15. Writing table (bureau plat)

- French (Paris), ca. 1745–49

- Attributed to Joseph Baumhauer (French, died 1772; ébéniste privilégié du Roi, ca. 1749)

- White oak* and ash* carcass veneered with bloodwood*; drawers of white oak; gilt bronze mounts; brass and iron hardware and lock; leather top

- H: 2 ft. 7 1/16 in., W: 5 ft. 11 3/8 in., D: 3 ft. 3 5/8 in. (78.9 × 181.3 × 100.6 cm)

- 71.DA.95

Description

This writing table of rectangular shape is supported on four cabriole legs that are five-sided in section. The table has five drawers, two of them hidden, all accessed from the front and with the central drawer recessed (fig. 15-1). The front of the desk is replicated on the back, however, with false drawer fronts. The top of the desk is set with three pieces of dark-colored leather cut to a conforming shape and tooled with a foliate scroll design with traces of gilding. An undulating and partly stippled gilt bronze frame molding surrounds the desk’s top.

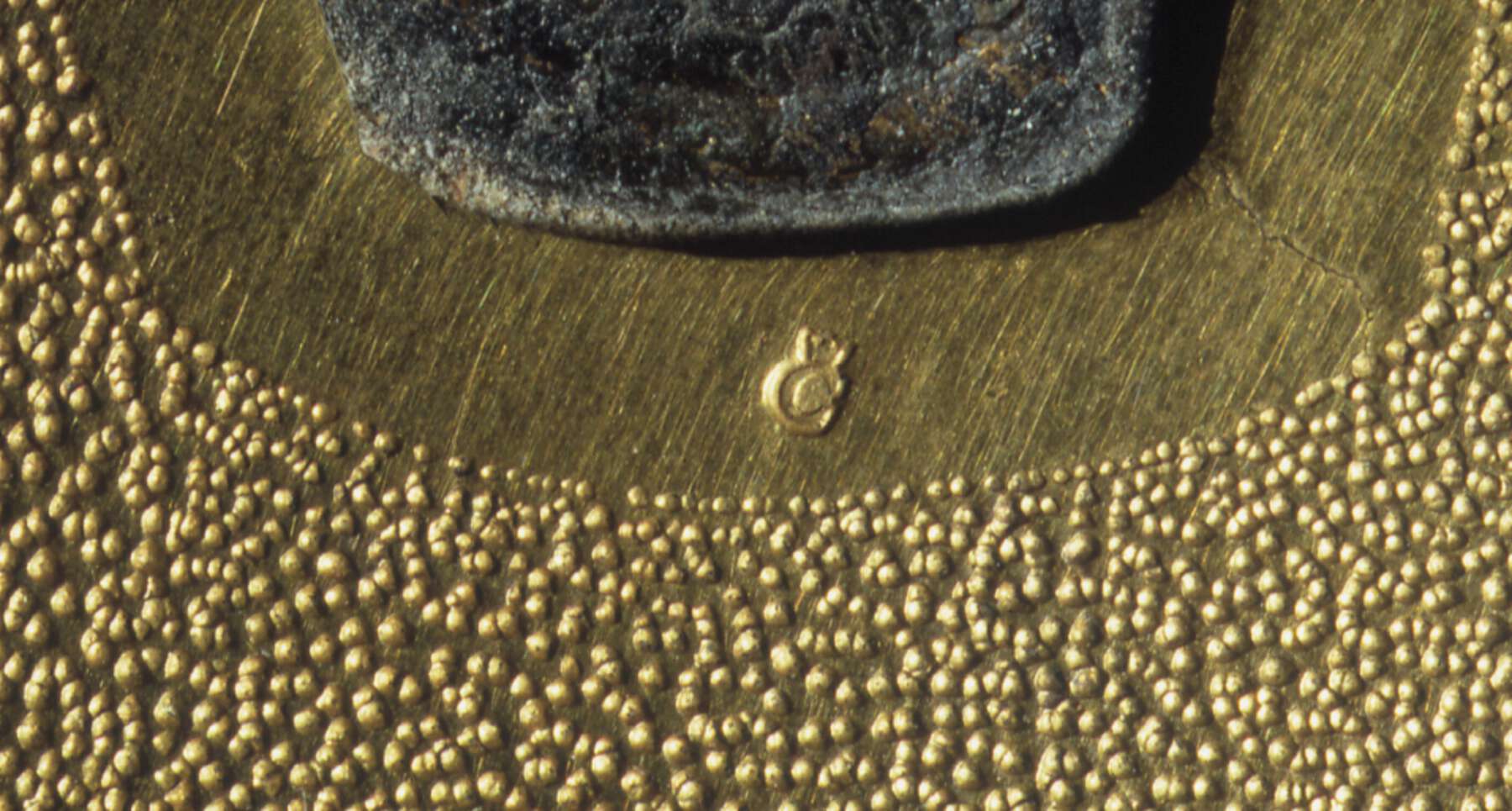

The white oak and ash carcass of this large rectangular desk is veneered with bloodwood. Wave-cut sections are used on the three drawer fronts, side panel insets, and back, with the legs veneered with pieces forming a chevron pattern. Thin, segmented frames follow along the desk’s lower edges and down the five sides of each leg. Shaped to follow the desk’s contours, a series of flat gilt bronze frames, burnished and stippled, are screwed over the veneer to delineate the drawer fronts and side panels (fig. 15-2). Most of the framing mounts are marked with a crowned C. The simple framing mounts set off the more sculptural rococo mounts, all of which also bear crowned C marks.

Each corner of the desk features an imposing gilt bronze mount in the shape of a robust shell formation at the top. Bordered by sinuous, leafy scrolls, these exuberant corner mounts descend down the desk’s legs, tapering into vegetal chutes that terminate in delicate shell and C-scroll sabots. The pulls on the two matching side drawers take the form of three-dimensional foliate scrolls, which lead into an exuberant pierced assemblage of rococo scrolls and garlands flanking the slightly recessed central drawer (fig. 15-3). This drawer, which is slightly wider than those on each side, features a functional double-throw lock. It has a keyhole escutcheon in the shape of a frilled shell set within a pair of foliate C-scrolls connected by two more abstract, shell-like motifs. Two scrolling drawer pulls extend from both sides of the escutcheon. The three front drawers conceal two secret, narrow drawers, one on each side of the central drawer.

A pierced gilt bronze mount is positioned at the center of the desk’s side panels. This asymmetrical cartouchelike mount, which adopts the line of the desk’s lower edge, takes the form of a large shell ornament set within a mass of foliate C-scrolls and floral garlands.

Marks

All sculptural mounts and most border mounts are stamped with the crowned C (fig. 15-4), indicating a date between 1745 and 1749.1

Commentary

The table is not stamped with a maker’s name, but it is attributed to Joseph Baumhauer on the basis of a closely comparable table stamped “JOSEPH” sold at auction in Paris in 1906 from the collection of Basil Kotschoubey (fig. 15-5).2 In the preface to the sale catalogue written by Léon Roger-Milès, that table is stated to have come from the collection of Count Alexei Razumovsky, the purported morganatic husband of Empress Elizabeth of Russia.3 While the mounts on the Kotschoubey table are all apparently of the same model as those found on the Museum’s table, the lower profile differs, and the central drawer front is flat, both horizontally and vertically. The elaborate kneehole mounts do not extend below the drawer frame but are more or less contiguous with it. The 1906 sale catalogue makes no mention of crowned Cs, but at this date their presence may have been overlooked or their meaning unknown to the cataloguer. The table did not apparently have secret drawers or special locking systems. It is not possible to see the arrangement of the veneers in the poor photograph, and the catalogue merely gives the description “en bois de placage.” The table was sold for 53,500 FF to a Monsieur Pauline.4 Its present whereabouts are unknown.

Figure 15-5

Figure 15-5A second table bearing mounts of the same model is in the musée du Louvre.5 It was given by René Grog in 1972, and its previous history is not known. The mounts and the carcass are unstamped, and it contains only three drawers. The lower profile differs from the Museum’s and the Kotschoubey table in that it is “hipped” in the area below either side of the central drawer, but like the Museum’s table the elaborate kneehole mounts extend below the plain framing mounts of the drawer fronts to touch the thin profile molding below. The mounts are all set on areas of amaranth, which outlines them. The rest of the surface area is veneered with bloodwood, with the grain set diagonally.

A third bureau plat in the Louvre, formerly thought to be stamped “Séverin,” resembles the Museum’s example in almost all respects—construction, secret drawers, locking systems, veneers, and mounts—with the exception being the kneehole mounts, which are of a considerably simpler model.6 Another bureau plat of this model and construction is in the musée de Soissons.7 Although it is stamped “M.CRIAERD” (master in 1738) twice, it is considered by Alexandre Pradère to be a copy of that in the Louvre.8 Indeed nineteenth-century copies of the so-called Séverin table exist, stamped with the names of such makers as Durand,9 Dasson,10 Beurdeley,11 and Krieger.12 Numerous unstamped examples have passed though the market, mounted in the same manner but, according to the catalogue descriptions, containing only three drawers each.

The veneers on the Museum’s table are laid with a mixture of straight grain, diagonally set marquetry on the upper case, wave-cut marquetry on the drawer fronts and side panel insets, and chevron arrangements on the legs. The former technique was used by Joseph Baumhauer on a commode bearing his stamp in the Fine Art Museums of San Francisco, Legion of Honor (see cat. no. 16), and on the so-called Séverin table in the Louvre. With the exception of those found at the upper corners and the feet, the mounts on these bureaux plats are not found elsewhere. Models of these corner mounts can be seen on a commode stamped “HANSEN,” for Hubert Hansen (master in 1747), again in the Fine Art Museums of San Francisco, Legion of Honor.13

The Museum’s table was first published in 1907, in an album reviewing an exhibition held in Saint Petersburg in 1904. This exhibition of European and Russian decorative arts at the Stieglitz Museum of Decorative and Applied Arts was sponsored by Empress Alexandra Feodorovna for the benefit of the war wounded. The table then belonged to the tsar’s cousin Helene, princess of Saxe-Altenburg. In the catalogue written by Adrien Prachoff,14 the table is described as being the “perle de la collection,” as having always been in the Chinese Palace at Oranienbaum, and belonging originally to Catherine II.15 Prachoff noted that the bronzes were stamped with “un poinçon parisien” and stated that this mark was used on objects made in Paris in 1743–44. At this time most historians were suggesting that the crowned C mark stood for the bronzier Jacques Caffieri. Prachoff was in advance of his time in recognizing that this was at least a datable tax stamp.16

The table was also published by Denis Roche in 1913 in his Le Mobilier français en Russie.17 In the introduction of the book he discusses a bureau plat with a bout de bureau, serre-papiers, and clock that was delivered to the empress Elizabeth as a gift from Louis XV.18 They were registered in the Présens du Roi of May 3, 1745:

Reçu du s.r Hébert un bureau de cabinet de 6 pieds de long sur 3 de large, en bois violet à compartimens, contourné, orné de chutes, pieds, cadres & quarts de rond, de bronzes réparés et dorés d’or moulu.

Plus, une armoire allant au bout dudit bureau, aussi de bois violet travaillé en fleurs et compartimens, et orné de même de bronzes réparés & dorés d’or moulu.

Plus, un serre-papiers du même goût, avec ses portes garnies de glaces.

Finalement, une pendule assortissante, et ornée de figures & autres accompagnemens dorés d’or moulu.

Toutes lesquelles choses lui avoient esté ordonnées pour un présent de sa Majesté à l’Impératrice de Russie, et reviennent avec les caisses dans lesquelles elles ont été emballées, à la somme de sept mille deux cens cinquante cinq livres, suivant le mémoire qu’en a fourni led[it] Hébert, de lui signé et certifié veritable, cy . . . 7255 [livres].19

The whereabouts of the royal gift, veneered with floral marquetry, remains unknown.

A serre-papiers stamped “JOSEPH” and with mounts struck with the crowned C, now placed on a bout de bureau by Bernard II van Risenburgh (see cat. no. 3) and bearing the trade label of Darnault, is in the Hermitage (fig. 15-6).20 It is suggested by Alexandre Pradère that the serre-papiers was originally placed on the Museum’s table.21 This stamped serre-papiers and the Museum’s bureau plat, both bearing mounts struck with the crowned C, must be among the earliest objects produced by Joseph Baumhauer.

Figure 15-6

Figure 15-6The revolutionary government seized the desk from Helene during the Russian Revolution, and it was nationalized in 1919. The Soviet government then sold it to the Duveen Brothers in 1931. Joseph Duveen did not purchase the table directly from Russia but from a Russian dealer, “M. Iljin,” in Berlin.22 The transaction is discussed in a letter to New York from Paris dated November 17, 1931:

We called to see Iljin when we were in Berlin. [ . . . ] He then asked us to make him an offer for the remaining pieces. [ . . . ] [H]e insisted [ . . . ] so we made him an offer of $16,000 for the vases and the inkstands including the fine Louis XV table from Oranienbaum. He said our offer was ridiculous and impossible for him to accept, as the valuation of his experts for these pieces was $28,500. We had a long argument over the matter, but we told him that we could not increase our offer. He came down to $18,000, then to $17,000, but we would not budge and prepared to leave. He then put the matter to a vote between himself, the Berlin director and the Leningrad director. Two voted “for” and one “against” so he accepted our offer.23

Duveen set aside the bureau plat for Anna Thomson Dodge (1871–1970), who was in the midst of building her mansion Rose Terrace in Grosse Pointe Farms, Michigan, just outside of Detroit. The table, together with volumes 1 and 2 of Denis Roche’s book Le Mobilier français en Russie, is included in a list of “Goods Shipped to Detroit” dated January 10, 1934.24 It was placed in the hall of Rose Terrace, which opened in 1934.25 An invoice dated August 27, 1935, shows that Mrs. Dillman (Anna Thomson Dodge) paid Duveen $72,000 for the table.26

Provenance

1745–62: possibly Empress Elizabeth of Russia, 1709–1762, given to her by King Louis XV of France, 1745, and then by inheritance to Catherine II of Russia, 1762;27 1745–63: or possibly Count Mikhail Illarionovich Vorontsov, Russian, 1714–1767 (Vorontsov Palace, St. Petersburg, Russia), sold to Empress Catherine II of Russia with the Vorontsov Palace, 1763; 1762 or 1763–: Empress Catherine II of Russia, 1729–1796;28 by 1904–19: Helene, duchess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, princess of Saxe-Altenburg, Russian, 1857–1936 (Cabinet de la Souveraine, Chinese Palace, Oranienbaum, near St. Petersburg, Russia), seized by the revolutionary government and nationalized during the Russian Revolution, 1919;29 1919–31: Soviet government, sold through Nikolai Iljin, one of the heads of the Antikvariat, to Duveen Brothers, Inc., in Berlin, Germany, 1931;30 1931–34: Duveen Brothers, Inc., sold to Anna Thomson Dodge, delivered in 1934;31 1934–70: Anna Thomson Dodge, American, born Scotland, 1871–1970 (Rose Terrace, Grosse Pointe Farms, Michigan), upon her death, held in trust by the estate, 1970;32 1970–71: Estate of Anna Thomson Dodge, American, born Scotland, 1871–1970 [sold, Highly Important Collection of French Furniture and Works of Art, Christie, Manson & Woods, London, June 24, 1971, lot 98, through French and Company to the J. Paul Getty Museum].33

Exhibition History

L’Exposition rétrospective d’objets d’art, musée du baron Stieglitz (Saint Petersburg), February 1–April 30, 1904; French Furnishings of the Eighteenth Century, Toledo Museum of Art (Toledo), December 3– 31, 1933; The J. Paul Getty Collection of French Decorative Arts, Detroit Institute of Arts (Detroit), October 3, 1972–August 31, 1973.

Bibliography

, 229, 231–32, 234, pl. 7 ; , vol. 1 (1913), 13–14, pl. XVIII; , no. 58; , viii–x, n.p., ill. ; , ix and unpaginated entry; , 173–74; , 88–89, fig. 12, ill.; , 35–36, fig. 3; Christie’s London, Anna Thomson Dodge sale, June 24, 1971, 79–80, lot 98, ill.; , 58–59, fig. 31; , 131; , 16, 19, fig. 3; , 245; , 50–51, no. 64; , 35, no. 61; , 76 n. 6, under no. 12, entry by Florian Knothe.

- G.W.

Technical Description

This bureau plat is an extraordinary example of the finest craftsmanship the eighteenth century had to offer in cabinetmaking, mechanical ironwork, and gilt bronze fabrication. The structure is made primarily of white oak, with some ash used in the construction of the top. The four legs, running from the floor to the top of the case, are each made up of two boards laminated together to form the large mass (approximately 4.5 x 4.5 in.) from which the profile was shaped. The inside corners of the legs, below the level of the case bottom, are treated in an unusual manner. Each has a V-shaped channel cut into the inner face, running from the floor to the bottom of the case (fig. 15-7). Near the top of the leg, a wedge-shaped section was left protruding into the channel, allowing the leg to have a square section at the level of the case.

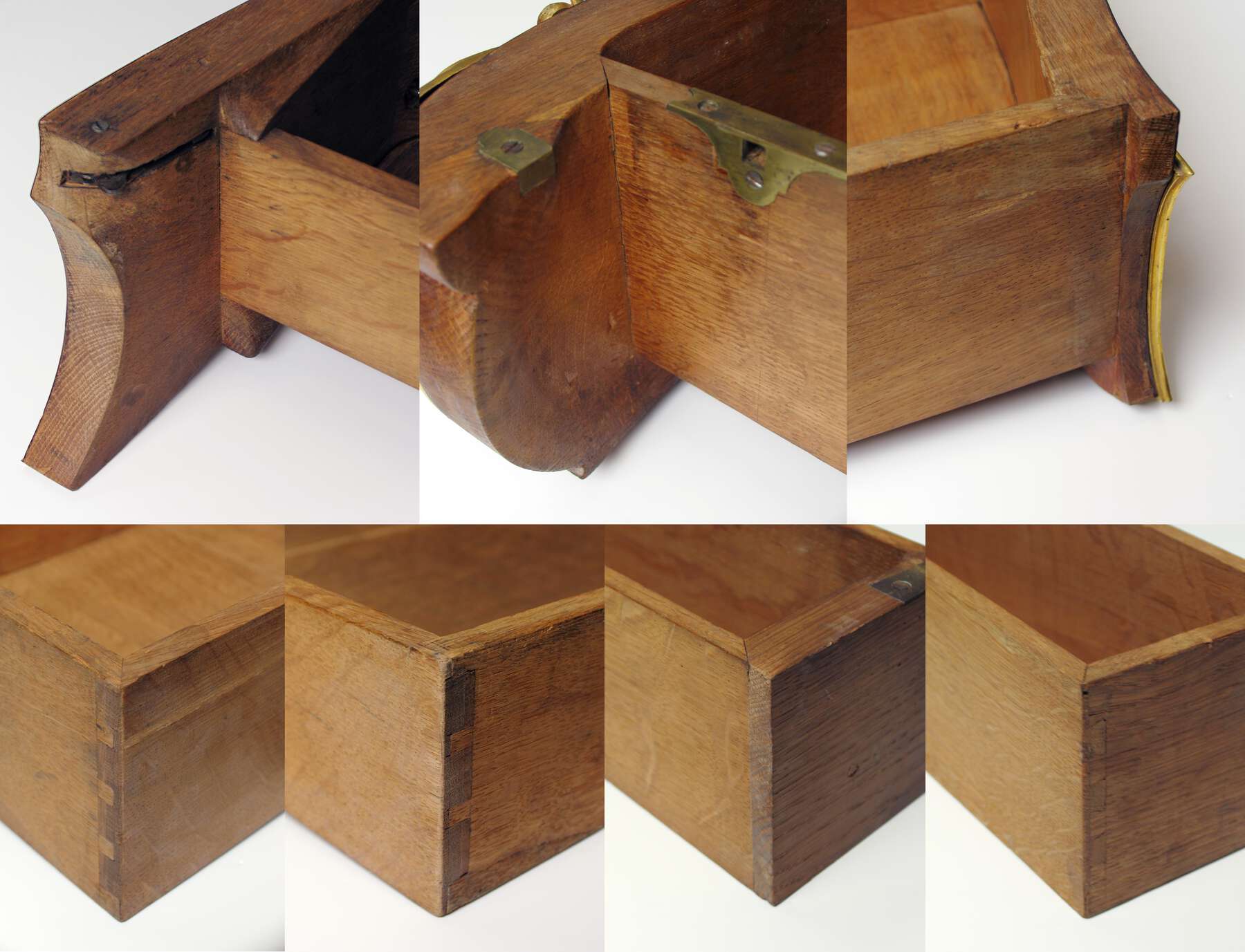

The side and rear frieze rails are connected to the legs with shouldered mortise-and-tenon joints. The rear frieze rail is constructed in a highly unusual manner. It is made of five separate pieces; a recessed center section that has been extended at either end with 6-in.-long blocks, attached with massive finger joints (fig. 15-8). Two swelling end sections are glued to the outer face of these connecting blocks, extending the rail to its full length.

Figure 15-8

Figure 15-8The table’s case bottom is made as a two-tiered frame-and-panel construction, with an upper tier at the center and lower tiers at the sides (fig. 15-9). The side rails are joined to the front and rear legs with mortises and tenons. The massive 2-in.-thick front and rear rails are joined to the side rails (not the leg posts) at a slightly canted angle, probably using mortises and tenons. These long rails are stepped on their upper faces to form the levels on which the drawers ride, while the bottom faces of the rails have a curved, gradual transition between the levels. The front and rear rails are built out on their exterior edges with several glued-on blocks of wood, three along the rear and four along the front. The blocks closest to the ends are joined to the leg posts with double mortises and tenons.

Figure 15-9

Figure 15-9The medial rails of the bottom frame appear to be secured with mortise-and-tenon joints. The two side panels are each made of two boards glued together on edge, while the larger central panel is made of five boards; the grain of all three panels runs from front to back. The entire bottom assembly is housed in a rabbet cut into the lower edges of the frieze rails.

The central drawer compartment is extremely solidly constructed and provides a great deal of support to the central portion of the bureau plat. The compartment may be thought of as two boxes made of thick oak boards, one at the front of the desk and another at the rear. The raised center sections of the case bottom rails serve as the bottoms for both boxes. The front box, which forms the openings for the center and secret drawers, is built with four uprights (fig. 15-10) all of which have their grain running vertically. The outermost uprights are connected to the horizontal box top with a set of dovetails and to the case bottom with mortises and tenons. The inner pair of uprights is joined to the top with four transverse through-tenons and at the bottom with mortise-and-tenon joints. The construction of the rear box is identical to that of the front, with the exception that the outer uprights have been omitted. Transverse upright boards, with the grain running front to back, connect the front and rear boxes and separate the central drawer compartment from the secret drawers.

Figure 15-10

Figure 15-10The front and rear box constructions may act as a sort of structural truss, stiffening the structure and helping to limit sagging of the bureau plat at the center. Currently, the total downward deflection of the top at the center is less than 5 mm.

Above the center drawer, and between the tops of the front and back boxes, there is a two-part sliding dust panel (fig. 15-11). The two panels, each of which has a long, thin rail glued to its top, are able to slide to the left and right but only if the side drawers are pulled nearly all the way out. The purpose of this highly unusual arrangement is not entirely clear. It is possible that the small space between the dust panels and the top (only about 1.5 mm deep) could have been designed as a secret compartment for documents; however, the space is awkward to access, and any document pushed deeply into the cavity would be nearly impossible to retrieve without removing the top.

Figure 15-11

Figure 15-11The drawers of the bureau are a tour de force of the cabinetmakers’ art. They are made using an extraordinary variety of sophisticated dovetail types, the complexity and inventiveness of which far exceed the bounds of necessity. Made using highest-quality quarter-sawn white oak, the drawers incorporate lapped full-blind dovetails, lapped and mitered full-blind dovetails, reverse lapped and mitered full-blind dovetails, lapped half-blind dovetails, and lapped and mitered half-blind dovetails (fig. 15-12). The sides of the drawers are quite substantial at approximately 14 mm thick, and the upper edge is flat (not rounded or beaded). The drawer bottoms are approximately 9 mm thick and are rabbeted on the underside of the edges to form a tongue that is housed in grooves in the four sides of the drawer. This drawer construction technique was unusual at the time but represents an innovative and advanced method that was adopted widely in the following decades. The wood of the drawer bottoms is oriented with the grain running from side to side, except for the long, thin secret drawers where the grain runs from front to back.

Figure 15-12

Figure 15-12The single lock for the desk is a double-throw lock located in the center drawer. It appears to be original to the desk, though its manufacture, using a cast brass case and finial-capped screws and bolts, is atypical for the period. A secondary mechanism, actuated by the bolt of the lock, is inlaid into the top of the front box construction, above the central drawers (fig. 15-13). When the central lock bolt is thrown upward it pushes on the canted ends of two long iron push rods, which are thus forced outward toward either end of the table. The ends of these rods seat into brass strike plates mounted on the sides of the outer drawers, locking them simultaneously with the central drawer. When the central lock is unlocked, the iron push rods do not retract automatically. Rather, the rods must be retracted manually by pushing two iron tabs, discreetly located in recesses in the underside of the writing surface, just above the lock. A tertiary mechanism ensures that the lock bolt can be thrown shut only if all three of the primary drawers are in the fully closed position. Two long steel springs are inlaid behind the secondary mechanism; these push forward on short iron push rods that run from front to back above the secret drawer compartments on either side. When these rods are in their fully forward position small tabs on their inner sides block the secondary push rods from sliding outward to lock the side drawers; this in turn prevents the central lock from being thrown shut. When the side drawers are fully closed, the short push rods are forced back, the tabs shift out of the way, and the secondary push rods are free to slide outward as the lock bolt is thrown.

Figure 15-13

Figure 15-13When all three of the large drawers are open, the two secret drawers are relatively inconspicuous; their fronts are of plain unvarnished oak and, obscured in the shadows below the top, they appear to be part of the structure. In order to open these drawers, short iron tabs concealed in the back of the top corners of the central drawer front must be rotated outward, like the blade of a pocketknife, so that they point toward the secret drawers (see top left of fig. 15-12). When the central drawer is then closed again, the thin tabs slide precisely into the narrow gaps just above the secret drawers and hook onto brass catches on the tops of the drawer fronts. When the central drawer is retracted once again, the tabs pull open the secret drawers at the same time (see fig. 15-13).

The top of the bureau plat is of frame-and-panel construction with wide rails, made of ash, running the length of the table at the front and back (fig. 15-14). Why these two elements alone were made of ash is unclear. Ash is slightly less heavy than oak but otherwise has very similar mechanical properties.34 According to Roubo, writing in Paris about two years after this bureau plat was made, ash was little used in cabinetmaking except for small pieces.35 Viaux-Lauquin agrees that ash was rare in eighteenth-century Parisian cabinetmaking but that it was used in the regional furniture of eastern France, particularly Burgundy.36 With the exception of these two elements, the rest of the top is made of white oak. The division of the top into panels is unusual; the wide primary medial rail runs the length of the top, from end to end, rather than crossing the shorter width across the center of the top. Four short front-to-back rails further divide the top into one larger and two smaller panels. The panels themselves are of equal thickness to the rails and are supported with tongue-and-groove joints.

Figure 15-14

Figure 15-14The top is attached in such a way that it is possible for it to be easily removed. Four iron tabs protrude downward from the underside of the top along the rear edge. Each tab is pierced with an approximately 1-cm-diameter hole. Two similar tabs are mounted near the front on the underside of the top. These two are rotated 90˚ and are slotted rather than being simply pierced. When the top is put on the base the rear tabs align just forward of four round iron pins protruding from the rear frieze. The slotted front tabs drop into mortises in the front legs. When the top is slid toward the rear, the holes in the rear tabs capture the pins in the rear frieze rail and the front tabs engage a perpendicular iron pin in the legs, preventing the top from moving upward. Once the tabs are locked into position, the top is prevented from sliding forward again by means of screws through a pair of L brackets attached to each side of the central drawer compartment.

The veneered decoration of this writing table, a parquetry of quartersawn and oyster veneer, was identified by microscopic anatomy as bloodwood. It is in extremely good condition, with no obvious signs of replacement. The veneer has been stained with a red-brown pigmented stain, which is most evident under the corner mounts. It is unlikely that this was part of the original surface treatment as it reduces the natural contrast of colors in the wood. The stain may have been applied during a previous restoration treatment to compensate for light-faded veneer.

In typical rococo style, there is no clearly established aesthetic rule between the use of straight-grain veneer and oyster veneer. The sides of the writing table are decorated with oyster veneer (sawn at an oblique angle to the grain direction) assembled in the same manner as the commode attributed to Jean-Pierre Latz (see cat. no. 16) and framed with straight-grain quartersawn veneer. The front and back frieze rail of the writing table, the side drawers, and two side panels of the frieze rail (made to simulate two side drawers) are veneered with a zigzag pattern of straight-grain veneer. The front central drawer is veneered with a zigzag pattern of straight-grain veneer over its entire surface, except at its center where two pieces of oyster veneer are used behind the pierced mounts. The central back panel of the frieze rail, also simulating a drawer front, is veneered with oyster veneer similar to the sides of the writing table.

The oyster veneer marquetry of this desk is similar to that of the Latz commode. However, it is much simpler in its execution because of the limited height of the side panels and front drawer of this writing table. The veneer work beneath the large scroll and floral mounts on the fronts of the side drawers and on the rear frieze rail is incomplete; only the areas visible through the openings in the mounts are veneered. This may be viewed as an economical saving of expensive imported veneer or may have been a means of avoiding the challenging task of veneering the complex bombé form of the writing table.

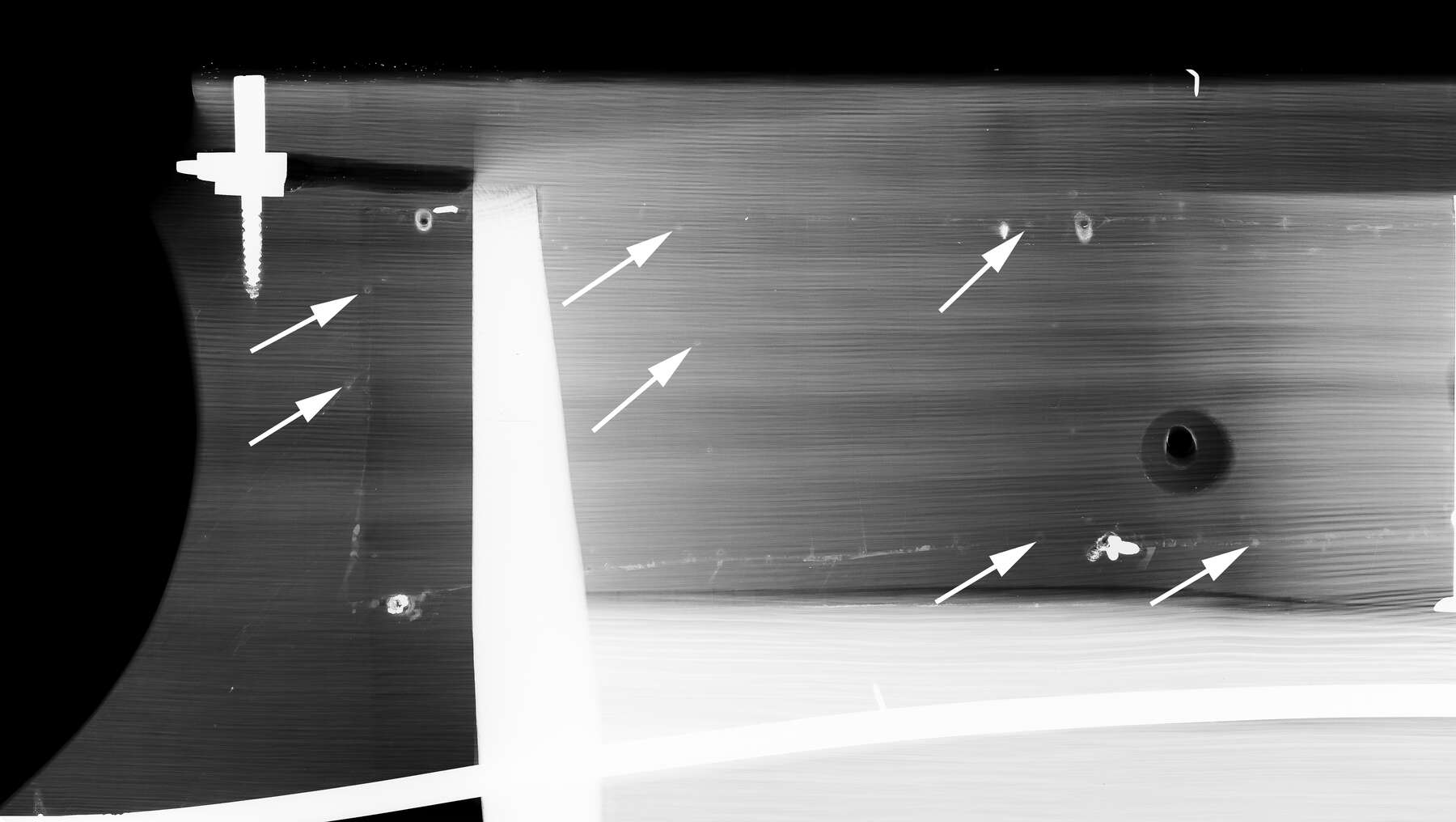

X-radiography reveals numerous small holes beneath the veneer (fig. 15-15). These holes are the result of the small nails, called veneer pins, that were originally placed alongside sections of veneer to stop them from sliding out of position during gluing and clamping. These holes are now only visible in X-radiographs and appear to be circular. Round pins are unusual for the period of manufacture of this writing table as most nails and pins produced at the time were hand-forged and were rectangular in shape. Small drawn iron nails (petit clous or épingles) were, however, available at the time, and their production is described in detail by Réaumur.37

Figure 15-15

Figure 15-15The mounts on this piece are cast and fitted with great skill. The chasing is equally fine, with a variety of matting techniques and punched embellishments, contrasted with burnished passages, that yield a lively and refined quality. All of the sculptural mounts as well as most of the border mounts, including the narrow beaded molding running along the lower edge of the frieze and the edges of the legs, are stamped with a crowned C.

The gilt bronze molding that surrounds the top of the bureau is mounted in four separate sections, two smaller sections above the central drawer compartment and two large U-shaped sections at either end. The molding is attached to the top with large-headed, handmade, iron machine screws that run upward through the edges of the top and into bridge-shaped anchors that have been soldered to the undersides of the mounts (fig. 15-16). Twenty-eight of the thirty existing machine bolts appear to be original; the heads are hand filed, and fine cracks along the length of the shafts suggest that they are made of wrought iron. The threading appears to have been formed by mechanical means or by a screw plate. The dimensions of the threading do not conform to any known nineteenth- or twentieth-century standard but rather conform well with units of measure commonly used in eighteenth-century France.38

Figure 15-16

Figure 15-16Twenty brass elements from the bureau plat were analyzed by X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) for alloy composition, including fifteen gilded bronze mounts, four pieces of brass hardware related to the lock mechanism, and one area of soldering metal behind a joint in the top molding. The alloys of the mounts are very typical in all respects of early to mid-eighteenth-century French castings. The alloys are also very consistent within the group, containing on average 17% zinc, 1% tin, and 1.5% percent lead, along with traces of iron, nickel, silver, and antimony. Likewise, the hardware and solder also appear consistent with eighteenth-century manufacture, with elevated zinc levels up to about 31%. These findings suggest that a nineteenth-century date for the mounts is extremely unlikely.

The black leather writing surface, with its tooled and gilt border decoration, is old, but it cannot be easily determined if it is original.

There are very few restorations evident on this bureau plat. The varnish on the exterior has doubtless been restored. In addition, six heavy iron straps have been installed to the top edge of the frieze rail to reinforce the structure. Four of these (one in each corner) appear earlier than two applied directly above the finger joints on the rear frieze rail, all of which are attached with relatively modern machine-made screws.39 The two latter straps are probably from a restoration that occurred in the early 1970s. Also, during the 1970s restoration, thin strips of light-colored wood were meticulously glued into any existing cracks where glue joints had separated.

By and large, however, the bureau plat is in an extraordinary state of preservation, with very minimal wear or evidence of use. This fact, along with the many unusual features of its construction and a relatively light oxidation of the interior surfaces, has led several knowledgeable observers to consider the possibility that the Getty bureau plat might be a later copy of the so-called Séverin table, now at the Louvre. The existence of several known nineteenth-century versions of this desk lends some credence to this idea.

In order to help confirm the age of the Getty bureau plat, a thorough dendrochronological (tree ring dating) study of the piece was undertaken. Nineteen individual pieces of wood from the structure and the drawers were identified as having areas of exposed end-grain suitable for analysis. High-resolution macrophotographs were made of the end-grain, and all visible rings were measured to the nearest hundredth of a millimeter. Analysis of the ring patterns in the wood shows that the youngest existing ring dates to 1713 and that the oak for the bureau plat grew in eastern France, probably in the region of Franche-Comté. Given that no sapwood remains on any of the pieces studied, these results imply that the earliest felling date for the tree(s) would be about 1730. Without sapwood, it is difficult to establish a terminus ante quem for the date of felling, but based on experience from other furniture studies it is extremely likely that the tree was cut before 1750.40 These results strongly suggest that the Getty bureau plat is an original eighteenth-century work and are in excellent accord with the date of 1745–49 proposed based on the evidence of the crowned C stamps.

- A.H.,

- Y.C.

Notes

, 22–23. An edict of Louis XV, registered with Parliament on March 5, 1745, required that all works old or new made with copper, in pure form or as part of an alloy, be stamped with a crowned C. This mark was canceled on February 4, 1749; therefore, objects with this stamp can be dated to between 1745 and 1749. ↩︎

For information on Joseph Baumhauer, see , 82–89; , 15–45; , 230–45. ↩︎

“Voici, par exemple, un bureau Louis XV, signé Joseph, avec son cartonnier, qui a appartenu au comte Rasoumowski, l’époux morganatique de l’impératrice Elisabeth de Russie, fille de Pierre le Grand.” Léon Roger-Milès, preface, Hôtel Drouot, Catalogue des objets d’art et d’ameublement composant la collection de M. B. Kotschoubey, April 13–16, 1906 (Paris: Hôtel Drouot, 1906), 9. The desk sold as lot 384, and on pp. 55–56 it is described as follows: “IMPORTANT BUREAU-PLAT du temps de Louis XV, de forme contournée, à quatre pieds cambrés, ouvrant à trois tiroirs à la ceinture, en bois de placage. Il est très richement orné de bronzes finement ciselés et dorés. Sur les pieds: chutes à rocailles et feuillages, baguette et sabots à volute; sur les tiroirs: baguettes d’encadrement moulurées, agrémentées de rinceaux feuillagés et fleuris dans lesquels se trouvent les entrées de serrures. Le dessus du meuble se profile d’un large quart de rond à moulures. Il porte l’estampille de Joseph, maître-ébéniste, dont on peut voir un meuble, de caractère analogue, au South Kensington à Londres. La même signature se trouve sur une commode en laque ayant fait partie de l’ancienne collection Ch. Stein (voir Émile Molinier, L’Histoire du mobilier français). (Restaurations, notamment dans l’ébénisterie.) Long., 1 m. 90; larg., 95 cent.; haut., 84 cent.” The cartonnier was sold as lot 385 and described as follows: “CARTONNIER du temps de Louis XV, de forme mouvementée, à quatre pieds, avec sept casiers, en bois de placage. Il est richement orné de bronzes dorés à rinceaux, feuillages et motifs variés, formant encadrements sur les côtés. Il repose sur un meuble, de même bois de placage, ouvrant à porte sur chacun des côtés également, orné de bronzes dorés. Ce cartonnier avec son support peut accompagner le bureau précédent. Dimensions du cartonnier: long., 86 cent.; haut., 64 cent. Dimensions du dessous du cartonnier: long., 95 cent.; haut., 88 cent.; prof., 40 cent.” A handwritten note in a copy of the auction catalogue in the collection of the Bibliothèque nationale de France details that the cartonnier sold to the vicomte de La Redoute for 12,700 francs. ↩︎

Hôtel Drouot, Catalogue des objets d’art et d’ameublement composant la collection de M. B. Kotschoubey, April 13–16, 1906 (Paris: Hôtel Drouot, 1906), 55. The photograph of the bureau plat is in a copy of the auction catalogue in the collection of the Getty Research Institute, and the handwritten note is in a copy in the collection of the Bibliothèque nationale de France. ↩︎

Acc. no. OA10452; , 46. ↩︎

Acc. no. OA7805. It was once reputed to have belonged to the abbé Terray. See , plate 814 (78 x 200 x 90 cm); , 87, illus. ↩︎

Inv. 993.9.2. See , plate 258 (79 x 199 x 98 cm). ↩︎

Correspondence with the author, September 20, 2000. ↩︎

Sotheby Parke-Bernet, Fine French Furniture, British & French Paintings [ . . . ], March 30, 1951 (New York: Sotheby Parke-Bernet, 1951), lot 152, signed F. Durand Fils (31 1/2 in. x 6 ft. 7 in.), with hidden drawers. Also Nouveau Drouot, Tableaux et sculptures, meubles et objets d’art du XIXe siècle, November 9, 1987 (Paris: Nouveau Drouot, 1987), lot 123, stamped “G. Durand”; no hidden drawers are mentioned in the sale catalogue (80 x 199 x 102 cm). A further copy was seen by the author in the gallery of the Parisian antiques dealer Pierre Lécoules, rue Taitbout, in 1975. It was fitted with hidden drawers and had levers to lock both them and the side drawers shut. ↩︎

Offered for sale, Sotheby’s, Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Works of Art and Furniture, March 1, 1991 (London: Sotheby’s, 1991), lot 188. Stamped “Henry Dasson 1888.” It did not contain hidden drawers (L: 6 ft. 6 in.). Sold again, Sotheby’s, Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Works of Art and Furniture, November 8, 1991 (London: Sotheby’s, 1991), lot 180. Another copy, stamped Dasson, was advertised by Pierre Lécoules, in Apollo 142 (December 1973): 130. ↩︎

Christie’s, Nineteenth Century Furniture, Sculpture, Porcelain and Decorative Objects, September 23, 1994 (New York: Christie’s, 1994), lot 2789. Stamped “A. Beurdeley à Paris.” It did not contain hidden drawers (31 x 57 x 32 1/2 in.; 78.7 x 144.7 x 82.5 cm). Another copy, stamped “Beurdeley,” was seen by the author in 1975 in the gallery of Pierre Lécoules. It contained hidden drawers. ↩︎

J. Mercier, D. Thullier, T. May, D. Soinne, and P. Deguines, Orfèvrerie – Céramique [ . . . ], March 26, 2000 (Lille: Mercier, Thullier, May, Soinne, Deguines, 2000), lot 409, signed “KRIEGER à Paris” on the bronzes and the lock plate. It contained hidden drawers (81 x 198 x 100 cm). Another sold at Christie’s, 19th Century Furniture and Sculpture, Christie’s, March 21, 2002 (London: Christie’s, 2002), lot 108. Undersurface of the carcass and lock plate signed “Krieger, Paris” (31 1/2 x 79 x 39 1/3 in.; 80 x 201 x 100 cm). A third sold at Millon et Associés, June 27, 2003 (Paris: Millon et Associés, 2003), no. 87. Stamped “KRIEGER” on the lock plate (80 x 177 x 82 cm). ↩︎

Acc. no. 1926.87. See , 130, fig. 5. ↩︎

, 229–31, pl. VII. ↩︎

See , 68–73. ↩︎

, 231. ↩︎

, vol. 1, pl. xviii. ↩︎

, vol. 1, 13–14. ↩︎

La Courneuve, Ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires étrangères, Archives diplomatiques, Registres des Présents du Roi, tome 2062, fol. 25v; on fol. 26r, under the date May 8, 1745: “Le bureau, l’armoire, le serre-papiers de la pendule décrite dans l’article cy-contre, après avoir été emballés dans quatre caisses diférentes [sic] ont été embarqués par ordre de M.r le marquis d’Argenson ministre et secrétaire d’État des Afaires [sic] étrangères, à adresser à M.r de la Bourdonnaye intendant de Rouen, avec une instruction pour la faire passer sûrement à Petersbourg sur un vaisseau neutre [?]; et M.r de la Bourdonnaye a accusé depuis la réception des dites quatre caisses bien conditionnées, tant à M.r le marquis d’Argenson qu’au S.r de Bazé [name difficult to read because of the archives’ stamp] et leur marquant les précautions qu’il a prises pour la sûreté de cet envoy, qui revenant comme il a esté expliqué cy contre à la somme de sept mille deux cents cinquante cinq livres. doit estre pareillement porté en dépense pour la susdite somme de cy 7255 [livres].” The desk is also mentioned in tome 2097, fol. 97r/v: “En 1745. Un bureau de cabinet de six pieds de long sur trois de large, en bois violet à compartimens, contourné, orné de chutes, pieds, cadres & quarts de rond, de bronze réparés et dorés d’or moulu. Une armoire allant au bout dudt. bureaux [sic] avec les mesmes ornemens. Un serre papier avec les mesmes ornements, avec ses portes garnies de glaces. Une pendule assortissante à l’Impératrice de Russie, le tout du prix de 7255 [livres].” It also appears in tome 2098, fol. 30v, on May 22, 1745: “Présent d’un bureau de cabinet envoyé en Russie de la valeur de 7255 [livres].” ↩︎

Acc. no. 434 M6. See , 206, figs. 1, 2; , 196. ↩︎

, 245. ↩︎

It is likely that “M. Iljin” was Nikolai Nikolaevich Ilyin (1887–1939?), who was chairman of the Antikvariat, or State Trading Office, from 1930 to 1935 and frequently traveled in that capacity to Germany, France, Britain, Austria, and the United States from 1930 to 1933. The Antikvariat was the agency that sold nationalized collections of art and antiques on the international market at the behest of the Soviet Commission for Accounting and Sales of State Funds. , 96–21, 345. ↩︎

Files regarding works of art: Pavlovsk Palace Collection, 1931–54. Duveen Brothers Records, 1876–1981 (bulk 1909–64). Getty Research Institute, 960015, box 271, folder 22. http://hdl.handle.net/10020/cifa960015. ↩︎

Collectors’ files: Dillman, Mrs. (Dodge), 2, ca. 1934, Duveen Brothers Records, 1876–1981 (bulk 1909–64), Getty Research Institute, 960015, box 442, folder 6. http://hdl.handle.net/10020/960015b442f005. ↩︎

Agis Salpukas, “An Era Ends as a Great Estate’s Trappings Go Up for Auction,” New York Times, Sept. 26, 1971. ↩︎

A copy of the invoice is in the curatorial file in the Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

La Courneuve, Ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires étrangères, Archives diplomatiques, Registres des Présents du Roi, tome 2098, fol. 30, Pierres et Bijoux des Présens du Roy, March 20, 1738–April 25, 1745. ↩︎

, 229–31. ↩︎

, 229–31. ↩︎

Files regarding works of art: Pavlovsk Palace Collection, 1931–54, Duveen Archives, Getty Research Institute, 960015, box 271, folder 22. ↩︎

Collectors’ files: Dillman, Mrs. (Dodge), 1, ca. 1925–33, Duveen Archives, Getty Research Institute, 960015, box 442, folder 5. ↩︎

Collectors’ files: Dillman, Mrs. (Dodge), 1, ca. 1925–33, Duveen Archives, Getty Research Institute, 960015, box 442, folder 5. ↩︎

French and Company invoice, June 28, 1971, in the files of the Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

, 8. ↩︎

, vol. 3, 784. ↩︎

, 107–9. ↩︎

, 53, pl. 2. ↩︎

The major diameter of the threaded sections (4.6 mm) is very close to two lignes, while the pitch or spacing of the threads (1.13 mm) is almost exactly two threads per ligne. ↩︎

Were this piece to have been stamped by its maker, the corner straps would likely have obliterated any trace. ↩︎

For details of the dendrochronological study, see the complete reports by Didier Pousset with Christine Locatelli and Arlen Heginbotham, on file in the Decorative Arts and Sculpture Conservation Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. Macrophotography for the study was done by Jack Ross of the Getty Imaging Services Department. ↩︎

Bibliography

- Catalogue . . . Anna Thomson Dodge 1933

- A Catalogue of Works of Art of the Eighteenth Century in the Collection of Anna Thomson Dodge. Detroit: Detroit Institute of Art, 1933.

- Alcouffe 1997

- Alcouffe, Daniel. “La Collection Grog-Carven entre au Louvre.” L’Estampille/L’Objet d’Art, no. 311 (March 1997): 38–47.

- Augarde 1987

- Augarde, Jean-Dominique. “1749, Joseph Baumhauer, ébéniste privilégié du Roi.” L’Estampille, no. 204 (June 1987): 15–45.

- Bendtsen and Ethington 1975

- Bendtsen, B. Alan, and Robert L. Ethington. “Mechanical Properties of 23 Species of Eastern Hardwoods.” USDA Forest Service Research Note. Madison, WI: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory, 1975.

- Bennett and Sargentson 2008

- Bennett, Shelley M., and Carolyn Sargentson, eds. French Art of the Eighteenth Century at the Huntington. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008.

- Boutemy 1973

- Boutemy, André. Analyses stylistiques et essais d’attribution de meubles français anonymes du XVIIIe siècle. Brussels: Université de Bruxelles, 1973.

- Boutemy 1957

- Boutemy, André. “BVRB et la morphologie de son style.” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 49 (May 1957): 165–74.

- Boutemy 1965

- Boutemy, André. “L’ébéniste Joseph Baumhauer.” Connaissance des Arts 157 (March 1965): 82–89.

- Bremer-David et al. 1993

- Bremer-David, Charissa, et al. Decorative Arts: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue of the Collections of the J. Paul Getty Museum. Malibu, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1993.

- Catalogue . . . Anna Dodge Dillman 1939

- Catalogue of Works of Art in the Collection of Anna Dodge Dillman. Vol. 1, Paintings, Tapestries, Furniture, and Objets d’Art. Detroit: Detroit Institute of Art, 1939.

- Champeaux 1890–91

- Champeaux, Alfred de. Portefeuille des arts décoratifs. Vol. 3, Troisième année, 1890-1891. Paris: A. Calavas, 1890–91.

- Champeaux 1896–97

- Champeaux, Alfred de. Portefeuille des arts décoratifs. Vol. 9, Neuvième année, 1896–1897. Paris: A. Calavas, 1896–97.

- Coleridge 1971

- Coleridge, Anthony. “Works of Art with a Royal Provenance from the Collection of the Late Mrs. Anna Thomson Dodge of Detroit.” The Connoisseur 177, no. 711 (May 1971): 34–36.

- Dreyfus 1924

- Dreyfus, Carle. “Bulletin des Musées.” Beaux-arts (March 15, 1924): 87–88.

- French Furnishings . . . 1933

- French Furnishings of the Eighteenth Century. Exh. cat. Toledo, OH: Toledo Museum of Art, 1933.

- Prachoff 1907

- Prachoff, Adrien. Album de l’exposition rétrospective d’objets d’art. Saint Petersburg: Golicke and Willborg, 1907.

- Pradère 1989a

- Pradère, Alexandre. French Furniture Makers: The Art of the Ébéniste from Louis XIV to the Revolution. Malibu, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1989.

- Réaumur 1761

- Réaumur, René Antoine Ferchault. Art de l’épinglier, par M. de Réaumur, avec des additions de M. Duhamel Du Monceau, et des remarques extraites des mémoires de M. Perronet . . . Paris: Saillant et Nyon, 1761.

- Rappe 1993

- Rappe, Tamara. “The History of the Furniture Collections in the Hermitage.” Furniture History 29 (1993): 205–16.

- Rieder 1980

- Rieder, William. “French Furniture of the Ancien Regime.” Apollo 216 (February 1980): 127–34.

- Roche 1912–13

- Roche, Denis. Le mobilier français en Russie: Meubles des XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles et du commencement du XIXe, conservés dans les palais et les musées impériaux et dans les collections privées. 2 vols. Paris: E. Lévy, 1912–13.

- Roubo 1774

- Roubo, André Jacob. L’art du menuisier ébéniste. Paris: L. F. Delatour, 1774.

- Semyonova and Iljine 2013

- Semyonova, Natalya, and Nicolas V. Iljine, eds. Selling Russia’s Treasures: The Soviet Trade in Nationalized Art 1917–1938. Paris and New York: M. T. Abraham Center for the Visual Arts Foundation in association with Abbeville Press, 2013.

- Verlet 1937

- Verlet, Pierre. “A Note on the ‘Poinçon’ of the Crowned ‘C.’” Apollo 151 (July 1937): 22–23.

- Viaux-Lauquin 1997

- Viaux-Lauquin, Jacqueline. Les bois d’ébénisterie dans le mobilier français. Paris: Léonce Laget, 1997.

- Wilson, Sassoon, and Bremer-David 1984

- Wilson, Gillian, Adrian Sassoon, and Charissa Bremer-David. “Acquisitions Made by the Department of Decorative Arts in 1983.” J. Paul Getty Museum Journal 12 (1984): 173–224.

- Wilson and Hess 2001

- Wilson, Gillian, and Catherine Hess. Summary Catalogue of European Decorative Arts in the J. Paul Getty Museum. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2001.

- Worsley 1989

- Worsley, Giles. “The Chinese Pavilion at Oranienbaum.” Country Life 183 (November 16, 1989): 68–73.