17. Two pairs of corner cupboards (encoignures)

- French (Paris), ca. 1750–60

- Carcass and mounts attributed to Jean-Pierre Latz (French, ca. 1691–1754, ébéniste privilégié du Roi before May 1741), marquetry panels attributed to Jean-François Oeben (French, born Germany, 1721–1763, ébéniste mécanicien du Roi from 1760 and master 1761), and 72.DA.69.1–.2 altered by Jean-Henri Riesener (1734–1806, master 1768 and ébéniste ordinaire du Roi from 1774)

- White oak* veneered with amaranth*, sycamore maple*, holly, fruitwood, barberry, boxwood, maple*, walnut*, and other unidentified woods; gilt bronze mounts; brass hinges; brass and iron locks and keys; brèche d’Alep tops

- H: 3 ft. 2 1/4 in., W: 2 ft. 9 3/4 in., D: 1 ft. 11 1/8 in. (97.2 × 85.7 × 58.7 cm)

- 72.DA.39.1–.2

- H: 3 ft. 1/4 in., W: 2 ft. 8 1/4 in., D: 2 ft. (92.1 × 81.9 × 61 cm)

- 72.DA.69.1–.2

Description

Although they differ slightly in dimension, these two pairs of double-door corner cupboards share a number of characteristics. The carcass of each of the four cupboards is fashioned from white oak, supplied with a brèche d’Alep marble top, and embellished with a profusion of gilt bronze mounts and floral marquetry. The doors are set with brass hinges, with the right door containing a single brass keyhole and iron lock. The front legs on the left and right sides of each cupboard take the form of short cabrioles, whereas a deep rounded apron forms the third, center leg. The interior of each cupboard reveals a single fitted shelf. Only the cupboards from pair 72.DA.39 contain posts that run vertically along the back of the interior. The white oak side panels of the cupboards come together at the back to form a 90° angle. The door panels are bowed in form, with those of 72.DA.69 presenting a slightly more bombé shape.

Both pairs of cupboards exhibit naturalistic marquetry on the exterior door panels. The marquetry consists of now-faded bouquets of carnations, daffodils, honeysuckle, narcissi, poppies, roses, tulips, jasmine, and other flowers. Each floral spray is unique and not bound by a ribbon or tie. They appear as if floating on the surface of the doors, although the overall composition and arrangement of flowers is looser on 72.DA.39 than on 72.DA.69. On the first pair (72.DA.39), the door panels feature a stained sycamore maple ground, bordered by amaranth along the edges and down the front two legs. Adopting the shape of a rounded rectangle, the stained sycamore maple section is further delineated by a foliate scroll frame of gilt bronze and contains the floral marquetry of amaranth, sycamore maple, holly, fruitwood, barberry, boxwood, maple, walnut, and other unidentified woods. The white oak interior of each cupboard is varnished. The second pair of cupboards (72.DA.69) is similarly veneered and set with gilt bronze mounts. The stained sycamore maple ground is framed by amaranth and contains the floral marquetry made from a similarly diverse assemblage of woods.

The gilt bronze mounts seen on both pairs of cupboards are remarkably similar. Each cupboard has a foliate scroll frame on each door, two sabots, two corner mounts, and a central apron mount. A flat gilt bronze frame follows along each cupboard’s lower front edge. The sabots consist of a mass of foliate scrolls that twist around a ridged middle section that is bisected by an undulating scroll. Each sabot is crowned with an outstretched wing. The corner mounts are similar in design, with foliate scrolls and a segmented, branchlike motif extending a third of the way down each cupboard’s sides and terminating in a leafy bud. The central apron mount features a pierced, shell-like rococo ornament set upon a series of matching asymmetrical foliate C-scrolls. The marquetry on each door front is surrounded by gilt bronze frames composed of foliate scrolls set with buds and leaves.

Marks

72.DA.39.1 features a printed paper label on the back, reading “Zollstück.” A paper label on the back of 72.DA.39.2 reads, “DEPT. OF WOODWORK ON LOAN FROM L Currie, Esq. No. 5/ 15.V.1917,” with the lender’s name handwritten in ink.

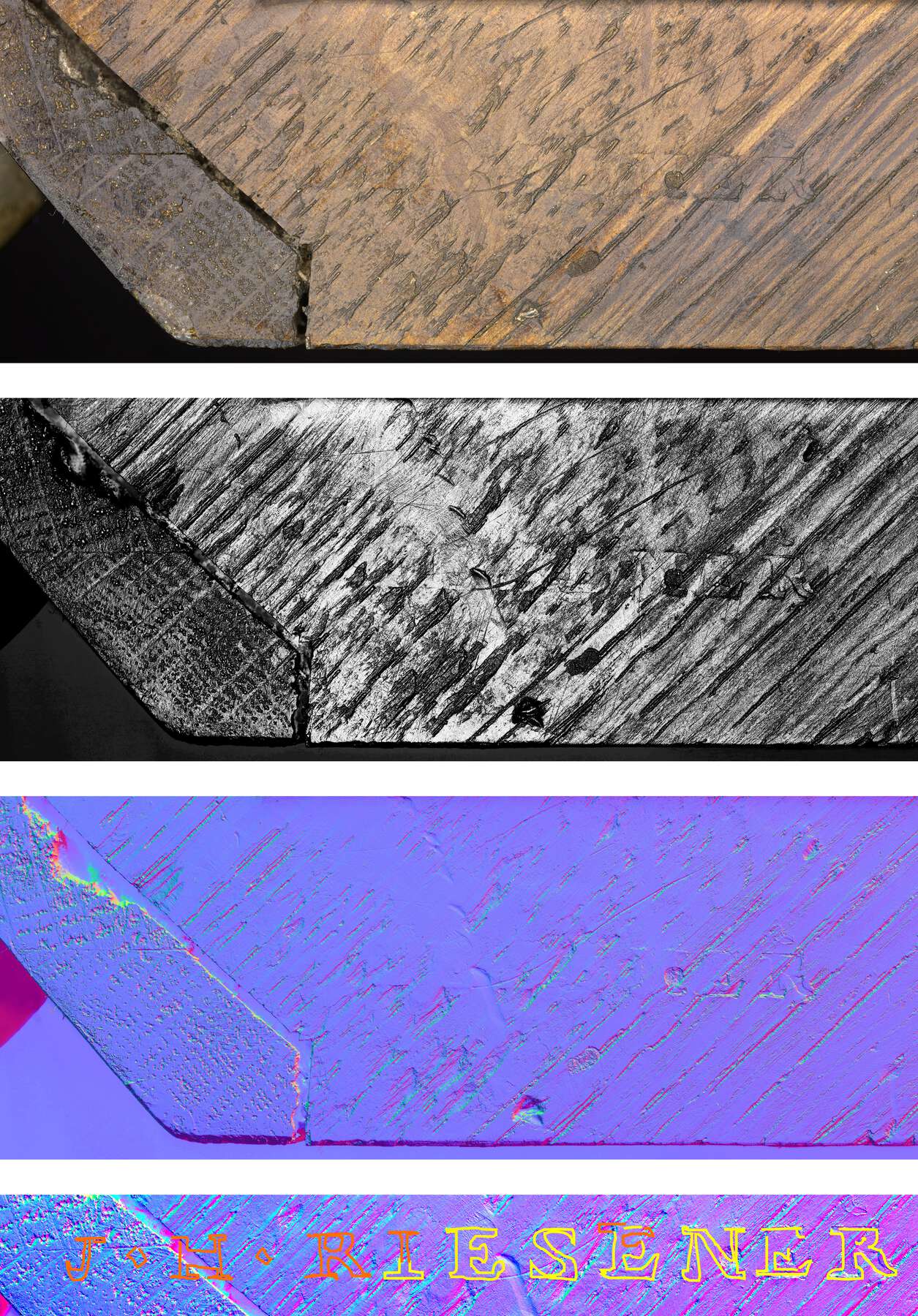

72.DA.69.2 features the stamp “J.H. Riesener,” for Jean-Henri Riesener, on the top right corner (see fig. 17-7, below). A handwritten inscription, presumably in pencil, on the cupboard’s underside reads, “Réparée le 13 Juillet 1843 / par [illegible] de Fère Champenoise / rue de Vitry No 29” (see fig. 17-8, below).

Commentary

These two pairs of corner cupboards and their gilt bronze mounts were attributed by Henry Hawley to Jean-Pierre Latz, born near Cologne around 1691 and naturalized in Paris in 1736.1 Referred to as encoignures, or coins, in the eighteenth century, such case pieces would have ordinarily been placed at the corners of a room, generally in single pairs.2 Latz, who did not always stamp his work and was named ébéniste privilégié du Roi in 1741, produced a number of such pieces. Among these is a pair of corner cupboards with stylized floral marquetry in the collection of the Palazzo del Quirinale that exhibit pierced rococo apron mounts very similar to those seen on the Museum’s cupboards (fig. 17-1).3 Made around 1750 and before Latz’s death in 1754, these unsigned cupboards are attributed to Latz on the basis of the similarity between their marquetry and that of a commode, also in the Quirinale (see fig. 16-3), that is in turn similar to another in the same collection but stamped by the maker and distinguished by its wave-cut bloodwood veneer.4 Both the Quirinale commode and the corner cupboards belonged to Louise-Elisabeth, Duchess of Parma, and were among the pieces that she brought to furnish the Palace of Colorno upon her arrival from Versailles in 1753.5 A pair of corner cupboards in the collection of the musée Carnavalet stamped by both Latz and Léonard Boudin offers a comparable overview of the former’s style as expressed in gilt bronze.6 Flanking the escutcheon of these cupboards’ upper drawers and seen along the corner mounts, the outstretched wing motif that alights from an exuberant scroll likewise graces the top of the Museum’s cupboards’ sabots.7

Figure 17-1

Figure 17-1Furniture made by and attributed to Latz embodies the stylistic repertoire of the Rococo. Although he is credited with the cupboards’ carcasses and mounts, the attenuated floral marquetry on their doors is believed to have been undertaken by Jean-François Oeben, another Parisian cabinetmaker of Germanic extraction, at a slightly later date.8 Any collaboration between these two cabinetmakers is based on circumstantial evidence, although there are several theories related to the possibility. Yannick Chastang made a connection between the Museum’s cupboards and an after-death 1756 inventory.9 Indeed, Oeben might have purchased furniture frames from Latz’s widow, Marie-Madeleine Seignat, who continued her husband’s business for two years before her death in 1756.10 The Museum’s cupboards are not the only pieces of furniture conjectured to have been begun by Latz and finished by Oeben. Commissioned by the Garde-meuble de la Couronne, a commode probably intended to furnish the bedchamber of the dauphine, Marie-Josèphe of Saxony, at the château of Choisy and now in a private collection, likely owes its carcass and mounts to Latz. Delivered in 1756 or 1757, the finished piece bears delicate floral marquetry on the sides and drawer fronts attributed to Oeben.11 In similar fashion, a small cabriole table in the collection of the Fine Art Museums of San Francisco, Legion of Honor, exhibits Latz’s stamp under the rail and Oeben’s under the drawer. This table’s overall form appears characteristic of an older craftsman at midcentury, whereas the marquetry is certainly in keeping with Oeben’s more natural aesthetics.12

Oeben helped usher in a new transitional style that combined rococo and neoclassical elements, a development notably seen in his commodes à la grecque made for clients that included the marquise de Pompadour and her brother, the marquis de Marigny, beginning around 1760.13 He is perhaps most famous for his involvement in the creation of the celebrated bureau du roi, a piece that he began in 1761 and was ultimately completed by his apprentice Jean-Henri Riesener and delivered to Versailles in 1769.14 For all his innovation, Oeben continued to produce more conventional rococo models and forms, among them two stamped multipurpose cabriole tables (cat. nos. 18, 19) also in the Museum’s collection.

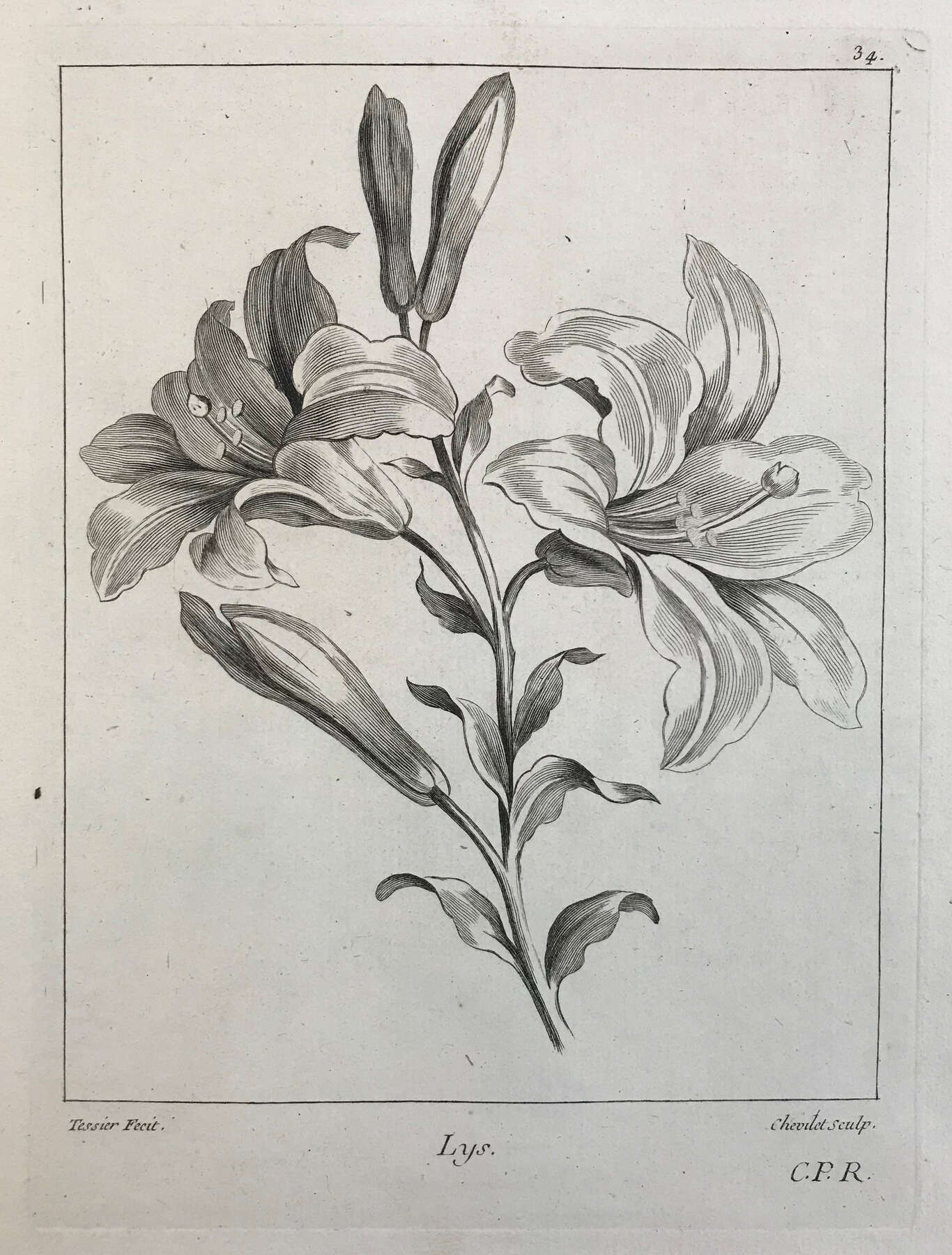

A hallmark of Oeben’s style is the use of elegant, realistic floral marquetry. For his design, it appears that he found his inspiration in Louis Tessier’s Livre de principes de fleurs, dédié aux dames, with engravings by Juste Chevillet.15 A securely dated example demonstrating Oeben’s Tessier-inspired marquetry is the above-mentioned bureau du roi with elements directly derived from plates 43 and 44 (Jasmin d’Espagne) of the book. Conceived as a ladies’ guide to drafting and shading techniques, this book actually proved to be an indispensable resource for cabinetmakers. It showcases models for various floral specimens by Louis Tessier (1719–1781), an artist who spent his entire career, if not his life, working at the Gobelins Manufactory.16 While a manuscript copy of the book contains a frontispiece dated 1755, the printed versions of the Livre are undated but generally thought to date from the same year or soon after.17

The publication of the Livre after Latz’s death effectively precluded him from ever having produced such marquetry for the Museum’s corner cupboards. Chastang has identified several plates from Tessier’s book and other publications by him as the basis for marquetry designs by cabinetmakers like Oeben.18 For example, at least four of Chevillet’s engravings in the Livre were reproduced to create the now-faded marquetry flowers seen on 72.DA.69. These include plates 29 and 30 (Semi-double simple [géroflé]), 31 and 32 (Rose double), 33 and 34 (Lys) (see fig. 17-2), and 43 and 44 (Jasmin d’Espagne). The other flowers are from an as yet unidentified source, and it is worth noting that in instances where the same species is repeated in the marquetry, they are not all conclusively sourced from Tessier. Oeben kept a ready and apparently large supply of precut flower motifs at hand, as seen in the following entry from the 1763 inventory of his workshop.

Un petit coffre-fort remply de fleurs en bois découpé et nué, propres à être employés en différens ouvrages, dont la plus large est d’environ 3 ou 4 pouces et la plus petite de la largeur de 3 lignes, lesquels il a été impossible de compter et décrire, attendu la quantité considérable qui s’en trouve et la différence des espèces, prisé le tout ensemble (non compris led. petit coffre fort qui a été prisé cy devant dans les effets du magasin d’où il a été tiré pour servir à renfermer lesd. fleurs) la somme de 400 livr.19

Figure 17-2

Figure 17-2Other Oeben pieces feature similar marquetry flowers. For example, a pair of corner cupboards by Oeben in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum repeat the tulip and carnations seen on the right door of 72.DA.39.1.20 The frieze of a circa 1760 writing table at the Rijksmuseum features the same cut rosebud seen on the left door of 72.DA.69.1.21 The question of who was actually responsible for producing the flowers themselves remains, however. Oeben’s status as ébéniste mécanicien du Roi from 1760 on freed him from guild restrictions, and he took advantage of this privilege to create everything from metal frames and mounts to more functional hardware, including locks.22 Although the creation of elaborate marquetry figures was also part of his business, it is entirely possible that some of this was contracted out by a marqueteur working for Oeben or even Latz’s widow. She might have sought such assistance, and her own operation of Latz’s business coincided with the earliest possible publication date of the Livre de principes de fleurs.

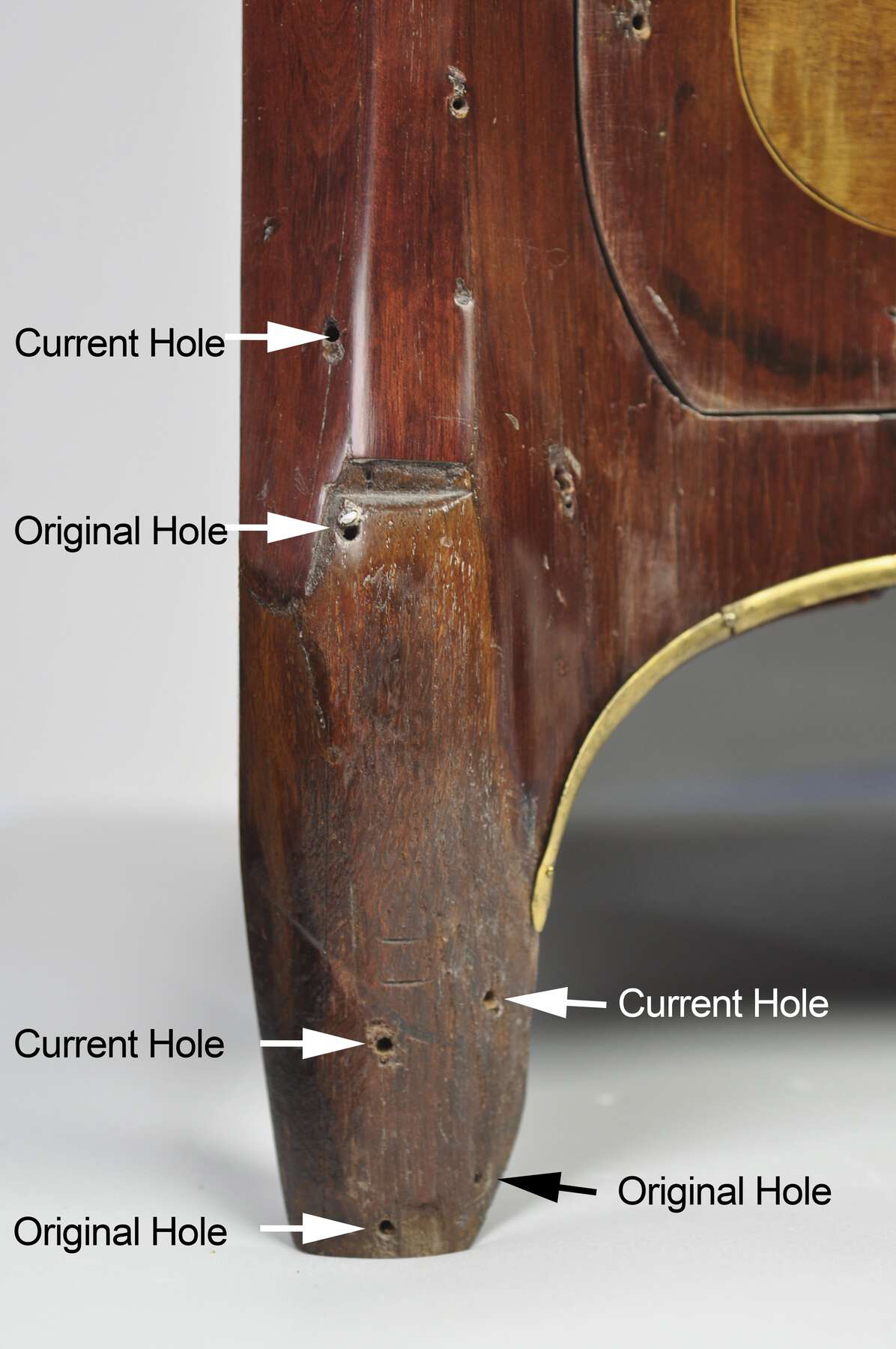

Of further interest with respect to the trajectory of furniture from one maker to another, the right-hand top corner of cupboard 72.DA.69.2 reveals the now-faint stamp of Jean-Henri Riesener (see fig. 17-7, below). Technical analysis indicates that this pair of cupboards was shortened at both the top and the bottom sometime after production. The presence of Riesener’s stamp on the one cupboard suggests that these changes took place sometime after he took over Oeben’s workshop in the mid-1760s. Indeed, Riesener was only entitled to begin stamping his own work as a master in 1768.23 However, the handwritten cursive inscription on the bottom of 72.DA.69.1 references a repair made in July 1843 by someone working at 29, rue de Vitry in the commune of Fère-Champenoise, in the Marne Department. Although the Museum’s pair might have been shortened at this date, the presence of Riesener’s stamp on top of the one cupboard suggests that the alterations, perhaps part of a restoration or refurbishment, were made in Riesener’s workshop in the Arsenal, which remained in operation until 1798.

Provenance 72.DA.39.1–.2

By 1917–after 1920: Lawrence Currie, English, 1867–1934 (London, England);24 –1936: private collection (Berlin, Germany) [sold, Kunstbesitz eines Berliner Sammlers, Hugo Helbing Gallery, Frankfurt am Main, June 23, 1936, lots 260–61]; –1938: private collection (Germany) [sold, Eine Bekannte Süddeutsche Privatsammlung und Anderer Privatbesitz, Kunsthaus Lempertz, Cologne, March 12, 1938, lot 217]; –1955: private collection (New York, NY) [sold, Fine French XVIII-Century Furniture & Decorations, Parke-Bernet Galleries, New York, October 21–22, 1955, lot 358, to Dalva Brothers, Inc.]; 1955– : Dalva Brothers, Inc. (New York, NY), sold to Philip Robert Consolo;25 Philip Robert Consolo, American, 1915–2011 (Miami, FL);26 possibly private collection (California);27 –1972: Frank Partridge & Sons, Ltd. (London, England), sold through French and Company to the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1972.28

Provenance 72.DA.69.1–.2

Sidney J. Block (London, England);29 –1972: French and Company, Inc. (New York, NY), sold to the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1972.

Exhibition History 72.DA.39.1–.2

Loan to Victoria and Albert Museum, Victoria and Albert Museum (London), May 9, 1917–May 26, 1920.

Exhibition History 72.DA.69.1–.2

Loan to the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute (Williamstown, MA), May 20, 1998–February 27, 2009.

Exhibition History 72.DA.39.1–.2 and 72.DA.69.1–.2

The J. Paul Getty Collection of French Decorative Arts, Detroit Institute of Arts (Detroit), October 3, 1972–August 31, 1973; Paris: Life & Luxury, J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Center (Los Angeles), April 26, 2011–August 7, 2011; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (Houston), September 18, 2011–January 2, 2012.

Bibliography 72.DA.39.1–.2

, 254, no. 49, ill.; , 32, no. 36; , 133, 135, ill.; , 21, no. 36; , 50, ill.; , 120–22; , 104–5, fig. 62; 166, no. 4.

Bibliography 72.DA.69.1–.2

, 255, no. 50, ill.; , 32–33, no. 37; , 133–34, ill.; , 21, no. 37; , 120–22; , 116, no. 5.

- P.H.

Technical Description

The structure of the two pairs of cabinets is currently rather different, however the physical evidence suggests that their original construction was quite similar. It appears that both pairs have been modified in different ways since the time of their fabrication. In this essay, the original construction of both pairs is described, followed by a discussion of the ways in which each has been modified.

The original fabrication of both pairs of cabinets was based on a plank construction using variants of tongue-and-groove joints. The two back planks of each cabinet were made of five or six boards of white oak about 1.8 cm thick, butt joined and glued together on edge (fig. 17-3). The panels were joined together at the rear corner using a rabbet-and-groove joint along their entire length. At the front corners, pseudo-posts were formed by laminating long pieces of wood, approximately 5 x 9 cm in section, to the interior surfaces of the planks along their front edges. These composite posts were then sawn and shaped to their final form. Sections along the lower edges of the rear planks were cut away to form the front and rear feet; a small, chamfered glue block about 3.2 mm square was glued into the back corner, below the case bottom, to reinforce the rear foot and support the case bottom.

Figure 17-3

Figure 17-3The triangular bottoms of the cabinets were also made from single large planks. Each bottom was formed of six boards butt joined and glued together on their edges, with the grain of the wood running parallel to a line drawn between the corner posts. The bottom planks, about 20 mm thick, were slightly rabbeted on the lower side of their back edges and were fitted into long horizontal dadoes running the width of the back planks. Along their front edges, the bottom planks ran all the way to the front of the cabinets, flush with the door fronts above. Below the front edge of the case bottoms, curved blocks of wood approximately 4.5 cm high and 4 cm deep were glued in place, forming an auxiliary rail running from corner to corner on each cabinet. Each of these rails was made of two pieces of wood, joined at the center with a slip joint. At either end, the rails were attached to the corner posts with a variant of a slip joint using a loose tenon. Three additional blocks of wood were stacked and glued to the bottom of each rail at the center to form the apron.

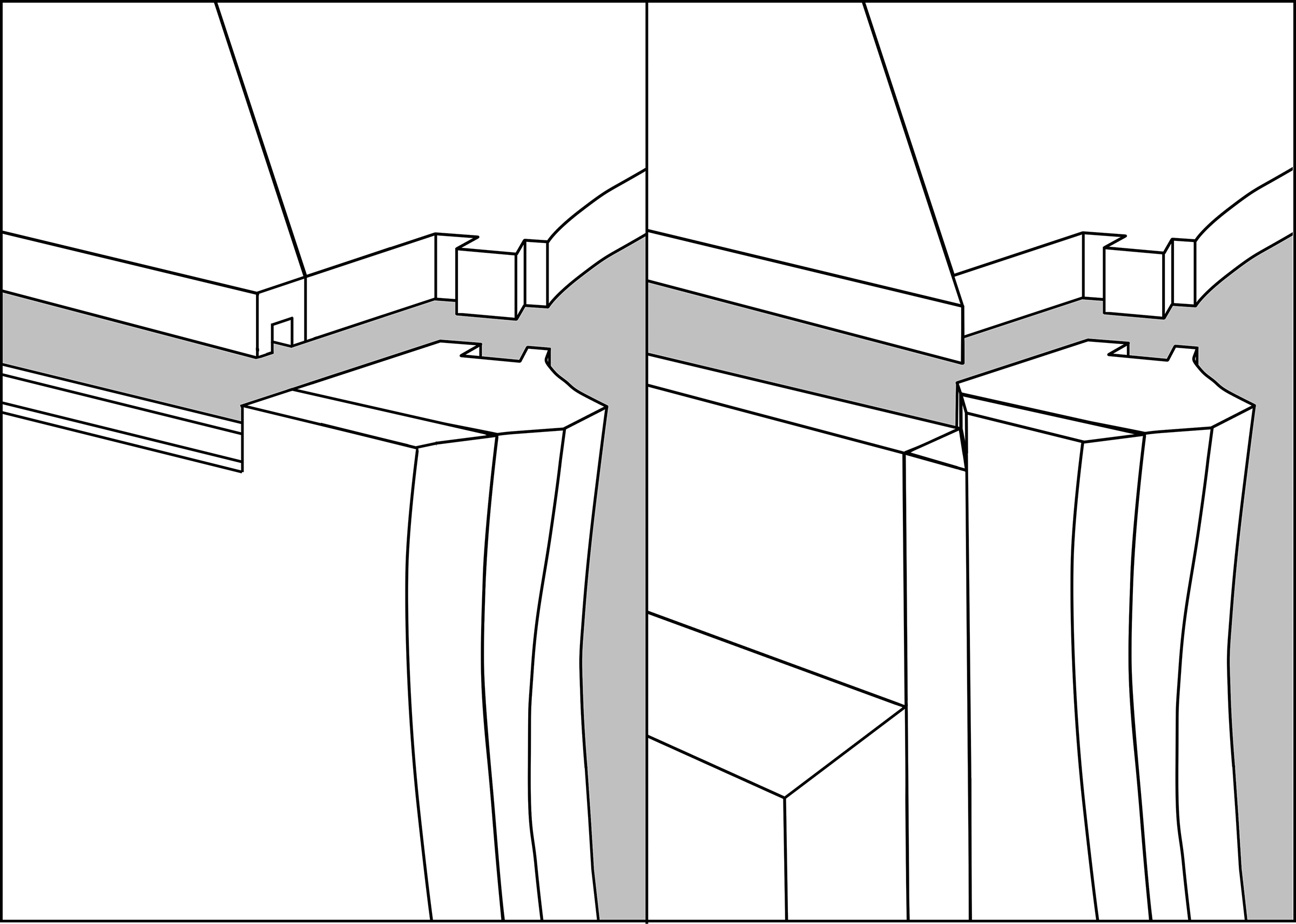

Due to subsequent modifications made to both pairs of cabinets, the original construction of the case tops is not understood in complete detail. However, in keeping with the rest of the original construction, the tops were almost certainly constructed of solid planks, and both pairs of cabinets are currently fitted with such tops. How the tops were originally joined to the case backs is a matter of speculation since both pairs have been modified in this area. Along the front edges, it appears that cabinets 72.DA.39.1–.2 retain their original joinery. These case tops were extended to the very front edge of the cabinets and joined at their ends to the front posts with small dovetails (fig. 17-4). Below the front edges, curved strips of oak were glued to their undersides to form an auxiliary rail in a manner analogous to the blocks added below the case bottom; that is, they are joined at the middle with a slip joint and attached to the corner posts with loose tenons.

Figure 17-4

Figure 17-4The doors of the cabinets were made in a laminated construction with cross battens at top and bottom. On pair 72.DA.69.1–.2, the laminated vertical sticks of oak are approximately 2.5 cm in width; on pair 72.DA.39.1–.2 they are approximately 4.5 cm wide. The cross battens, attached at top and bottom with tongue-and-groove joints, were also laminated using sticks of corresponding dimension. In addition to the difference in stick size, there are significant differences between the two pairs of doors, both in size and in shape. The doors of 72.DA.69.1–.2 are approximately 2.5 cm taller than those of 72.DA.39.1–.2, and they have a more pronounced bombé form than their counterparts. Although the cases of 72.DA.69.1–.2 have been shortened (see below), it appears that the cabinets overall were originally taller than those of 72.DA.39.1–.2 by a corresponding amount. While virtually every other detail of construction was identical between the pairs, these differences suggest that they were not made as a set of four at the same time.

As mentioned above, both pairs of cabinets have been altered since their construction. In particular, the pair 72.DA.69.1–.2 has been shortened by approximately 7.5 cm, removing approximately equal amounts of material from both the top and bottom. This is evident when the corner mounts and apron mounts are removed. Old screw holes are readily apparent (either by eye or by X-radiography in areas where veneer replacements cover the old holes). These holes clearly indicate the exact position of the mounts before the shortening occurred (figs. 17-5, 17-6). The amount of shortening can be determined by measuring the offset of the new and old holes. At the bottom, the shortening appears to have been accomplished by cutting about 3.7 cm off the ends of the three legs. The apron was also cut down, roughly following the contours of the newly positioned apron mount.

Figure 17-5

Figure 17-5 Figure 17-6

Figure 17-6At the top, cutting down the cabinet was somewhat more involved. Along the front edge, it appears that the front posts and the composite front rail were cut down by approximately 3.7 cm. The top panel (which ran to the front edge of the rail) must then have been completely cut away. It appears that the original top panel was then remade, possibly using some of the original wood but without dovetails attaching it to the corner posts. This may have been necessary because when the corner posts were cut down, the mortise and tenons of the front rail joinery were exposed at the tops of the posts; cutting a dovetail mortise into this exposed joinery may have been considered unwise. Rather than dovetails, the remade top was set into a large rabbet in the top of the posts, completely covering the underlying joinery. This required the remade top to be larger than the original top, so at least this section must have been fabricated using a new piece of wood. Between the posts, the top was set into a rabbet cut into the rear edge of the front rail. The back panels of the cabinets were then cut down by an additional 1.5 cm (beyond the amount removed from the posts and rails) to allow for the top to sit on top of them; they are secured to the top with a rabbet-and-dado joint along their entire length.

The top on cabinet 72.DA.69.2 is marked at its right corner with a recently discovered stamp of J. H. Riesener (fig. 17-7). Reflectance transformation imaging (RTI) was used to help visualize the faint remnants of the stamped impression.30 This process involves taking approximately thirty images under a range of lighting conditions from which a composite is made using several different RTI modes.

Figure 17-7

Figure 17-7The stamp was struck on the replaced section of the top that seems to have been added during the shortening of the cabinets. This suggests the possibility that Riesener (who took over the direction of Oeben’s workshop sometime between 1763 and 1765) carried out the shortening. Riesener is certainly known to have executed such structural modifications, as exemplified by a commode in the Frick Collections (15.5.76) that was made by Riesener himself in the mid-1780s and then extensively modified, including shortening and remounting, in 1790–91. If this were the case, the shortening would have been executed after Riesener became a master (entitled to stamp his own work) in 1768. Whether Riesener shortened the cabinets or not, the presence of his stamp suggests that the work was done before about 1798, the last year he is known to have had an active workshop at the Arsenal in Paris.31

In addition to the Riesener stamp, there is an inscription, apparently in pencil, on the bottom of the same cabinet (fig. 17-8). In a bold cursive hand is written “Réparée le 13 Juillet 1843 / par [indecipherable] de Fère Champenoise / rue de Vitry No 29.” Fère-Champenoise is located approximately 100 km east of Paris in the Ardennes. It cannot be entirely ruled out that the shortening of this pair of cabinets was executed at this time, though the Riesener stamp on the apparently remade top suggests that this is unlikely.

Figure 17-8

Figure 17-8The cabinets 72.DA.39.1–.2 have not been shortened, and they essentially retain their original aspect from the front. Behind their facade, however, this pair has also been dramatically altered. It appears that the entire cases, behind the front posts, have been replaced with new construction. The construction of the front section of this pair of cabinets is very similar to that of 72.DA.69.1–.2, with the minor differences outlined above. It appears that the sections of the top and bottom panels that run between the corner posts and forward to the front of the case are original. Behind the plane defined by the corner posts, however, the boards of both panels are thinner by 2 to 3 mm and appear to be replacements. The current construction of the case backs is based on a frame-and-panel construction; however, the evidence suggests that they were originally of plank construction like those on 72.DA.69.1–.2.

Viewed from above, it is evident that the corner posts are composite elements with a strip of oak, running the full height of the case, glued to the outside face of the main timber. Practically, there is no advantage to (or need for) this configuration, as the posts are not of large cross-sectional dimension. The explanation appears to be that the added strips are the remnants of the original case back panels that were subsequently cut off behind the posts. The intact joinery between back plank and corner post can still be seen on the 72.DA.39.1–.2 cabinets, with its glue line in precisely the same location on both. The remnant strips of the back panels have been thinned somewhat, and as a result, the overall dimension of the corner posts is slightly smaller than the posts of the 72.DA.69.1-.2 cabinets, which have not been thinned. When the rear sections of the cabinets were removed, the restorer apparently made a continuous and expedient cut through the top and bottom panels as well as through the rear edges of the corner posts. As a result, the latter were left with an awkward, chamfered face at the rear. In order to return the posts to square, the restorer was then obliged to glue on a triangular strip of wood to these chamfered faces before proceeding to construct his new frame-and-panel structure (see fig. 17-4).

A detailed examination of the rear, frame-and-panel, construction of this pair of cabinets gives some clues as to their origin. In particular, the replaced sections of the case bottoms (behind the corner posts) are attached to the bottom edge of the lower rails with modern wire finishing nails only. No other joinery secures the case bottom, and there is no evidence that the nails have ever been replaced; these nails thus appear to be an integral part of the reconstruction of the cases (fig. 17-9). As wire finishing nails were only in common use after about 1880, it would appear that the rebuilt cases were made subsequent to this date. Further refining the date, the presence of the dated Victoria and Albert Museum label on the rebuilt back of cabinet 72.DA.39.2 (see “Commentary” above) demonstrates that the alteration predates 1917.

Figure 17-9

Figure 17-9Given that the cabinets were in England by 1917, it seems plausible that the rebuilding of the cases occurred in England as well. The fact that the rear posts are exactly 2 in. square in cross section, many of the horizontal rails of the back panels are exactly 2 in. wide, and the wire nails are 1 1/4 in. long supports this supposition.

Both pairs of cabinets have had some replacements to the original lock and catch hardware. On cabinets 72.DA.69, the locks (installed in the right-hand doors) have clearly been replaced, as evidenced by two complete sets of screw holes in the lock mortises. These cabinets, however, retain the original catch mechanisms for the left-hand doors. These are composed of flexible iron straps attached to the underside of the shelves, whose ends slip over and catch on small decorative iron hooks that are screwed into the rear side of the left doors. Cabinets 72.DA.39.1–.2 retain their original iron locks and elegant dolphin keys (fig. 17-10); however, the left door catch mechanisms have been removed and replaced with English-style recessed catches installed at the top inner edge of the doors.

Figure 17-10

Figure 17-10The majority of the gilt bronze mounts were removed from all four cabinets for examination and analysis. The mounts on 72.DA.39.1–.2 are noticeably more corroded than those from the other pair, both on the fronts and on the backs, possibly as the result of exposure to atmospheric pollutants that were particularly intense in the area around London in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It would appear that the mounts for all four corner cabinets were prepared and fitted to the carcasses as a group. Each set of corresponding corner mounts (from the tops and bottoms of the leg posts) are numbered from 1 to 4 with filed notches. The mounts from cabinets 72.DA.39 are marked 1 and 2, while those from 72.DA.69 are marked 3 and 4. On both sets of corner mounts, one of the four was clearly the model from which the other three were cast. This is evident from unique chisel marks or casting repairs that have been duplicated through casting into the other three copies (figs. 17-11, 17-12). In both cases, the original mount is currently placed on one of the 72.DA.39 cabinets.

Figure 17-11

Figure 17-11 Figure 17-12

Figure 17-12The framing mounts on the doors tell a slightly different story; here again, most of the corresponding pairs of mounts on the 72.DA.69 cabinets are marked with three and four file marks, respectively. In some cases the corresponding mounts from 72.DA.39 are marked as 1 and 2; however, in at least two cases the mounts on these cabinets are clearly copies of one of the 72.DA.69 mounts and the three or four file marks on the latter are reproduced on the former. As mentioned above, the doors of the 72.DA.69 pair of cabinets are slightly taller than those on the 72.DA.39 cabinets. It would appear that the framing mounts were originally made to fit the larger door size. As a result, many of the 72.DA.39 framing mounts have been shortened when they were fitted to their doors. This was accomplished by cutting out small sections of the mounts (in areas with little ornamentation) and then soldering the mount back together (fig. 17-13).

Figure 17-13

Figure 17-13X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis to determine alloy composition was conducted on 22 mounts from 72.DA.39.1–.2 and on 30 mounts from 72.DA.69.1–.2. In addition, two samples of soldering metal (sections of mounts) from each pair of cabinets were analyzed, along with one area of amalgam gilding from each pair. The mounts all appear to have typical compositions for mid-eighteenth-century castings, with 18–25% zinc, about 1% tin, and 1.5% lead, along with distinct traces of impurities such as antimony, iron, silver, nickel, and arsenic. There is no clear clustering of compositions that would suggest that any particular group of mounts from one or the other pair of cabinets was cast separately from the others. The solder used on both pairs of cabinets appears consistent and has zinc contents measuring 30–33%. Analysis of the gilded surfaces shows a considerable thickness of gold and the definite presence of mercury, both consistent with traditional amalgam gilding.

The corner cabinets are decorated with floral marquetry panels framed with amaranth. Sampling of the marquetry woods for anatomical analysis was not possible, so close examination of the macroscopic features was employed to identify the many different woods used on the marquetry. The flowers, inlaid in a stained sycamore maple background, were identified as being of holly, sycamore maple, fruitwood (possibly pear or apple wood), barberry, boxwood, and an unidentified tropical wood (used only on the left door of 72.DA.69.1). Many of the flowers are made from a single piece of veneer, and the contrast in tone still visible today is the result of careful sand shading and the use of carefully selected wood grain. The stems of the rosebushes are made from kingwood to imitate mature stems. This careful selection of marquetry wood is symptomatic of the furniture produced in the workshop of Jean-François Oeben. The black leaves and stems in the marquetry, previously thought to be ebony, are actually holly that was originally dyed green but that has degraded to near-black over time (see “Technical Description,” cat. no. 18).

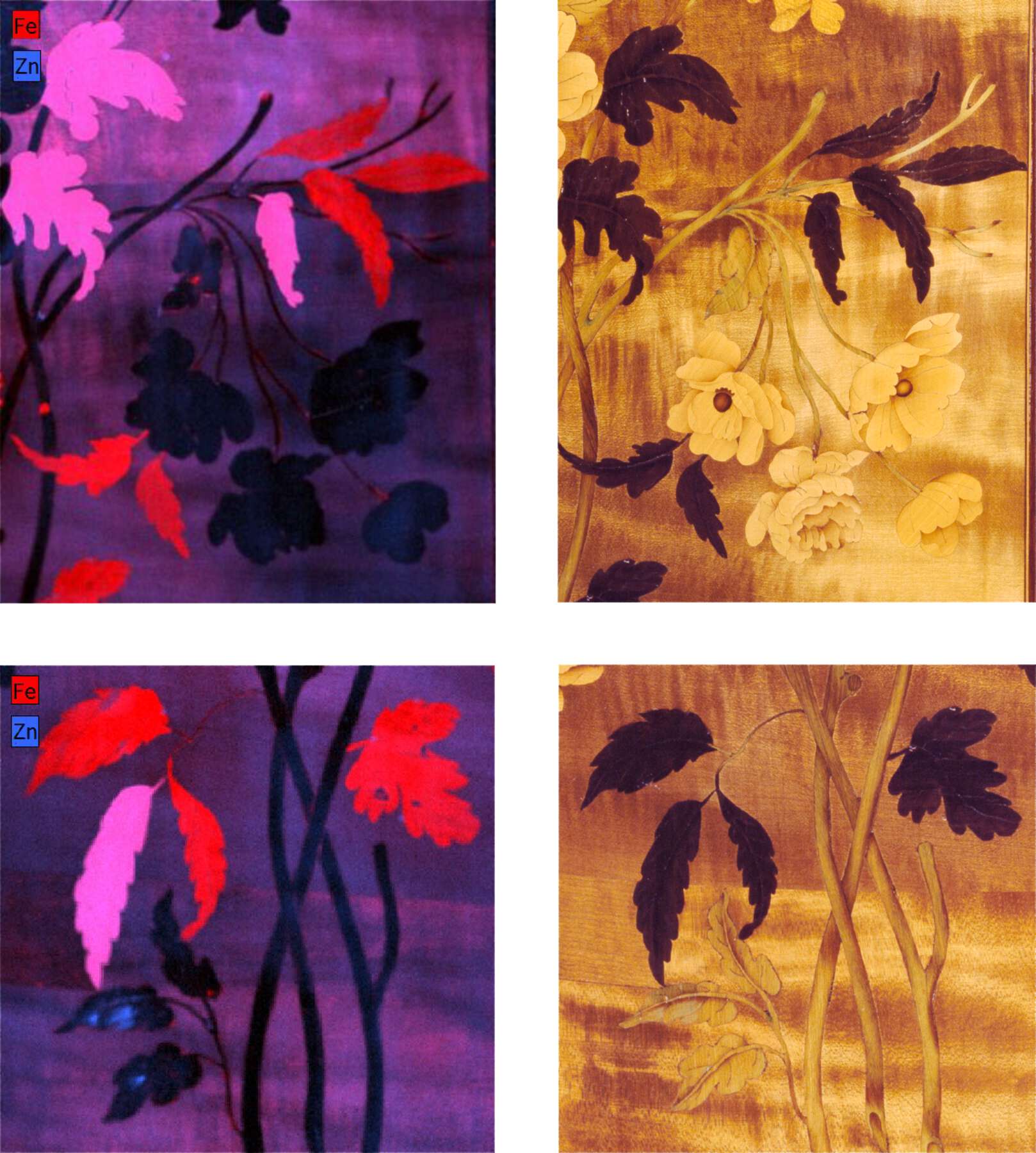

The original green dye recipe used by Oeben for these leaves and stems appears to have used the yellow dye young fustic (derived from the wood of Cotinus coggygria) in combination with an iron sulfate mordant. Iron sulfate, vitriol vert or couperose at the time in French, was a product of copper mines and was available in Paris from several sources in the eighteenth century.32 Hickel has shown that iron sulfate from European copper mines could be highly impure, often containing complex mixtures of sulfates of iron, zinc, manganese, aluminum, potassium, magnesium, and copper.33 Initial spot XRF analysis of the blackened leaves in the marquetry of these cabinets quickly revealed that iron sulfate from at least two different sources was used to create the original green color. Some elements showed a dominant signal for iron alone, while other elements clearly contained large concentrations of both iron and zinc. Subsequent XRF macroscanning of sections of a door from cupboard 72.DA.69.2 (fig. 17-14) shows how leaves with high iron content (appearing red in the scans) appear mixed in the composition with leaves that contain both iron and zinc in high concentration (shown as fuchsia).

Figure 17-14

Figure 17-14Informal experiments to reproduce Oeben’s green-dyed holly in the conservation laboratory of the Museum used different blends of impure iron sulfate per Hickel’s formulations. The results suggest that different shades of green are created depending on the composition of the iron sulfate, with more impure mixtures producing lighter, brighter greens and purer iron sulfate yielding significantly darker tones. It appears likely, then, that Oeben used different qualities of iron sulfate to produce batches of different shades of green-dyed wood. He then selected leaves dyed from different batches of veneer to create a sophisticated palette of tones in his final compositions.

The highly figured sycamore maple background, which is now a slightly greenish-brown (this color is often referred to as tobacco green), was almost certainly originally a silvery gray, referred to in the eighteenth century as “satiné gris.” This sycamore maple veneer, with its dramatic rippled patterning, would have had an appearance similar to a fashionable gray moiré silk, called “tabis.” XRF analysis of the veneer shows elevated levels of iron and zinc in the sycamore maple background (though substantially less than found in the blackened leaves mentioned above). The same iron sulfate used for the green leaves discussed above is also the primary ingredient mentioned by Roubo for dying wood gray,34 and experiments in the Museum’s conservation laboratory confirm that a bright, silvery gray tone can be easily imparted to sycamore maple using dilute solutions of iron sulfate. It is not uncommon to find eighteenth-century documents describing furniture with marquetry in satiné gris. Where these pieces can be identified today, they also have highly figured sycamore maple veneer, now turned toward greenish-brown.35

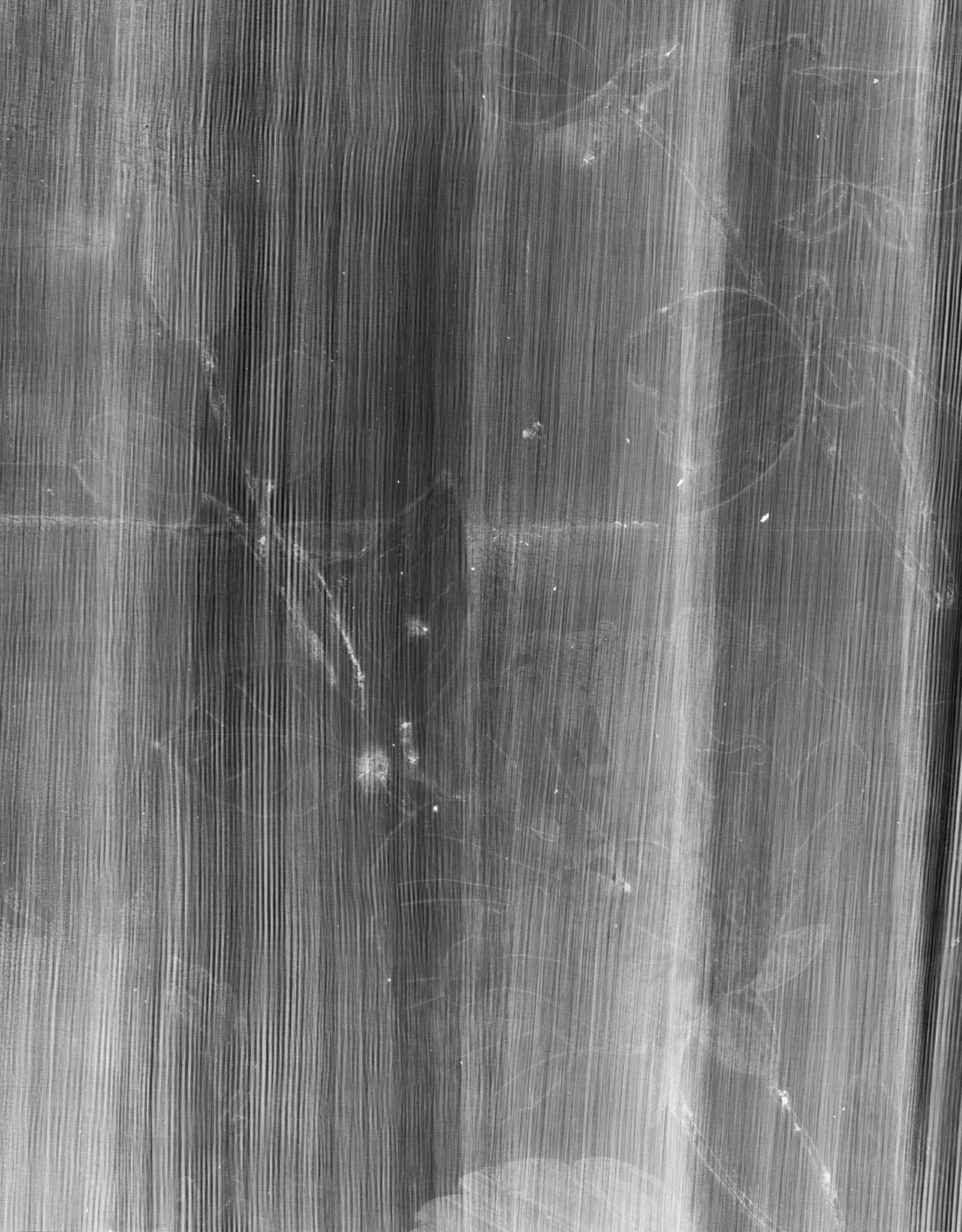

Based on evidence revealed by examination of the marquetry decoration, X-radiography, and tool marks present on the corner cabinets, it is likely that the majority of the marquetry was cut using a fretsaw with the stems and leaves inlaid using an inlay knife. The flowers, leaves, and stems were partly cut as individual pieces and partly stack cut using a piercing saw that produced a saw kerf (the gap left by the width of the saw) of about 0.2 mm on the flowers. Some flower elements were shaded by leaving individual pieces of veneer to heat in hot sand until the desired level of singeing was obtained. The elements forming a flower were then drawn together into the flower shape to eliminate the saw kerfs left by the saw blade. Once assembled, the flowers were glued to a piece of paper and then inlaid in the sycamore maple background using the fretsaw. The advantage of this technique was that ready-made, possibly even subcontracted flowers could be created in advance and made ready to be inlaid and glued on a finished carcass. The rounded shape of the flowers and the extremely high quality of their fitting into the sycamore maple background suggests that they were saw cut using a technique known as bevel cutting or conic cutting (see also cat. no. 19). The process is similar to boulle marquetry or stack cutting, where two veneers are cut simultaneously; however, unlike boulle marquetry cutting, the saw blade is angled slightly and the kerf created by the saw blade disappears when the top piece is dropped into the hole created in the lower veneer. This technique results in flawless joins, although only a single marquetry composition can be made at a time. The small stems and leaves that connect the separate flowers were subsequently inserted using a shoulder knife, and a few knife marks can be seen in these areas (fig. 17-15).

Figure 17-15

Figure 17-15X-radiography also helps to confirm the use of two separate techniques. In X-ray, the outlines of the flowers are relatively faint, while the stems are more pronounced, probably due to a thicker layer of glue present in the grooves made by the knife cuts (fig. 17-16). This confident mixing of techniques is typical of an accomplished marquetry workshop. Conic cutting had apparently only recently been developed at the time of the manufacture of these corner ccabinets. The relatively small size of the marquetry designs produced by bevel marquetry is symptomatic of eighteenth-century technical limitations.

Figure 17-16

Figure 17-16There is some occurrence in the marquetry of engraved lines filled with black pigment. Engraving additional lines to add detail to a composition was common in Oeben’s work, but repeated scraping, a common restoration practice from the eighteenth century to the present day, must have resulted in the loss of engraving decoration. Although some engraving remains, one can only speculate on how much more has been lost. The occurrence of lines drawn in ink on the marquetry is almost certainly the result of later restorers replacing lost engraving lines (fig. 17-17).

Figure 17-17

Figure 17-17The condition of the marquetry is generally good, although in some areas there has clearly been considerable scraping of the surface during previous restorations. In some instances, such as on the left door of the corner cabinet 72.DA.39.1, the scraping appears to have been done in conjunction with the repair of splits in the substrate oak. On this door, the long split has caused visible damage to the veneer; however, in the middle of the split, one flower appears entirely undamaged. This flower also exhibits significantly stronger sand shading than the surrounding marquetry. These two characteristics suggest strongly that the flower has been replaced (fig. 17-18). On the lower portion of the right door on the same cabinet, a section of the sycamore maple background veneer has been scraped sufficiently to remove the gray-stained surface layer, exposing the light tone of the natural wood.

Figure 17-18

Figure 17-18There have been some significant replacements to the amaranth veneer on the cases of the cabinets. In particular, the majority of the veneer on the aprons (below the doors) has been replaced on both 72.DA.39 cabinets along with several smaller sections along the top rail. It would appear that both aprons have had serious horizontal breakages in the past that probably badly damaged the original veneer, leading to its replacement. The glossy varnish is continuous across all areas of restoration, implying a fairly recent application, possibly shortly before the cupboards’ acquisition by the Museum.

X-radiographic examination revealed several small square holes that mark the location of veneer pins used during assembly of the marquetry. Traditionally, veneer pins were used to stop pieces of veneer from sliding out of position during gluing and clamping; they were hammered into the substrate wood next to the edge of the veneer and removed once the glue had dried. Subsequent pieces of veneer would then cover over these holes so that today they are only visible by X-radiography. It is clear from the location of the veneer pin holes that the amaranth frame was glued in position first, followed by the black and white border strips and finally by the central marquetry.

The four marble tops are made from brèche d’Alep from the Bouches-du-Rhône, France. It is a yellow, pink, red, and black breccia marble with round and some angular clasts, with a reddish-orange cement made of sediment grains similar to the larger fragments. The clasts are fine-grained in nature, and occasional fossils of bivalves can be seen. This indicates an aquatic environment for the source of the clasts. There are some fractures infilled by reddish-orange cement that cross-cut the large grains and must have preceded the formation of the stone, yet the fracture happened before cementation had occurred.

- A.H.,

- Y.C.

- and R.S.

Notes

The standard monograph is , 203–59; the Museum’s cupboards are reproduced as nos. 49 and 50, 254–55. See also , 176–82; , 482–89; , 152–61. Hawley attributes these cupboards to Latz but tempers his conclusion by noting that mounts of similar design are not found on any other pieces stamped or firmly attributed to him. He dated them to about 1750. ↩︎

, 160–61. ↩︎

A related apron mount can be seen on a pair of corner cupboards attributed to Latz in the collection of Schloss Wilhelmstal, inv. no. Z 92/1, near Cassel in northern Hesse. This pair is cited in , 253–54, no. 48. ↩︎

See . The stamped Quirinale commode, which is similar to the Museum’s attributed to Latz (cat. no. 16), is reproduced on pp. 231–32, no. 21; the nonstamped, marquetry commode is reproduced on pp. 237 and 239, no. 28; the corner cupboards are reproduced on p. 253, no. 47. ↩︎

See , 48–59. ↩︎

Boudin, who was born in in 1735, could not have applied his own stamp before 1761, when he was named a master cabinetmaker. Hawley suggests that Boudin, who specialized as a marqueteur and eventually operated as a marchand-mercier, might have acquired the Carnavalet cabinets, finished or not, with the mounts and repaired, altered, or finished them himself. Possibly a later addition by Boudin or another marqueteur, the marquetry is markedly naturalistic. See , 324, no. 24. See also , 484; , 88–91, cat. no. 28. ↩︎

The outstretched wing mount is also seen on a pair of corner cupboards in a private collection signed by Latz and presumably stamped with the mark of the château d’Eu, reproduced in , 232–33, no. 22. ↩︎

The most recent and comprehensive monograph of Oeben and his work is . The author does not cite the Museum’s cupboards in the appendix of Oeben’s signed or attributed furniture but discusses 72.DA.39 and illustrates 72.DA.39.2 on pp. 50–51, respectively. See also , 252–63; , 58–69. ↩︎

, 122 n. 24, refers to items 32 and 40 in Seignat’s 1756 inventory that quite possibly refer to the Museum’s cupboards, then in an unfinished state. See Paris, Archives nationales de France, Minutier central, XXVIII, 348, December 20, 1756: “32. Item une paire de bâtis d’encognures de bois de chêne dont les fermetures sont de cuivre prisé ensemble douze livres”; “40. Item deux bâtis d’encognures de bois de chêne, quatre bâtis de commodes bombées de bois de chêne à deux tiroirs chacunes sans serure prisé cent vingt livres.” ↩︎

On the possibility of Oeben buying unfinished frames from Latz’s workshop, together with their mounts, to veneer later, see , 253. ↩︎

, 160–61, no. 43 (P. Leperlier). This piece is similar in form to the unstamped Quirinale commode with stylized floral marquetry, attributed to Latz and probably brought to Colorno by the Duchess of Parma in 1753, illustrated in , 237 and 239, no. 28. ↩︎

Cat. no. 1927.68. Gift of Archer M. Huntingon. ↩︎

See, e.g., a commode à la grecque by Oeben in the Museum’s collection, 72.DA.54. ↩︎

, 192–97, no. 55 (D. Alcouffe). ↩︎

It is tempting to speculate on the degree to which Oeben might have been inspired by other contemporary sources for floral marquetry. His 1763 inventory records a variety of botanical artworks, including prints and paintings, in various rooms of his home. The inventory is transcribed in . Relevant excerpts include “une vue de la décoration des illuminations de Versailles et une estampe représentant un bouquet de fleurs, sous verre blanc, dans leurs bordures de bois noircy” in a chamber overlooking the Cour des Princes; “cinq tableaux dessus de porte, dont quatre représentant des corbeilles de fleurs et les autres des animaux et oiseaux, tous peints sur toille [sic], le tout encastré dans la boiserie” of the chamber where Oeben died; and “un petit tableau peint sur toille sans bordure, représentant des fleurs” in a chamber also looking onto the Cour des Princes, all cited on pp. 315–16. A cabinet contained “trois autres petits tableaux représentants [sic] chacun un pot de fleurs sous verre blanc, dans leurs bordures de bois doré; un autre tableau peint sur bois, représentant une corbeille de fleurs, aussi dans sa bordure de bois doré; dix-sept estampes sous verre représentant différents sujets dans leurs bordures unyes, et deux tableaux peints sur toille sans bordures, représentant un pot de fleurs,” as described on p. 362. ↩︎

Writing to the Parisian miniaturist Pierre Noël Violet in 1781, the history painter Clément Louis Marie Anne Belle announced Tessier’s death in December of that year, describing him as “one of two flower painters” at the Gobelins and the son of an “ouvrier tapissier” at the Manufactory. Belle to Violet, December 14, 1781, cited in , 66–68. The letter identifies the other Gobelins flower painter as Maurice Jacques, who died in 1784 at seventy-two years of age. ↩︎

Taking into account the 1755 date of the manuscript version of the Livre de principes de fleurs and considering the possibility that it was printed in Paris as early as that year, at least two Chéreau widows then associated with the business Aux deux Piliers d’or in the rue Saint-Jacques could have overseen the publication of Tessier’s book. Geneviève Marguerite Chéreau, wife and first cousin of the printer and engraver François II Chéreau, was widowed in February 1755. François II inherited Aux deux Piliers d’or from his father; Geneviève Marguerite continued to operate it after his death in February 1755 and continued to do so until 1768. However, her mother-in-law, Marguerite Étiennette Caillou, widow of the famed printer François I Chéreau since 1729, also assisted her son in his endeavors at Aux deux Piliers d’or and did not die until April 1755. See , 378–79. This runs counter to Chastang, who identifies Anne Louise Chéreau, née Foy de Valois, as the widow of François II Chéreau and the likely publisher of the Livre as early as 1755 (, 115); and Anne Louise Foy de Valois/Vallois was also a woman engraver but married François II Chéreau’s son Jacques-François in 1769. She was never a widow as she died in childbirth in 1771, predeceasing her husband by over twenty years (, 378). ↩︎

See . The undated Livre de corbeilles et vases de fleurs was published by Jacques-François Chéreau for Tessier, probably around 1770. This book contains illustrations of flowers in baskets and vases by Tessier engraved by Jean-Jacques Avril. ↩︎

, 356. These marquetry flowers are immediately preceded by “un dessein en bois nué et découpé, représentant trois vaches, une chèvre et un bouvier apuyé contre une masure, un corps de corbeille de 5 pouces de haut, un autre petit corps de corbeille de 2 pouces et demy de haut, aussy en bois nué et découpé, deux débris de masure découpés et ombrés en bois blanc du même dessein.” ↩︎

Acc. no. 1114-1882. , 314, pl. 96. ↩︎

Acc. no. BK-16662. , 174–77, no. 40. ↩︎

, 258. ↩︎

A commode in the Frick Collection (acc. no. 1918.5.71) bears witness to this practice. The commode was completed in the early 1780s. Riesener shortened this piece’s legs before it was delivered to Marie-Antoinette’s apartments in the Tuileries shortly before the fall of the monarchy. In addition to altering the commode’s dimensions, Riesener changed the mounts and added a new marquetry panel that he both signed and dated 1791. ↩︎

French and Company invoice, January 27, 1972, in the files of the Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

Correspondence with Leon J. Dalva, October 15, 1993, in the files of the Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

Correspondence with Leon J. Dalva, October 15, 1993, in the files of the Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

Correspondence with John Partridge, 1974, in the files of the Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

French and Company invoice, January 27, 1972, in the files of the Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

French and Company invoice, June 27, 1972, in the files of the Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

. ↩︎

. ↩︎

, vol. 3, 795. ↩︎

. ↩︎

, vol. 3, 797. ↩︎

; . ↩︎

Bibliography

- 18th Century: Birth of Design 2014

- 18th Century: Birth of Design: Furniture Masterpieces 1650–1790. Exh. cat. Paris: Éditions Faton, 2014.

- Baarsen 2013

- Baarsen, Reinier. Paris 1650–1900: Decorative Arts in the Rijksmuseum. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, with Rijksmuseum, 2013.

- Bremer-David 2011

- Bremer-David, Charissa, ed. Paris: Life & Luxury in the Eighteenth Century. Exh. cat. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2011.

- Bremer-David et al. 1993

- Bremer-David, Charissa, et al. Decorative Arts: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue of the Collections of the J. Paul Getty Museum. Malibu, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1993.

- Briganti 1965

- Briganti, Chiara. “Comment Madame Infante a meublé sa résidence de Parme.” Connaissance des Arts 161 (July 1965): 48–59.

- Chastang 2007

- Chastang, Yannick. “Louis Tessier’s Livre de principes de fleurs and the Eighteenth-Century Marqueteur.” Furniture History 43 (2007): 115–26.

- Chastang 2001

- Chastang, Yannick. Paintings in Wood: French Marquetry Furniture. London: Wallace Collection, 2001.

- Eriksen 1974

- Eriksen, Svend. Early Neo-Classicism in France. London: Faber and Faber, 1974.

- Forray-Carlier 2000

- Forray-Carlier, Anne. Le mobilier du musée Carnavalet. Paris: Éditions Faton, 2000.

- Guiffrey 1899

- Guiffrey, Jules. “Inventaire de Jean-François Oeben 1763.” Nouvelles archives de l’art français, 3rd ser., vol. 15, 298–367. Paris: Noël Charavay, 1899.

- Hawley 1979

- Hawley, Henry. “A Reputation Revived.” The Connoisseur 202, no. 813 (November 1979): 176–82.

- Hawley 1970

- Hawley, Henry. “Jean-Pierre Latz, Cabinetmaker.” Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 57, no. 7 (September–October 1970): 203–59.

- Hickel 1963

- Hickel, Erika. Chemikalien im Arzneischatz deutscher Apotheken des 16. Jahrhunderts, unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Metalle. Braunschweig: Institut für Geschichte der Medizin, 1963.

- Jal 1872

- Jal, Augustin. “Chereau.” Dictionnaire critique de biographie et d’histoire. Paris: Henri Plon, 1872.

- Kjellberg 1989

- Kjellberg, Pierre. Le mobilier français du XVIIIe siècle: Dictionnaire des ébénistes et des menuisiers. Paris: Éditions de l’Amateur, 1989.

- “Lettres inédites” 1907

- “Lettres inédites d’artistes du XVIIIe siècle.” Archives de l’art français, vol. 1. Paris: Société de l’histoire de l’art français, 1907.

- Mudge et al. 2010

- Mudge, Mark, Carla Schroer, Graeme Earl, Kirk Martinez, Hembo Pagi, Corey Toler-Franklin, Szymon Rusinkiewicz, et al. “Photography-Based Digital Imaging Techniques for Museums.” Paper presented at VAST International Symposium on Virtual Reality, Archaeology and Cultural Heritage, Paris, September 2010.

- Paulin 2009

- Paulin, Marc-André. “A propos de la restauration du secrétaire à cylindre en nacre de Marie-Antoinette à Fontainebleau: Évolution et dégradation du placage en ‘satiné gris argenté’ du XVIIIe siècle à nos jours.” Bulletin de la Société de l’histoire de l’art français, Année 2008 (2009): 177–98.

- Paulin 2015

- Paulin, Marc-André. “L’art de la couleur selon Jean-Henri Riesener.” Bulletin du Centre de recherche du château de Versailles [online edition] (2015). http://journals.openedition.org/crcv/13350.

- Pradère 1989a

- Pradère, Alexandre. French Furniture Makers: The Art of the Ébéniste from Louis XIV to the Revolution. Malibu, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1989.

- Ramond 2000a

- Ramond, Pierre. Masterpieces of Marquetry. Vol. 2, From the Régence to the Present Day. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2000. Originally published as Chefs-d’oeuvre des marqueteurs. Vol. 2, De la Régence à nos jours. Dourdan: Éditions H. Vial, 1996.

- Roubo 1774

- Roubo, André Jacob. L’art du menuisier ébéniste. Paris: L. F. Delatour, 1774.

- Stratmann-Döhler 2002

- Stratmann-Döhler, Rosemarie. Jean-François Oeben, 1721–1763. Paris: Éditions de l’Amateur and Perrin & Fils, 2002.

- Verlet 1966

- Verlet, Pierre. La maison du XVIIIe siècle en France: Société, décoration, mobilier. Paris: Baschet, 1966.

- Wilson and Hess 2001

- Wilson, Gillian, and Catherine Hess. Summary Catalogue of European Decorative Arts in the J. Paul Getty Museum. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2001.

| words