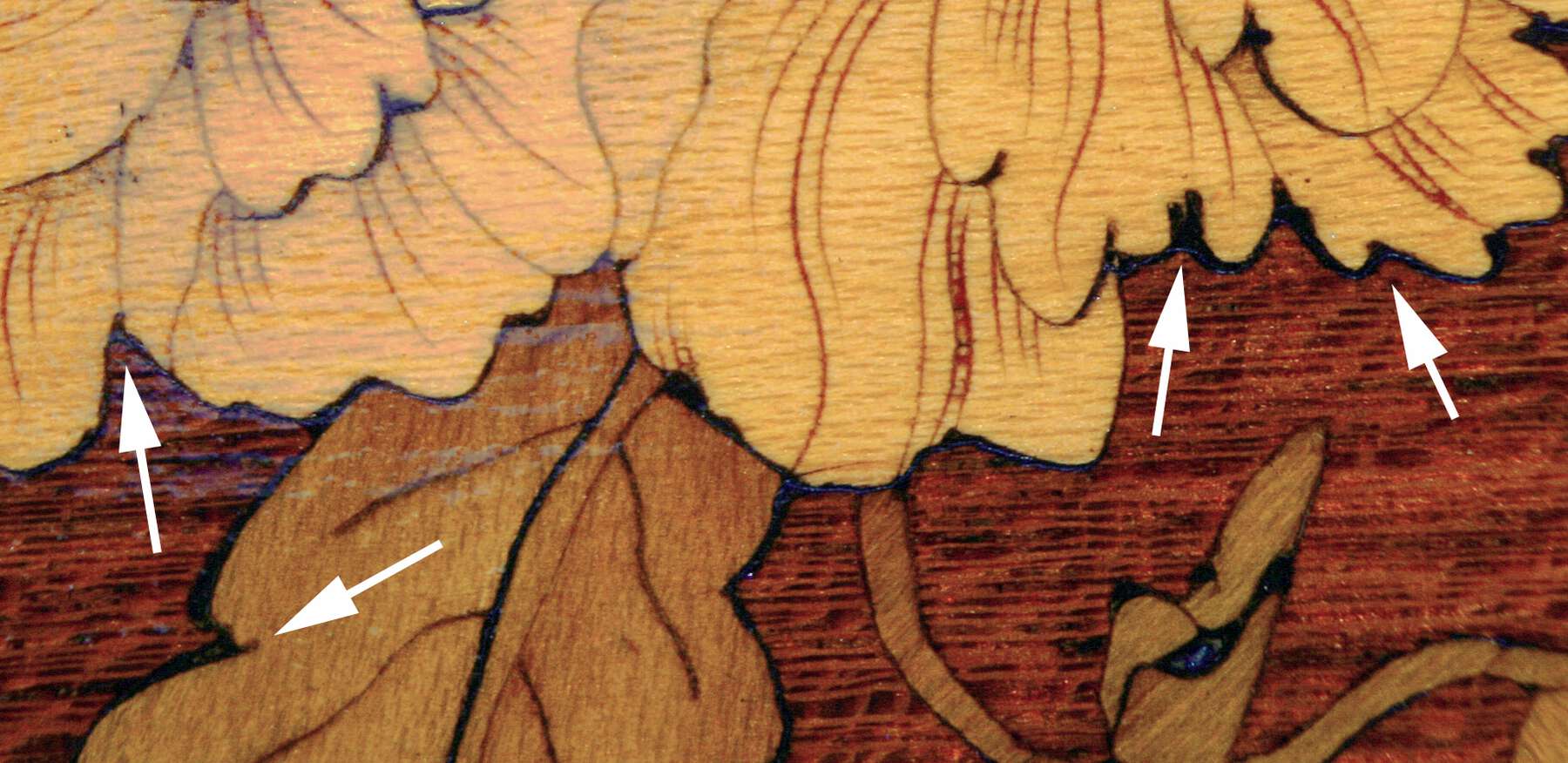

Careful examination of the marquetry under magnification, in combination with X-radiography, reveals certain information about the working methods used. It appears that nearly all the flowers and a majority of the leaves on the table’s top were stack cut using a fretsaw, mostly from single pieces of naturally colored or dyed veneer. The individual elements of each flower were selectively sand shaded to give the illusion of shadow and volume and then reassembled, closing up the gaps or kerfs made by the saw as much as possible, before gluing them to pieces of paper. The flowers and many of the leaves appear to have been inlaid in the amaranth veneer background using a fretsaw, before the amaranth was glued down to the oak substrate. The evidence for this is found by a careful examination of the perimeters of the elements; both the flowers and the leaves tend to have rounded forms, with few pointed tips, and the blunt-ended kerf left by the saw blade is often visible at inner corners (fig. 19-10). The gap between the flowers and the background is larger than it is for the shoulder-knife inlaid flowers in Oeben’s earlier marquetry (cat. nos. 17, 18) but is thin enough in many instances to suggest that the flowers may have been inlaid using a specialized sawing technique known as bevel cutting or conic cutting. The process is similar to boulle marquetry or stack cutting where the flower or leaf is glued to the background veneer and the outline is cut simultaneously in the flower and the background veneer. However, unlike boulle marquetry cutting, in conic cutting the saw blade is angled slightly away from the center of the flower during cutting so that the flower is slightly enlarged and the corresponding hole in the background is slightly reduced. This has the effect of nearly eliminating the kerf created by the saw blade when the flower is glued in place.39 When executed well, this technique results in very tight joins; however, only a single inlay group can be made at a time. Knife marks and bent fibers, which are the signs of shoulder knife inlaying, are limited to the stems of the flowers and a few leaves on this table (fig. 19-11).

Figure 19-10

Figure 19-10 Figure 19-11

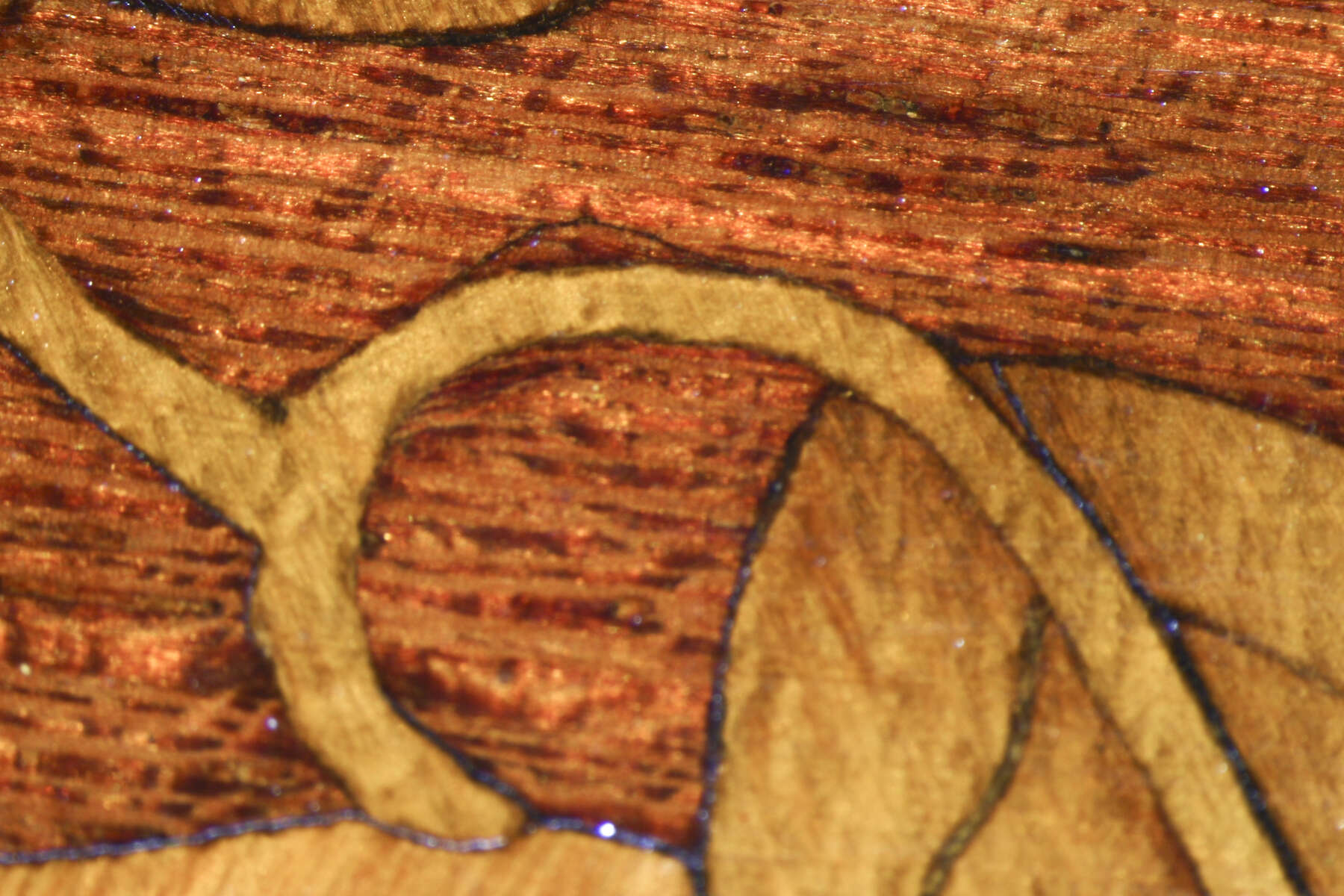

Figure 19-11Examination of the marquetry on the top using X-radiography supports the conclusion that the flowers were saw inlaid first, presumably by conic cutting, and that the stems were inlaid after the flowers and background veneer were already adhered to the oak substrate. In figure 19-12, the outlines of the flowers and stems are visible because animal glue, concentrated in the joints, is denser and more radio-opaque than wood, resulting in a white line in the X-radiograph. The lines between the flower petals and the background veneer are notably less distinct than the lines surrounding the pieces of stem. This is almost certainly because the stems were inlaid using a shoulder knife, which cut through the background veneer into the oak substrate, leaving a deep mark. When the stems were glued in place, the knife mark filled with glue, resulting in a thicker glue line than around the saw-inlaid flowers. In addition, the knife marks around the stems do not continue under the flowers, which accords with the stems being inlaid after the flowers. This is in contrast to what is seen in the X-radiographs of the marquetry on the top of Oeben’s earlier mechanical table (see fig. 18-18), where the cut marks of the stems are clearly visible under the flowers, showing that the stems were inlaid first, followed by the flowers.

Figure 19-12

Figure 19-12The differences in marquetry technique between this table and the mechanical table (cat. no. 18) suggest that this table was produced later. In particular, conic cutting (more evidence of which below) is generally considered to have been developed in the later Rococo period and represents an innovation in technique that succeeded the use of shoulder knife inlay, used by Oeben in the 1750s and early 1760s.

Much of the hornbeam and sycamore maple, which, along with the naturally bright yellow barberry, comprises the majority of the floral elements, is likely to have been dyed in shades of green, blue, and red, though only vestiges of blue and green remain visible today. Traces of a bluish-green color survive in the maple burl wood panels that were likely dyed in imitation of stone.40 The small leaf elements, which currently appear black, are probably holly that was originally dyed olive green but has degraded due to the high iron sulfate content of the dye recipe (see cat. no. 18). As mentioned in “Commentary” above, the very limited use of this deterioration-prone dye recipe on this tabletop suggests a relatively late date for the marquetry. As points of comparison, the toilette and writing table at the Wallace Collection (inv. F110), thought to have been completed in Oeben’s workshop in 1763 or 1764, still made extensive use of this now-darkened wood in the central floral marquetry of the top, while the Lindenborg table, thought to have been purchased in 1768, appears to use even less than the Museum’s table. Unfortunately, at the time of writing, the location of the Lindenborg table is not known, so it has not been possible to examine it in person to make precise comparisons of the marquetry pattern and cutting techniques.

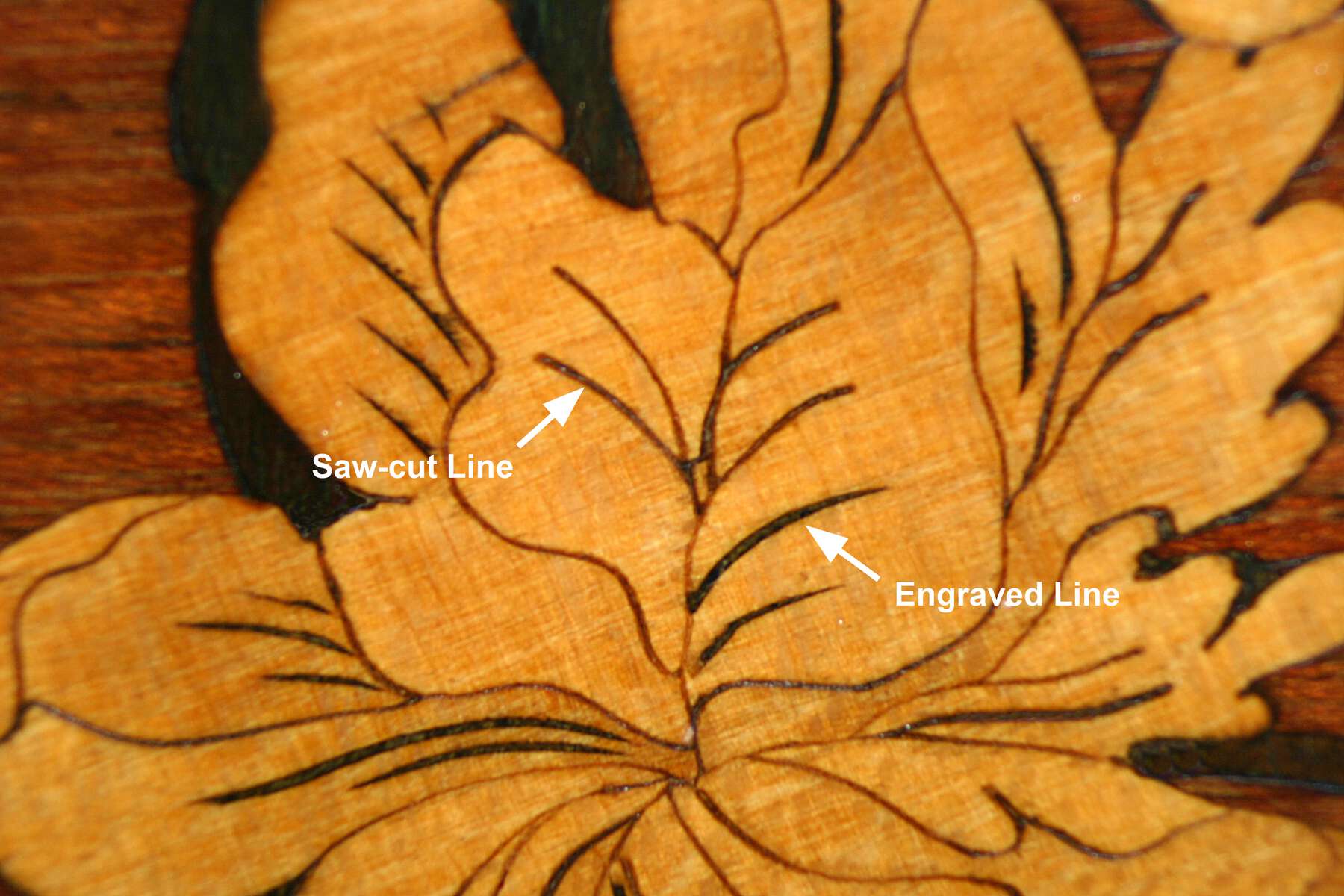

There is some limited engraving visible in the marquetry of the top. This is clearly distinguishable from saw cuts under magnification as the engraved lines end in sharp points while saw-cut lines have a blunt, square end (fig. 19-13). The engraving occurs primarily in the four animals representing the elements, though two clusters of flowers are also engraved; on one of these clusters the lines are colored with a red-pigmented filler, almost certainly containing vermilion based on the detection of mercury by X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF).

Figure 19-13

Figure 19-13The sides of the case and the drawer unit are decorated with geometric marquetry in tulipwood, amaranth, holly, barberry, black-dyed holly or maple, and green-stained maple burl. Every visible interior surface of the compartment beneath the writing surface has been very carefully veneered with tulipwood so that the oak substrate is not visible.

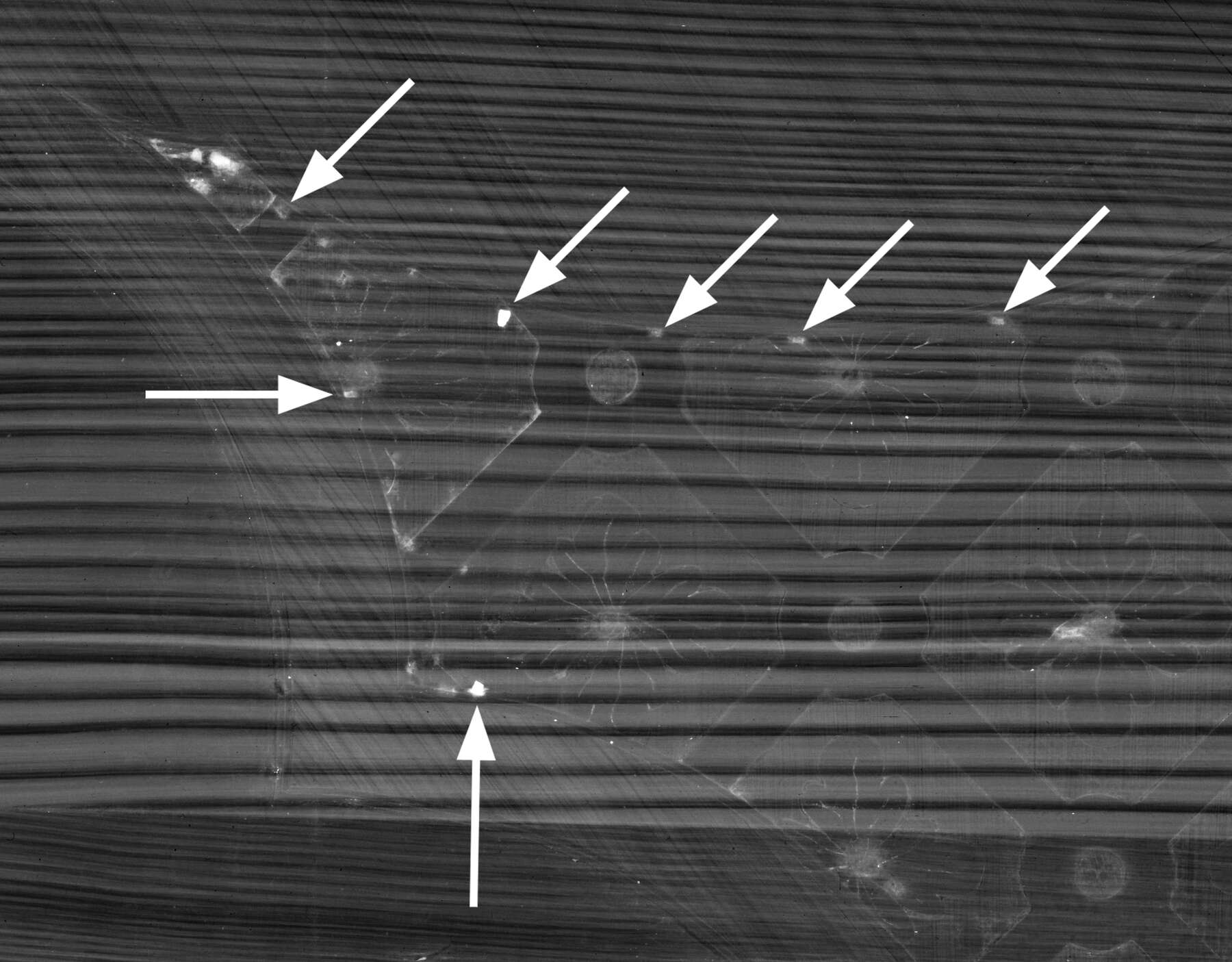

Based on evidence revealed by careful visual examination of the marquetry, augmented by X-radiography, it is likely that the trellis marquetry on the sides of the table was cut using a combination of fretsaw cutting and inlay using a shoulder knife. By examining X-rays of the marquetry on the case sides and writing surface, it was possible to determine that the tulipwood border was laid down first and the holly and black-dyed maple stringing was then glued in place along its borders. During assembly, the stringing was held in place with small veneer pins, nailed into the oak substrate, which pushed the thin strips of wood up against the edge of the tulipwood. The holes left by these pins, and even some of the tips of the pins that broke off in the wood, were then covered when the adjacent trellis marquetry was applied. This evidence is now visible in X-ray images (fig. 19-14).

Figure 19-14

Figure 19-14It seems that the holly framing of the trellis was applied next. The general shape of the trellis was apparently cut first using a fretsaw, but following gluing of the trellis on the carcass, it was trimmed to final shape with an inlay knife. Saw cut marks (fig. 19-15) as well as inlay knife marks (fig. 19-16) are both visible on the white holly trellis; however, the most obvious fretsaw mark is approximately 2 mm from the finished trellis edge, so it can be concluded that the fretsaw was used to cut the trellis to an approximate size and that it was adjusted, after gluing, with a shoulder knife.

Figure 19-15

Figure 19-15 Figure 19-16

Figure 19-16The barberry flowers set in amaranth fields were the last elements to be added to the trellis parquetry. These flowers appear to have been inlaid using the same conic cutting technique as was used for the flowers on the top, though in this case the evidence for angled saw cutting is much clearer. Again, the flowers were produced as individual pieces by cutting them out with a piercing saw. While all of the flowers are of the same general form, there is considerable variation among flowers in the shape of the petals, indicating that they were cut quickly, without following a precise pattern. Some flower elements were shaded by leaving individual pieces of veneer to heat in hot sand until the desired level of singeing was obtained. Again, the elements forming each flower would have been drawn together into the flower shape and glued to a paper backing, largely eliminating the kerfs left by the saw blade. Once cut and assembled, the flowers were inlaid in the amaranth background using a fretsaw. A cross section of the trellis marquetry is visible on the edge of the internal sliding writing surface. It clearly shows an angle to the edge of the barberry flowers, an indication that the flowers were set in the purpleheart with a bevel for a perfect fit (fig. 19-17). While such bevel angles are also possible where an inlay knife has been used, in view of the other supporting evidence, it seems clear that conic cutting using a fretsaw was employed in this instance.

Figure 19-17

Figure 19-17The small, round amaranth plugs or dots set in the white trellis are very uneven in shape, and careful observation of the holly trellis shows that the holes to receive the amaranth plugs in the trellis were not drilled, as one might expect, but were cut out using an inlay knife. This time-consuming and arguably not very successful technique is unusual for the workshop of Oeben/Riesener.

It is difficult today to appreciate how colorful this marquetry would have been when first made. Computer reconstructions41 and modern marquetry reconstructions offer interesting suggestions of what the marquetry of this table may have looked like, but the intensity and hue of the color for dyed woods in particular remains somewhat speculative. Since the trellis marquetry of the case sides is done entirely in naturally colored woods, a quite clear idea of its original appearance can be gained by faithful reproduction. A didactic reproduction, made in 2003 by Alain Guéroult under the supervision of Michel Jamet (L’Ebénisterie Michel Jamet, Paris), conveys a very realistic impression of the original vibrant color and contrast of this marquetry (fig. 19-18).

Figure 19-18

Figure 19-18The marbleized leather writing surface and the elaborate gilt tooling appear to be original. The leather appears to be sheepskin based on the triplet clusters of hair follicles, arranged in wavy bands. The coloring technique seems to correspond in general to Guffecourt’s 1763 description of “grosse marbrure . . . pour quatre couleurs” (large marbling in four colors),42 except that in this case there appears to be a fifth color (fig. 19-19). The dominant pattern of the marbling is executed in two tones, a greenish-gray and a black stain. Both of these are presumably achieved using iron-containing solutions of different strengths. Gauffecourt’s recipes call for solutions prepared by soaking iron filings in vinegar, possibly with the addition of lemon juice. It is also possible that iron sulfate solutions (vitriol vert) may have been used. Accents of red have been added, apparently using one more concentrated and one more dilute stain of the same red dye material. Gauffecourt calls for the red accents to be achieved with brazilwood, using an alum mordant, though no analysis has been carried out on this leather to confirm the dye material. The fifth color present in this leather, which is not described by Gauffecourt, is a transparent green with blurred edges. This appears in long streaks or veins rather than the hard-edged, globular patterns of the other four colors. The green color appears to have been applied over the other colors but still below the gilt tooling.

Figure 19-19

Figure 19-19The majority of the elaborately tooled gilt border running continuously around the perimeter of the leather appears to have been executed with two tools. A rolling tool would have created the triangle and line pattern at the edge. The pattern of poppies and scrolling foliage was executed with a single elaborate punch that was struck repeatedly in sequence. In contrast to the simple repeats of the border, the four ornamental compositions in the corners of the leather are each made using seven different small stamps, with the result that each composition is slightly different from the others.

Thirteen brass elements from the table were analyzed for alloy composition by XRF. Nine of these elements were gilded bronze mounts, three were rails from the sliding mechanism, and the last was the lock plate. The gilded bronze mounts appear to be cast from moderate-zinc brass alloys, which are consistent with eighteenth-century manufacture. Two of the mounts (the right rear corner mount and the left rear foot) appear different from the others, as the quality of their chasing is markedly lower than that of all the other mounts. The composition of these two mounts is quite similar to the other mounts, however, so there is no implication that they are significantly later. It is possible that they were simply chased by a less experienced craftsman than the other mounts but still in the same workshop, or they may be early (probably eighteenth-century) replacements.

As expected, the sheet brass of the lock is of a very different alloy than the cast brass of the mounts, with significantly higher zinc levels (about 32%) and relatively low levels of tin, iron, silver, and antimony. This composition can be considered typical of high-quality eighteenth-century sheet brass. The brass rails were cast from an intermediate alloy, with relatively high zinc levels (about 27%) but with levels of other impurities, including lead, similar to the cast mounts. The textile lining over the lock has been cut, lifted, and reglued in order to allow access to the lock. This was done poorly and has resulted in staining of the textile. The lock appears to have been removed for repair but not replaced. There is only one set of screw holes in the substrate, and the position of the keyhole has not been altered.

There does not appear to be any original varnish or wax on the table. At present there are at least two layers of varnish; based on examination under ultraviolet light, the lower varnish appears to be shellac based. This has been sanded through in some areas. On top of the shellac layer, a bluish-white fluorescing synthetic varnish has been applied.

- A.H.,

- Y.C.,

- C.E.,

- and K.P.

Notes

For information on Jean-François Oeben, see , 252–63; . ↩︎

, figs. on pp. 17, 95, 101, 119, 124, 125. ↩︎

, 29, 93, 95, 131, 133. ↩︎

, 95. ↩︎

Inv. no. OA 10404. , 176–79, cat. no. 53. H: 68.3 cm, W: 79.5 cm, D: 44.8 cm.; , 386–87. ↩︎

Sotheby’s, Bel ameublement et objets d’art, December 15, 2003 (Paris: Sotheby’s, 2003), no. 109. H: 72 cm, W: 80 cm, D: 43 cm. None of the contributors of this entry has seen that table personally or knows of a furniture specialist who could examine it. ↩︎

Schematic engravings of the tops of the tables in the Louvre and in the J. Paul Getty Museum are illustrated in , 148–53. Ramond identifies the woods used and discusses the quality of the marquetry. ↩︎

, 81–88; , 119; , 174–77. A table in the Rijksmuseum (acc. no. R.B/.K.16662) has a basket filled with flowers of the same form as those on the Museum’s table. Extra branches of rosebuds and honeysuckle leaves have been added to the left and right to fill larger areas caused by the greater width of the table (105 cm). ↩︎

, 298–367, esp. 356 (Paris, Archives nationales de France, Z/1m 39). ↩︎

Inventory drawn up by Boulle after the fire: , 347. See also , 121. ↩︎

Formerly in the possession of Kraemer, Paris, per undated catalogue. ↩︎

I thank Arlen Heginbotham and Yannick Chastang for these observations. Indeed, the table seen in profile in the painting is shown with a corner that has a marquetry pattern with one or two lozenges vertically aligned, as in the Louvre table, while the pattern of the Museum’s table in the corner, next to the legs, is larger, with two or three lozenges vertically aligned. ↩︎

Alastair Laing shared his discovery with Xavier Salmon, who refers to it in , 156–57, fig. 2. ↩︎

It should be added that it cannot even be identified in the inventory prepared after Oeben’s death, either in the list of items awaiting delivery to Madame de Pompadour or in his large stock of completed and partly completed furniture. On this table, see William Rieder, in , 150–52, cat. no. 60, figs. 87, 88. ↩︎

, 334–35, October 12, 1757: “2896.–Mme la Ctesse de MAUREPAS: . . . une table à écrire à tiroir, le dessus qui se pousse, en bois de rose, avec garnitures & portans dorés d’or moulu, 216 l.”; 349, June 25, 1758: “3041.–M. de la REYNIÈRE; une table à écrire dont le dessus à coulisse, le tiroir garni de quarts de rond, baguettes, pieds, chûtes & ornemens dorés d’or moulu, le placage en bois de rose à fleurs, 216 l.”; 352, February 2, 1758: “3057.– M. le Cte d’Usson. . . . Une table à écrire dont le dessus est à coulisse, plaquée en bois de rose, les ornemens dorés d’or moulu, 192 l.”; 368, June 9, 1758: “3165.– Mme la Duchesse de MAZARIN: . . . une table à écrire à coulisse, tiroirs & écritoire en bois de rose & ornemens de bronze doré d’or moulu, 216 l.”; 371, July 27, 1758: “3189.–M. de BOULOGNE, fils: . . . une table à écrire à coulise, plaquée en bois, garnie en bronze doré d’or moulu, 216 l.” ↩︎

, 330–38: No. 4–“une petite table à coulisse”; No. 8–“une table à coulisses, plaquée en bois d’acajou de 3 pieds [97 cm] de long, 16 pouces [43 cm] de large, garnie d’une tablette dans l’entre jambe et une moulure de bronze non doré au pourtour du dessus”; No. 47–“une table coulante”; No. 82–“une table dont le dessus est à coulisse.” ↩︎

Rijksmuseum acc. no. BK-16854; , 178–81; , 119. ↩︎

, 328. ↩︎

, 329. ↩︎

, 338. ↩︎

, 132. ↩︎

The Tessier engraving of a lily is reproduced in , vol. 1, 245. For the appearance of the lily in Oeben marquetry, see , a secrétaire on p. 73 and a mechanical table with tiers of drawers to either side of a kneehole on pp. 120–21 (cat. no. 155). ↩︎

For lilies in the marquetry on pieces attributed to Jean-Pierre Latz, see the corner cupboard 72.DA.39.2 in cat. no. 17; and for those in the marquetry of Jean-Henri Riesener, see a commode delivered to the comtesse de Provence in 1776, illustrated in , vol. 1, 244; and on the surface of a table delivered to Madame Elisabeth in 1778, see , vol. 2, 512. ↩︎

, vol. 1, 307; . ↩︎

, 157–66. ↩︎

, 25, 29, 93, 132–33. ↩︎

, 298–367 (Paris, Archives nationales de France, Z/1m 39). ↩︎

, 301, under no. 7; , 28; , 262–63. ↩︎

, 301, under no. 10; , 28; , 263. ↩︎

, 308, under no. 66; , 28; , 263. ↩︎

Collection of the Estate of the Late Judge Elbert H. Gary, American Art Association, April 21, 1928, lot 272: “Collection of Mrs. Mary Gavin Baillie Hamilton”; Getty Research Institute, Photo Archive, Seligmann Collection, 89.P.7, box 15. The identity of the marquess is based on the fact that he only had this title until 1917. ↩︎

Collection of the Estate of the Late Judge Elbert H. Gary, American Art Association, April 21, 1928, lot 272: “Collection of Mrs. Mary Gavin Baillie Hamilton”; Getty Research Institute, Photo Archive, Seligmann Collection, 89.P.7, box 15. ↩︎

Collection of the Estate of the Late Judge Elbert H. Gary, American Art Association, April 21, 1928, lot 272: “Collection of Lady Harvey, London”; Getty Research Institute, Photo Archive, Seligmann Collection, 89.P.7, box 15. ↩︎

Collection of the Estate of the Late Judge Elbert H. Gary, American Art Association, April 21, 1928, lot 272: “From Lewis and Simmons, Paris”; Getty Research Institute, Photo Archive, Seligmann Collection, 89.P.7, box 15. ↩︎

Ronald Freyberger, “Great Auctions of the Past: The Judge Elbert H. Gary Sale,” Auction 2, no. 10 (June 1969): 10–13. Judge Elbert H. Gary founded U.S. Steel Corporation with J. P. Morgan in 1901. He acquired paintings, sculpture, and decorative art from Duveen beginning in about 1912. A few months before Gary died in 1927 he moved from 856 Fifth Avenue to 1130 Fifth Avenue. His widow decided that everything in the new townhouse should be sold. Duveen offered $1.25 million for the entire collection, but the executors of the estate, the New York Trust Co., decided that the objects should be sold at auction, at the American Art Association. The sale took place in 1928, and Duveen secured the table for John D. Rockefeller, for no cost, for $28,000. , 294–98. ↩︎

Collectors’ files: Gary, E. H., 2, ca. 1927–36, Duveen Brothers Records, Getty Research Institute, 960015, box 455, folder 4; and Collectors’ files: Rockefeller, J. D., Jr., 5, ca. 1926–29, box 505, folder 2; Duveen Brothers Stock Documentation, Getty Research Institute, 2007.D.1, box 516. ↩︎

Collectors’ files: Gary, E. H., 2, ca. 1927–36, Duveen Brothers Records, Getty Research Institute, 960015, box 455, folder 4; Collectors’ files: Rockefeller, J. D., Jr., 5, ca. 1926–29, box 505, folder 2. ↩︎

Ronald Freyberger, “Great Auctions of the Past: The Judge Elbert H. Gary Sale,” Auction 2, no. 10 (June 1969): 10–13. ↩︎

Conic cutting is described in greater detail in , 38–39. ↩︎

For a detailed discussion of the dying and use of burl woods in the seventeenth to nineteenth century, see . ↩︎

. ↩︎

, 44–47, 107–8. ↩︎

Bibliography

- Alcouffe, Dion-Tenenbaum, and Lefébure 1993

- Alcouffe, Daniel, Anne Dion-Tenenbaum, and Amaury Lefébure. Furniture Collections in the Louvre. Vol. 1, Middle Ages, Renaissance, 17th–18th Centuries (Ébénisterie), 19th Century. Dijon: Éditions Faton, 1993.

- Auslander 1996

- Auslander, Leora. Taste and Power: Furnishing Modern France. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996.

- Baarsen 2013

- Baarsen, Reinier. Paris 1650–1900: Decorative Arts in the Rijksmuseum. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, with Rijksmuseum, 2013.

- Baumeister et al. 1997

- Baumeister, Mechthild, Robert A. Blanchette, Jaap Boonstra, Christian-Herbert Fischer, and Deborah Schorsch. Gebeizte Maserfurniere auf historischen Möbeln = Stained Burl Veneer on Historic Furniture. Arbeitshefte des Bayerischen Landesamtes für Denkmalpflege, Arbeitsheft 81. Munich: Lipp, 1997.

- Bremer-David et al. 1993

- Bremer-David, Charissa, et al. Decorative Arts: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue of the Collections of the J. Paul Getty Museum. Malibu, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1993.

- Chastang 2007

- Chastang, Yannick. “Louis Tessier’s Livre de principes de fleurs and the Eighteenth-Century Marqueteur.” Furniture History 43 (2007): 115–26.

- De Bellaigue 1974

- De Bellaigue, Geoffrey. The James A. de Rothschild Collection at Waddesdon Manor: Furniture, Clocks and Gilt Bronzes. 2 vols. Fribourg: Office du Livre, 1974.

- Durand 2014

- Durand, Jannic, ed. Decorative Furnishings and Objets d’Art in the Louvre. Paris: Musée du Louvre, 2014.

- Duvaux 1873

- Duvaux, Lazare. Livre-journal de Lazare Duvaux, Marchand-Bijoutier ordinaire du Roy 1748–1758, vol. 2. Edited by Louis Courajod. Paris: Lahure, 1873.

- Eriksen 1964

- Eriksen, Svend. “Et lille fransk bord.” Virksomhed. Det danske Kunstindustrimuseum 1959–1964 3 (1964): 81–88.

- Gauffecourt 1987

- Gauffecourt, Jean-Vincent Capperonnier de. Traité de la relieure des livres / by Jean-Vincent Capronnier de Gauffecourt; a Bilingual Treatise on Bookbinding. Translated by Claude Benaiteau. Edited by Elaine B. Smyth. Austin: Thomas Taylor, 1987.

- Godla and Hanlon 1995

- Godla, Joseph, and Gordon Hanlon. “Some Applications of Adobe Photoshop for the Documentation of Furniture Conservation.” Journal of the American Institute for Conservation 34, no. 3 (January 1, 1995): 157–72.

- Guiffrey 1899

- Guiffrey, Jules. “Inventaire de Jean-François Oeben 1763.” Nouvelles archives de l’art français, 3rd ser., vol. 15, 298–367. Paris: Noël Charavay, 1899.

- Kisluk-Grosheide, Koeppe, and Rieder 2006

- Kisluk-Grosheide, Daniëlle O., Wolfram Koeppe, and William Rieder. European Furniture in The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Highlights of the Collection. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2006.

- Kjellberg 1989

- Kjellberg, Pierre. Le mobilier français du XVIIIe siècle: Dictionnaire des ébénistes et des menuisiers. Paris: Éditions de l’Amateur, 1989.

- Kopf 2008

- Kopf, Silas. A Marquetry Odyssey: Historical Objects and Personal Work. Manchester, VT: Hudson Hills Press, 2008.

- Montaiglon 1855–56

- Montaiglon, Anatole de. “Incendie du chantier du Sr. Boulle.” Reprint. “Documents sur Pierre et André-Charles Boulle, ébénistes de Louis XIII et Louis XIV.” Archives de l’art francais, vol. 7, 321–49. Paris: J.-B. Dumoulin, 1855–56.

- Pradère 1989a

- Pradère, Alexandre. French Furniture Makers: The Art of the Ébéniste from Louis XIV to the Revolution. Malibu, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1989.

- Ramond 2000a

- Ramond, Pierre. Masterpieces of Marquetry. Vol. 2, From the Régence to the Present Day. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2000. Originally published as Chefs-d’oeuvre des marqueteurs. Vol. 2, De la Régence à nos jours. Dourdan: Éditions H. Vial, 1996.

- Ramond 2000b

- Ramond, Pierre. Masterpieces of Marquetry. Vol. 3, Outstanding Marqueters. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2000. Originally published as Chefs-d’oeuvre des marqueteurs. Vol. 3, Marqueteurs d’exception. Dourdan: Éditions H. Vial, 1999.

- Salmon 2002

- Salmon, Xavier, ed. Madame de Pompadour et les arts. Exh. cat. Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2002.

- Secrest 2004

- Secrest, Meryle. Duveen: A Life in Art. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004.

- Stratmann-Döhler 2002

- Stratmann-Döhler, Rosemarie. Jean-François Oeben, 1721–1763. Paris: Éditions de l’Amateur and Perrin & Fils, 2002.

- The J. Paul Getty Collection 1972

- The J. Paul Getty Collection. Exh. cat. Minneapolis, MN: Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 1972.

- Watson 1981

- Watson, Francis John Bagott. “A Note on French Marquetry and Oriental Lacquer.” J. Paul Getty Museum Journal 9 (1981): 157–66.

- Wilson and Hess 2001

- Wilson, Gillian, and Catherine Hess. Summary Catalogue of European Decorative Arts in the J. Paul Getty Museum. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2001.

- Wilson et al. 2008

- Wilson, Gillian, Charissa Bremer-David, Jeffrey Weaver, Brian Considine, Arlen Heginbotham, Katrina Posner, and Julie P. Wolfe. French Furniture and Gilt Bronzes: Baroque and Régence; Catalogue of the J. Paul Getty Museum Collection. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2008.

- Wilson 1975

- Wilson, Gillian. “The J. Paul Getty Museum: 6ème partie: Les meubles baroques.” Connaissance des Arts 279 (May 1975): 107–13.