10. Writing table (bureau plat)

- French (Paris), ca. 1745–49, with nineteenth-century alterations

- By Bernard II van Risenburgh (French, after 1696–ca. 1766, master before 1730)

- White oak and white pine*, veneered with tulipwood*, stained pear*, and ebony*; drawers of walnut and white oak; gilt bronze mounts; brass, steel, and iron hardware and locks; replacement leather top

- H: 2 ft. 7 in., W: 5 ft. 4 1/2 in., D: 2 ft. 7 1/2 in. (78.7 × 163.8 × 79.6 cm)

- 78.DA.84

Description

This rectangular table with undulating sides has a top of conforming shape. It is supported on four cabriole legs that are five-sided in section. It contains three drawers, the central drawer being slightly recessed. Each drawer is fitted with an individual lock. Matching false drawer fronts are repeated on the back of the table. The top is covered with black leather edged in tooling in a scrolled and twisted rope design. The leather is surrounded by a broad frame of tulipwood bordered on either side by a narrow band of ebony.

Each rounded corner of the stepped gilt bronze frame of the top is overlaid with a clasp mount composed of a central leafy motif surrounded by C-scrolls, with a shell-like frame. Further C-scrolls surmount the arrangement, emerging from a central leafy bud. Each corner of the body of the table is set with a large pierced mount. The burnished frame of the cartouche is lined with small C-scrolls and wavelike borders. The aperture of the upper pierced shield-shaped section is lined with C-scrolls, and at the base of the mount an undulating leafy branch bearing flowers rises from a leafy whorl to fill the main pierced area. A further extension of the mount below the leafy whorl consists of a cabochon set on a foliate form that terminates in a small pendant of two buds. This section overlaps the bifurcated top of the leg mount, which is cast with pierced guilloche of decreasing size on a stippled ground, framed on either side by a flame motif (fig. 10-1).

At the center of each side of the table is a mount consisting of an undulating leafy plant carrying flowers and berries, rising from a berried leaf whorl (fig. 10-2). The arrangement is supported by two stippled foliate C-scrolls that follow the lobed lower profile of the table. To either side of the recessed central drawer is a large mount composed of two burnished scrolls lined with small C-shapes and containing a series of pierced oval guilloche alternating with small cabochons. Above is an arrangement of leaves carrying buds, and below is a further C-scroll similarly set with small C shapes and flame motifs set with cabochons, resting on two extending acanthus leaves.

The keyhole escutcheon of the middle drawer is centered by a shell surrounded by C-scrolls and leaves and surmounted by a leafy plinth, all arranged to form an asymmetrical assemblage. The outer drawers also carry keyhole escutcheons formed to serve as small handles. The escutcheon itself is pear shaped with a stippled ground. It is clasped by leaves on either side and surmounted by a berried knop. Another leafy cup containing a berry hangs below. Two ribbed and arching leaves form the handle.

The feet are shod with pierced gilt bronze sabots. The pierced cartouche of each is formed by two joined C-scrolls rising from an incurving foliate foot and supporting a small leafy bud. The interiors of the C-scrolls forming the cartouche are lined with small C shapes. The drawers and the sides of the table are set with simple flat burnished frames shaped to follow the contours of the drawer fronts and the profile of the lower edge. These also frame the central mount on either side of the desk. The body and the legs of the table are veneered with tulipwood, with ebony used for the top edge of the drawers.

Marks

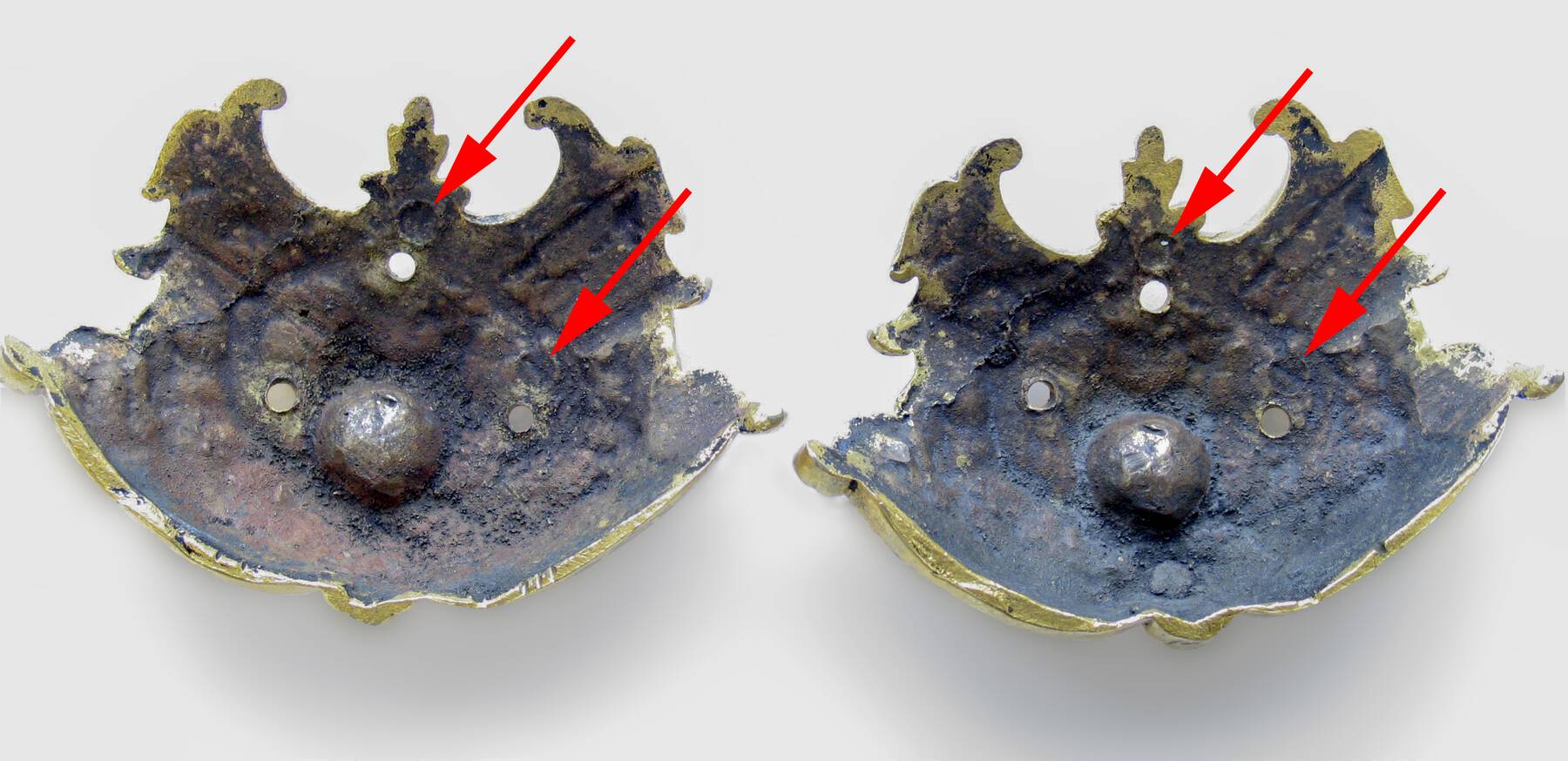

The table is stamped “B.V.R.B.,” for Bernard II van Risenburgh, with “JME,” for jurande des menuisiers-ébénistes, stamps on either side, on the top of both the right- and left-hand front leg stiles, and only visible when the top is removed (fig. 10-3). An effaced “B.V.R.B.” stamp is flanked by two “JME” stamps on the underside of the table on a rail under the left drawer (fig. 10-4). A number of gilt bronze mounts are stamped with the crowned C.1

Figure 10-3

Figure 10-3 Figure 10-4

Figure 10-4Commentary

The table is stamped “B.V.R.B.” on the horizontal surface on the top of the front left and right legs, beneath the top, as well as on the underside of the table on a rail under the left drawer.2 The stamps were discovered when the table was dismantled during conservation by H. J. Hatfield in 1973. In its size, profile, and gilt bronze mounts, the desk resembles two other bureaux plats also stamped “B.V.R.B.” One is in the collection of the Princely Collections, Liechtenstein (fig. 10-5).3 With the exception of the drawer handles, the central side mounts, and the corner clasps of the top, the mounts are of the same model and are struck with the crowned C.4 The drawer fronts and the sides of the table are veneered with end cut floral marquetry. The second table was offered for sale at Christie’s London in 1993 (fig. 10-6).5 Formerly in the collection of Baron Gustave de Rothschild (1829–1911), it is set with mounts of the same form, with the exception of the handles on the drawers, which are absent. In their place are simple keyhole escutcheons. Short trailing mounts attached to the scrolled corner mounts may be later additions. The mounts are struck with the crowned C.6 The fronts of the drawers and the sides of the table are set with panels of Japanese lacquer.

Figure 10-5

Figure 10-5 Figure 10-6

Figure 10-6It is possible that the Museum’s table was once decorated with Asian black lacquer in the same manner. The top interior edges of the drawers are veneered with bands of ebony (fig. 10-7), and the interior sides of the legs are veneered in ebonized pear, both elements that appear to be original. These features would have complemented the original lacquer panels. The broad flat frames surrounding the drawer fronts and the side friezes, which are of identical form to the Rothschild table mentioned above, now contain plain areas veneered with a wood of ill-chosen grain, likely added in the mid-nineteenth century. Thus the Museum’s table’s appearance has been significantly altered over time.7

Smaller bureaux plats for more intimate surroundings seem to have been introduced in the 1730s. Such a table was delivered to Louis XV’s private cabinet at Versailles in 1734.8 That table survives at Versailles today, and Christian Baulez has attributed it to the ébéniste Louis Marteau, who died in 1746.9 Although heavier in style, it does bear comparison to the Museum’s table in the design of two of its gilt bronze mounts, especially the corner mounts. These extend from double scrolls down the outer edge of the legs and are pierced with ovals of alternating large and small size down the entire length. The large mounts centering the sides of the table are in the form of flowering plants rising from concave grounds. They are of similar form to those found on Van Risenburgh’s table and may have been its inspiration.10

Even though lacquer may be lost from the drawer fronts, it appears that at least one of the combined escutcheons and handles on the side drawers and one of the asymmetrical escutcheon mounts on the center drawer of both the front and back of the desk are original. They are found in the same position on a table delivered by the marchand-mercier Thomas Joachim Hébert to the dauphin Louis-Ferdinand in 1745 for his Grand Cabinet at Versailles.11 Feet mounts of the same model are to be seen on a secrétaire en pente, also by Van Risenburgh, delivered by Hébert to the dauphine Maria-Teresa Rafaela of Spain for use in her private cabinet that same year.12

A nineteenth-century copy of the table stamped “EHB,” for Edward Holmes Baldock (1777–1845), was sold at auction in Los Angeles in 1978 (fig. 10-8).13 Close examination revealed flaws in its gilt bronze mounts in the same areas where crowned Cs are to be found on the mounts of the Museum’s table, showing that the latter was in Baldock’s possession and that a copy was made of it, casts having been taken of its mounts. It is the only known example of the dealer and “improver” making a direct copy of an object. As Baldock is listed in the London directories between 1808 and 1844, the Museum’s table must have been in London at some point during that span of years; it is possible that Baldock was responsible for the removal of the lacquered panels.

Figure 10-8

Figure 10-8Provenance

–1931: Henry Hirsch, English, died 1934 (23 Park Lane, W, London, England) [sold, The Important Collection of Old English Furniture, Fine Chinese Porcelain, French and Italian Furniture, and Objects of Art formed by Henry Hirsch, Esq., Christie’s, London, June 10–11, 1931, lot 171, to J. M. Botibol]; 1931–40: J. M. Botibol, in business 1920–53 (Hanway Road, London, England), sold to J. Paul Getty, 1940;14 1940–76: J. Paul Getty, American, 1892–1976, upon his death, held in trust by the estate, 1976; 1976–78: Estate of J. Paul Getty, American, 1892–1976, distributed to the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1978.

Bibliography

, ill. facing p. 56; , 171; , 166–67; , 38–42, figs. 2, 4–5, 7–8; , 139; , 51, no. 65; , 36, no. 62.

- G.W.

Technical Description

It is apparent that the Getty bureau plat is a heavily restored example of Van Risenburgh’s work, with at least three significant restoration campaigns identified. There is some evidence to suggest that major alterations were made as early as the second quarter of the nineteenth century, possibly including replacement of nearly half of the veneer, a substantial number of the mounts, and the bureau plat’s top. These restorations may be associated with the London dealer and “improver” Edward Holmes Baldock.

The top front rail, which runs above the drawers, is connected to the legs with a pair of open-faced dovetails at each end (see fig. 10-3). The bottom rail does not run in one piece from one leg to the other but is made of three separate horizontal sections linked by two short vertical blocks located between the drawers. At either end, the composite rail is connected to the legs with sliding dovetails that extend through the full thickness of the legs. The vertical blocks between the drawers are connected to the top front rail with two dowels that pass through the upper rail and are visible from the top (fig. 10-9). This is an unusual method of construction for mid-eighteenth-century Paris. The three horizontal sections of the bottom rail appear to be attached to the vertical blocks with mortise-and-tenon joints although, even after examination with X-radiography, the exact configuration could not be determined. The bottom rail underneath the middle drawer is elevated about one inch higher than the side rails, accommodating the reduced height of the middle drawer. Additional blocks of oak were glued to the bottoms of the horizontal rails next to the legs and the vertical blocks to achieve the curved form of the lower rail.

Figure 10-9

Figure 10-9The case bottom is constructed in a tripartite frame-and-panel construction (fig. 10-10). At the front, the composite lower rail below the drawer fronts doubles as the front rail of the case bottom, with the rear edges of each of the three horizontal sections grooved to receive the panels. The rear rail, also acting as the rail for the rear rail for the case bottom, is similarly grooved. The case bottom’s side rails are separate pieces of wood, grooved on their interior faces, that are simply glued to the case sides. There is no joinery connecting the side rails to the legs, though they are supported from below by glue blocks attached to the legs and case sides.

The two medial rails of the case bottom, running from front to back, are attached to the front vertical blocks between the drawers with a pair of wooden pegs, driven diagonally through the bottom of the rails up into the blocks. The medial rails are inserted at an angle, tilting upward toward the central drawer compartment, in order to elevate the central panel of the case bottom. The ends of the pegs are visible from below, though they are somewhat obscured by the brown stain that has been applied to the case bottom. This, as with the pegged connection of the vertical blocks to the upper rail, is quite an unusual construction, though it seems original.

The case bottom’s three oak panels are beveled along their lower edges. Side drawer guides are glued onto the side and medial rails, secured by nails. Kickers, which prevent the drawers from tipping forward when pulled out, are joined above the drawers at either end to the front and rear rails with a single stepped dovetail joint. There are two extra dovetail mortises cut into the top front rail, just outside of the side drawer kickers (fig. 10-11). These would appear to be the result of an error of placement during construction.

Figure 10-11

Figure 10-11The original top of the bureau plat was attached to the case with eight sliding dovetails. This top has been replaced, and the new top is attached with screws, but evidence of the original attachment method remains visible on the top of the case. Along the front and rear rails, sliding dovetail mortises were cut perpendicular to the rails, two per rail (fig. 10-12). These originally held loose double-dovetail blocks,15 half of which protruded up from the top of the rail and locked into recessed sliding dovetail mortises in the top. At some point in the past, these dovetail blocks were cut with a saw to release the top from the case,16 leaving half of each block in the case rails.

Figure 10-12

Figure 10-12In addition to the front and rear dovetail joints, two additional sliding dovetail fixtures were originally employed to secure the top to the case’s side rails. Trapezoidal gaps (~2 1/8 in. high x 1 9/16 in. wide) from these joints are still visible in the case sides. These once contained blocks of oak with dovetails that extended above the side rails (fig. 10-13). Remnants of the original blocks are still present in two of the gaps. The corresponding sliding dovetail mortises in the original top would have had square-sided gaps as well as undercut sections to receive the eight protruding dovetails from the case. The original case top joinery method is similar to that of a preserved bureau plat in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, stamped and dated by Gaspard Feilt around 1750 (object no. 1052:1 to 5-1882) (http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O11865/writing-table-feilt-gaspard/).

Figure 10-13

Figure 10-13The Getty bureau plat’s top is made as a tripartite frame-and-panel construction whose butt-joined pine panels are secured to oak rails. The tabletop is mounted to the rails of the case with eight screws inserted from below. The current top has no mortises corresponding to the original sliding dovetail attachment method seen on the case, confirming that it is a replacement. Further, the panel wood was identified by microscopic anatomy as a species of white pine (Pinus strobus, P. cembra, or P. peuce), none of which is commonly used in eighteenth-century French furniture. These are rabbeted along their upper edges and secured within grooves in the rails.

The drawer sides and bottoms are made from walnut and the fronts are made from oak veneered with tulipwood. The drawer sides are connected to the fronts and sides with four dovetails at each corner. Dovetails are visible at the back, but narrow oak block additions cover the front joints, and the construction of those dovetails is not visible (see fig. 10-7). The tops of the drawer fronts have been veneered with sheets of ebony approximately 5 mm thick. These are most likely later additions. The lower profile of the drawer fronts has been formed by the addition of several curved blocks of oak glued to the bottom of the drawer. The drawers’ bottom boards are secured within rabbets in the side and rear boards; additional narrow strips of wood have been glued to the underside of these joints. The drawer bottoms rest in grooves in the drawer fronts.

The entire carcass is veneered with tulipwood whose grain is mostly diagonally oriented, the exception being the rectangular framed veneer panels on all sides, where it runs horizontally (fig. 10-14). The framed panels on the sides are made from rectangular book-matched patterns, where the two halves reflect each other. On the drawer fronts, the tulipwood veneer appears to have been cut into slightly undersized rectangular pieces and then glued to the substrate. This left some areas on the edges of the drawer fronts (that are covered by gilt bronze mounts) unveneered. These areas were then filled with oak veneer. This peculiar arrangement is almost certainly a restoration (see below). The insides of the legs are veneered with black pearwood, possibly in imitation of ebony or Asian lacquer.

Figure 10-14

Figure 10-14Much of the tulipwood veneer on the bureau plat is in a highly deteriorated condition, including all the veneer on the tabletop and the veneer on the central panels of the drawer fronts, the central panels on the sides, and many apparently replaced sections on the rest of the carcass. The wood in these areas appears rough and almost blistered, with noticeable blotchy darkening around the pores. The likeliest explanation for the deteriorated condition of the wood is that these are all areas where new tulipwood was put in place during a major restoration and that the new wood was chemically treated in an attempt to artificially age it and unify its appearance with the original veneer. Numerous nineteenth-century sources provide instructions to restorers and fakers as to how such chemical aging may be accomplished using a variety of acids and oxidizing compounds.17

Conservators in the Decorative Arts conservation lab attempted to reproduce an aging effect on tulipwood veneer with different acids and found that convincing aging could be achieved with the application of a nitric acid solution, which is commonly mentioned in restoration manuals. On application, the tulipwood lost the strong chromatic contrast between the pinkish- and cream-colored streaks; however, the pores of the wood became noticeably dark, presumably because of preferential absorption of the acid. This darkening of the pores, which might well increase with aging, is very similar to the appearance of the deteriorated tulipwood on the Getty bureau plat. The use of nitric acid would also be in accord with the results of an examination of samples from the deteriorated wood using electron microscopy. Residues of nitric acid would be nearly impossible to detect; however, this analysis found no remnants of other common (detectable) acids or oxidizing agents such as hydrochloric acid, sulfuric acid, potassium permanganate, or potassium dichromate.

Analysis by electron microscopy of a cross-section sample of deteriorated veneer found a thin layer of chrome yellow pigment directly on the surface of the wood. This color is particularly concentrated in the darkened pores of the replacement veneer and appears to have been specifically intended to compensate for the acid-induced deterioration in these areas. Chrome yellow pigment is known to have been first synthesized in the late eighteenth century and only used in painting from the beginning of the nineteenth century. The popularity of the pigment declined after the beginning of the twentieth century as cadmium yellows were introduced and replaced chrome yellow for many purposes.18

In a 1974 letter to Gillian Wilson, J. Sargent of H. J. Hatfield & Sons Ltd. mentions the use of a “certain amount of false colour” in the wood polish during a recent restoration of the bureau plat, saying that without this, the veneer “would have looked rather like a patch work quilt!”19 It must be considered, then, that the chrome yellow could have been applied by Hatfield’s; however, it currently lies below three distinct layers of varnish, and Sargent’s letter specifies that their restorers only added new colored varnish over the existing finish. Thus it seems more likely that the chrome yellow dates to an earlier, nineteenth- or early twentieth-century restoration.

If it is true that the veneer in the framed fields on the drawer fronts and sides of the bureau plat has been replaced as described above, then it would seem likely that these fields were originally decorated in a manner different from that at present. As described in “Commentary” above, other closely related Van Risenburgh examples are decorated with floral marquetry or lacquer panels, and decoration with porcelain plaques could also be possible in this period. Assuming that the Getty bureau plat originally had one of these forms of decoration, there appear to be two plausible explanations for the apparent extensive alteration of the original decoration. If the original decoration was either floral marquetry or lacquer, the surface may have deteriorated to the point where it required replacement; or, if the original panels were porcelain, they could also have been broken or removed from this table and repurposed.

X-radiography of the drawer fronts found no evidence that the substrate had ever been excavated to receive porcelain plaques, nor did it reveal any traces of cutting marks or veneer pins that might suggest the former presence of floral marquetry. Careful examination has also not revealed any direct evidence for the prior presence of lacquer panels on the bureau plat. One piece of circumstantial evidence that lends some support to the idea of original lacquer panels is that the black inner surfaces of the legs are veneered in pearwood. This veneer appears to be original, and the use of smooth-grained domestic wood veneer such as pear was common practice in eighteenth-century Paris for areas that were to be lacquered in imitation of Asian lacquer. It should be noted, however, that the Rothschild example of this model that has lacquer panels (sold, Christie’s 1993) did not, at the time of sale, have black-colored inner surfaces on the legs (see fig. 10-6). The use of ebony veneer on the top and on the edges of the Getty’s drawer fronts may also relate to lacquer panels, but as these are both likely to be later restorations, the connection is tenuous.

There are thirty-six three-dimensional gilt bronze mounts and ten flat frames. Mount patterns can be further divided into groups, in which many of the mount variations are used either twice or four times, the result of copies made from the same master model. Nearly all of the mounts are cast and chased, but the level and precision of the finishing differs within the groups. In addition, the reverse surfaces exhibit a range of patina and texture.

The tabletop’s corner mounts are of particular interest as they appear to be surmoulage copies of preexisting mounts. These mounts have identical impressions of old screw holes on their back sides, which suggests that they were cast from finished mounts (which had been previously attached to a piece of furniture) rather than from master foundry models (fig. 10-15). It is possible, then, that these mounts are copies of the original mounts that were present on the original top, before it was replaced, though this must remain conjecture.

Figure 10-15

Figure 10-15All of the mounts are fixed with slotted head screws directly onto the carcass. In addition, the tabletop edge moldings are fixed to the substrate with slotted head bolts that run through the wood from below and are secured with nuts soldered to the backsides of the mounts (fig. 10-16). The bolt heads are countersunk into the wood. The bolts that attach the perimeter moldings to the top are fabricated in iron with a major diameter of 7/32 in. and 24 threads per inch and appear to be of early industrial production. Their shape, diameter, angle, and thread count are equal to the British standard formalized by Whitworth in 1841. The Whitworth standard was based on contemporary best practice, so it is possible that the bolts were produced before this time. This thread pattern became technically obsolete in the mid-twentieth century.

Figure 10-16

Figure 10-16At least one example of every mount group was analyzed by X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF). The results place the mounts in three general groups. The first group is composed of mounts whose alloy composition is well within the range of known eighteenth-century compositions. This group includes all the mounts on the legs, one of the central mounts on the sides, the flat framing mounts on the drawers and sides, two of the scroll mounts flanking the center drawers, and one of the side drawer escutcheons. The second group includes mounts whose composition is very elevated in zinc (around 26%) and very low in tin, lead, and impurities overall. Based on composition, this group probably dates to the late nineteenth or early twentieth century; it includes one of the side drawer escutcheons, the central mount on the left side, and the center drawer escutcheon on the back of the desk. The locks also probably date to this period. The third group of mounts exhibits a range of compositions intermediate between the first two groups, with levels of impurities that point to a mid-nineteenth-century date. This group includes all of the mounts on the top, as well as two of the side drawer escutcheons and the scrolling mounts flanking the front center drawer. Several of these mounts contain detectable amounts of bismuth, which is extremely rare in French gilt bronze mounts but is quite common in nineteenth-century British castings.

The evidence discussed above suggests two distinct periods of significant restoration prior to the documented restoration by Hatfield’s in 1974. As discussed in “Commentary” above, Shifman argues that the Getty bureau plat was the model for a known copy commissioned by Edward Holmes Baldock in the 1830s (see fig. 10-8).20 The alloy composition of the mounts on the top suggests that the top may have been replaced around this time, perhaps by Baldock, along with several mounts on the lower section. As all the tulipwood veneer on the replaced top has been chemically aged, it seems likely that this veneer dates to the time the top was replaced. And as this veneer matches the condition of the veneer in the fielded panels, it follows that the transformation of the decoration in these panels, and the aging of the tulipwood replacements, may also have occurred under Baldock’s supervision at this time, as suggested in “Commentary” above. The chrome yellow pigment that has been used to mask the darkened pores of the artificially aged veneer would have been available in the 1830s and so might also date to this period.

The X-ray fluorescence results from the gilt bronze mounts also suggest that several mounts and the locks were replaced in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century, and it is also possible that the application of chrome yellow is associated with this restoration. It is not unreasonable to suspect that such a restoration might have occurred around the time of the 1931 Christie’s sale of the bureau plat to the dealer J. M. Botibol in London.

- A.H.,

- Y.C.

- and K.P.

Notes

, 22–23. An edict of Louis XV, registered with Parliament on March 5, 1745, required that all works old or new made with copper, either in pure form or as part of an alloy, be stamped with a crowned C. This mark was canceled on February 4, 1749; therefore, objects with this stamp can be dated to between 1745 and 1749. ↩︎

For more information on Bernard II van Risenburgh, see primarily , 183–99; , 56–63. See also Daniel Alcouffe, in , 323–24. ↩︎

The table appears in a mid-nineteenth-century watercolor of the armory at Lednice, Czechoslovakia. See , 135. See also , 41, fig. 13. ↩︎

See note 1. Correspondence with Reinhold Baumstark, director of the Princely Collections, July 9, 1980, in the files of the Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

Christie’s, Important French Furniture and European Carpets, June 10, 1993 (London: Christie’s, 1993), lot 34. ↩︎

The separate central sections of the pierced corner mounts have at some point been placed upside down. ↩︎

Consequently, the table has never been on display in the Museum’s galleries. ↩︎

, vol. 1, 106–7, no. 28 (Inv. M. 1052). ↩︎

, vol. 1, 106. The desk was long attributed to Antoine-Robert Gaudreaus. It is also attributed to Marteau by Yves Carlier, who refers to the earlier Gaudreaus attribution in , 79, fig. 1. ↩︎

A similar “growing plant” mount was used by Jacques Dubois. See , 150–51, no. 45, for a bureau plat with a similar mount in the form of a small tree set upon a concave base (Inv. OA 6600). ↩︎

, vol. 1, 112–115, no. 30 (Inv. V3528). ↩︎

, vol. 1, 108–11, no. 29 (Inv. V5268). ↩︎

The table appears in a mid-nineteenth-century watercolor; see note 3 above. ↩︎

J. Paul Getty Papers, 1909–89: Art collecting and collections, 1934–74, 1977, 1982, undated: J. M. Botibol 1939–40, in the files of the Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

The single dovetail blocks did not completely fill the mortise cavities, so additional shorter blocks of oak were inserted as gap fillers and to lock the dovetails in place. ↩︎

Saw marks from this operation are visible on the rails in the area surrounding the mortises. ↩︎

See, e.g., , 308, where nitric acid and potassium permanganate are mentioned as chemicals to age the wood. ↩︎

, 100–102. ↩︎

Letter in the files of the Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

, 38–42. ↩︎

Bibliography

- Alcouffe, Dion-Tenenbaum, and Lefébure 1993

- Alcouffe, Daniel, Anne Dion-Tenenbaum, and Amaury Lefébure. Furniture Collections in the Louvre. Vol. 1, Middle Ages, Renaissance, 17th–18th Centuries (Ébénisterie), 19th Century. Dijon: Éditions Faton, 1993.

- Baroli 1957

- Baroli, Jean-Pierre. “Le mystérieux B.V.R.B. enfin identifié.” Connaissance des Arts 61 (March 1957): 56–63.

- Boutemy 1957

- Boutemy, André. “BVRB et la morphologie de son style.” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 49 (May 1957): 165–74.

- Bremer-David et al. 1993

- Bremer-David, Charissa, et al. Decorative Arts: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue of the Collections of the J. Paul Getty Museum. Malibu, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1993.

- Carlier 2009

- Carlier, Yves. “Sur quelques bureaux du duc d’Antin.” In Mélanges offerts à Pierre Arizzoli-Clémentel, edited by Rapahël Masson, 79–85. Versailles: Éditions Artlys, 2009.

- Eudel 1887

- Eudel, Paul. Le truquage: Altérations, fraudes et contrefaçons dévoilées. Paris: Librairie Molière, 1887.

- Getty and Le Vane 1955

- Getty, J. Paul, and Ethel Le Vane. Collector’s Choice: The Chronicle of an Artistic Odyssey through Europe. London: W. H. Allen, 1955.

- Getty 1949

- Getty, J. Paul. Europe in the Eighteenth Century. Chicago: Lakeside Press, 1949.

- Harley 1982

- Harley, R. D. Artists’ Pigments c. 1600–1835: A Study in English Documentary Sources. New York: American Elsevier, 1982.

- Kjellberg 1989

- Kjellberg, Pierre. Le mobilier français du XVIIIe siècle: Dictionnaire des ébénistes et des menuisiers. Paris: Éditions de l’Amateur, 1989.

- Louis XV . . . 1974

- Louis XV, un moment de perfection de l’art français. Exh. cat. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1974.

- Meyer and Arizzoli-Clémentel 2002

- Meyer, Daniel, and Pierre Arizzoli-Clémentel. Versailles: Furniture of the Royal Palace: 17th and 18th Centuries. 2 vols. Dijon: Éditions Faton, 2002.

- Pradère 1989a

- Pradère, Alexandre. French Furniture Makers: The Art of the Ébéniste from Louis XIV to the Revolution. Malibu, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1989.

- Pratt 1991

- Pratt, Michael. The Great Country Houses of Central Europe: Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland. New York: Abbeville Press, 1991.

- Shifman 1984

- Shifman, Barry L. “A Newly Found Table by Edward Holmes Baldock.” Apollo 119, no. 264 (January 1984): 38–42.

- Verlet 1937

- Verlet, Pierre. “A Note on the ‘Poinçon’ of the Crowned ‘C.’” Apollo 151 (July 1937): 22–23.

- Wilson and Hess 2001

- Wilson, Gillian, and Catherine Hess. Summary Catalogue of European Decorative Arts in the J. Paul Getty Museum. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2001.