1. Cabinet

- French (Paris), mid-1730s

- Attributed to Bernard II van Risenburgh (French, after 1696–ca. 1766, master before 1730)

- White oak veneered with bloodwood*, cherry*, ferréol*, and amaranth*; gilt bronze mounts; brass and iron hardware, lock, and keys; brèche d’Alep top

- H: 3 ft. 9 5/8 in., W: 15 ft. 4 1/2 in., D: 1 ft. 9 1/2 in. (115.8 × 468.6 × 54.5 cm)

- 77.DA.91

Description

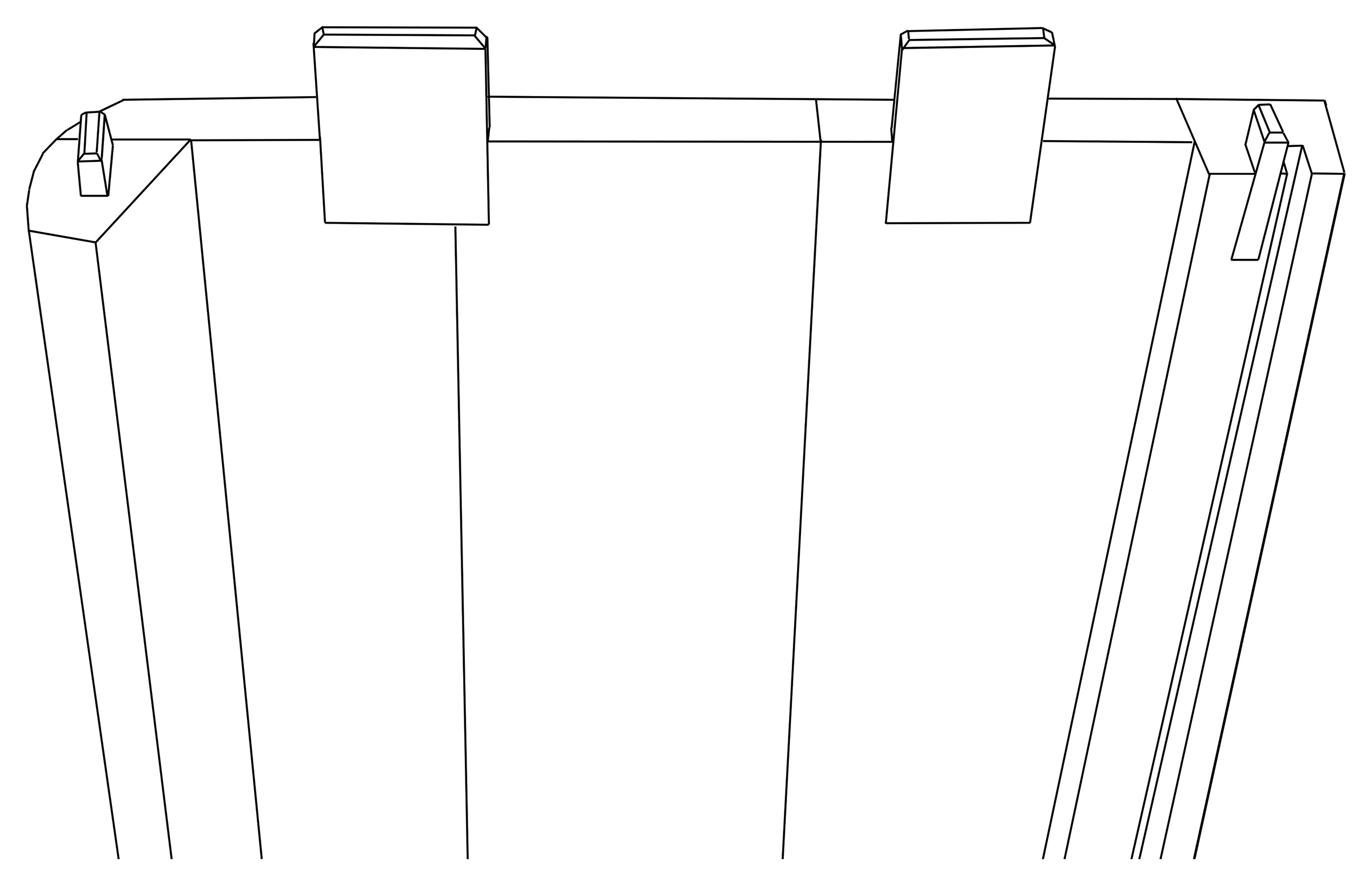

The long cabinet is composed of three similar sections (fig. 1-1) placed side by side and held together with nuts and bolts (see “Technical Description” below). The outer corners of the first and third sections are rounded. Each section is fitted with two doors, with each lower frieze occupied by a long shallow drawer. The outer cabinets have a double-bowed profile, while that of the central cabinet is double bombé. The sides are flat. The top is covered by three slabs of brèche d’Alep, cut to conforming shape. Beneath a shallow frieze, an undulating guilloche molding studded with rosettes and cabochons runs the entire length of the cabinet.

Each of the three sections is similarly mounted (figs. 1-2 and 1-3); a description of one of these will suffice. The upper corners are set with pierced mounts, each consisting of a large cabochon, crested by a spray of leaves and surrounded by a frame of flame work studded with small cabochons. Below hangs a pendant of flower heads enclosed by elongated and interconnected C-scrolls, terminating in a short floral pendant emerging from a corolla. At the base of each corner, just above the plinth and overlapping the broad horizontal molding, is a pierced mount composed of apposed and crossing C-scrolls supporting a leafy bud above, as well as a fan of leaves surrounding a cabochon below, from which depends a leafy bud.

The horizontal molding, cast with short acanthus leaves alternating with honeysuckle on a stippled ground, runs the entire length of the cabinet, continuing around the sides. Each door leaf is framed with a narrow molding cast with leaf tips and buds. At each of the four corners of the frame is an overlapping mount composed of large apposed C-scrolls set at the center over a stippled shield shape that carries a cabochon from which descends a leaf-covered cluster of berries. Above the cabochon is a shell-like form supporting an arrangement of flowers and leaves. The inner surfaces of the apposed C-scrolls are each lined with four smaller C-scrolls, themselves edged with shellwork. A leafy scroll attaches to the ends of the C-scrolls.

The center of the upper frame is covered by a large pierced mount consisting of apposed C-scrolls above with interlocking S-scrolls edged with flame work. The upper part of each C-scroll is set with scrolls of lobed guilloche, and between them is a corolla crowned with leaves and branches of flowers. From the corolla depends a short branch of leaves and flowers.

The edge of the right-hand door is set with a vertical molding composed of framed cabochons on a stippled ground. The molding terminates below in a small cup of two leaves and is capped above by a small mount consisting of two short curled leaves and two cabochons. Each door carries a shield-shaped keyhole escutcheon, outlined with C-scrolls. The central cabochon, pierced with a keyhole, is surrounded by shellwork that extends into a spiral below. Each of the three lower drawers also carries a central keyhole escutcheon composed of C-scrolls surrounding shellwork, extending to either side and carrying scallop shells and terminating in small clusters of leaves. To either side of the escutcheon are pull handles, each set on a plate of radiating lobes. The surface of the knob is set with an eight-petaled rosette.

The two doors of the central section (see fig. 1-2) of the cabinet are veneered with panels of asymmetrical marquetry composed of amaranth scrolls enclosing a field of trellis formed by amaranth crossings. The squares of the trellis are filled with triangles of bloodwood, the grain arranged to form squares. The whole asymmetrical arrangement is set over a diamond of ferréol. The panel is framed by a broad band of amaranth, which forms a background to the large pierced central mount and the four corner mounts. The door panels of the side sections (see fig. 1-3) of the cabinet are decorated with amaranth C- and hipped S-scrolls surrounding a ferréol trellis framed similarly to those areas on the doors of the central section but with crossings here of bloodwood. The panel is surrounded by a triple frame of amaranth. At the center top the frame develops into a large apron, both backing and triple framing the central mounts. The remaining area of the panel is veneered with bloodwood, with the grain arranged vertically.

The outer frame of each door is double framed with amaranth, with bloodwood between. The frieze below the stone top is plainly veneered with amaranth. The same wood frames the fronts of the drawers, surrounding a field of ferréol cut to form chevrons. Small vertical strips of wood, set between the central and the outer sections, are veneered with ferréol. The sides of the cabinet (fig. 1-4) are veneered with a pomegranate-shaped central motif formed by C-scrolls of amaranth surrounding a diamond of ferréol and bloodwood. The panel is framed by a double border of amaranth centered by one of bloodwood. The field of the panel is veneered with ferréol featuring a strongly marked nonparallel waving grain in various tones of brown. The interiors of the doors are veneered with cherry, with a frame of amaranth. The iron lock mechanism, fitted to the side of the right-hand doors of the three sections, activates a double-pronged lock and upper and lower long bolts.

Marks

Inscribed “DAVAL” twice in chalk (?) on the back of the right cabinet (77.DA.91.f) (fig. 1-5). Also on the right cabinet is a paper label glued to the top of the carcass, beneath the marble slab. It is inscribed in ink, “les Clefs pour la bibliothèque.”

Figure 1-5

Figure 1-5Commentary

The cabinet is attributed to Bernard II van Risenburgh on the basis of the style of the gilt bronze mounts and the appearance of four mounts of the same model on various pieces of ébénisterie stamped with his initials or firmly attributed to him.1 The six pierced upper mounts bearing large cabochons appear in the same form on the upper corners and back of a cabinet set with ten drawers, with fronts veneered with Japanese lacquer that was probably made early in Van Risenburgh’s career, between about 1730 and 1735.2 Mounts of this model are also found set at the upper backs of more pronouncedly rococo pieces: a pair of commodes delivered to the Residenz in Munich between 1730 and 1732, displayed in the Kurfürstenzimmer, or Electoral Rooms,3 and another commode with front corner mounts of the same massive model in a private collection, formerly belonging to Baron A. von Goldschmidt-Rothschild.4 Ronfort, Augarde, and Langer have dated these commodes to the mid-1730s, the likely date of the Museum’s cabinet. The mounts also appear on a pair of corner cupboards dating from the 1750s in the Walters Art Museum.5

The gilt bronze mounts set at the corners of the six frames across the front are a larger and more elaborate form of the “cruciform” mounts found on later commodes by Van Risenburgh (see cat. nos. 5 and 6). They have been found on only one other object that can be attributed to him, a corner cupboard mounted with a shaped and framed panel of Japanese lacquer with two doors that was illustrated in Connaissance des Arts in 1962.6 The mounts centering the upper frames are not found on any other known pieces by him. The pierced mounts on the lower corners above the plinth are found in a similar position on the pair of display cabinets in the Museum (cat. no. 2), also stamped with the maker’s initials. A molding set with anthemia of the same model as that edging the upper profile of the plinth is also found, in a similar position, on a cupboard for folio volumes and an armoire (fig. 1-6) veneered with panels of Chinese red lacquer, both made for Jean-Baptiste de Machault d’Arnouville around 1755.7

Figure 1-6

Figure 1-6All other aspects of this cabinet are unique in Van Risenburgh’s oeuvre. Its size allows it to stand almost alone in the whole field of eighteenth-century Parisian ébénisterie. It is only surpassed in length by a bibliothèque set with panels of première and contre-partie panels of brass and tortoiseshell marquetry in the Wallace Collection.8 That cabinet measures 602 centimeters in length and was made by Étienne Levasseur in about 1775.

The marquetry is also of an almost unique design and must represent an early stage in Van Risenburgh’s career, before his more characteristic bois de bout floral marquetry evolved. Trelliswork enclosed in a broad undulating band of amaranth is found on the door of an apparently unstamped corner cupboard that was sold in New York in 1941.9 Although the vertical profile of the cabinet is straight and the front only slightly bombé, an early example of a rather extreme form of rococo appears on the asymmetrically decorated door panels of the central section.

The intended use of this cabinet is not clear. A paper label is glued to the top, beneath one of the marble slabs. It is inscribed in ink, “les Clefs pour la bibliothèque.” The interior shelves can be adjusted to a variety of heights, suggesting that the cabinet may have been used for storing books, in addition to drawings, prints, maps, or plans, rolled or flat.

As yet the cabinet has not been found in any eighteenth-century inventory or sale. It is inscribed “DAVAL” on the back in large cursive script (fig. 1-5). Nicolas Daval was a marchand-mercier working in Paris from the 1780s until his retirement in 1821. He had two shops, one at 15, quai Malaquais and the other at 1, rue des Petits Augustins. At his retirement his remaining stock was sold in three sales, on December 26–29, 1821; January 28–February 2, 1822; and March 18, 1822. Daval died in 1838. A fourth sale was held on December 5–7, 1838, after his death.10

The cabinet is not found in the catalogues of those sales and must have passed through his hands at some earlier date. By 1877 it belonged to comte Henri Greffulhe.11 It stood in the former hôtel de Mouchy, located at 8–10, rue d’Astorg. Greffulhe’s uncle was the comte Louis d’Armaillé, a friend and adviser of Richard Wallace.12 Greffulhe’s wife, Élisabeth de Riquet de Caraman-Chimay (1860–1952), was the muse of Marcel Proust and led an art salon of great style.

Provenance

Before 1838: Nicolas Daval, French, died 1838 (Paris, France); before 1877–1932: Comte Henri Greffulhe, French, 1848–1932 (8, rue d’Astorg, Paris, France), by inheritance to his wife, Élisabeth de Riquet de Caraman-Chimay, 1932;13 1932–37: Élisabeth de Riquet de Caraman-Chimay, Comtesse Greffulhe, French, 1860–1952 (Paris, France), sold, A Selected Portion of the Renowned Collection Formed by the Comte Greffulhe and Sold by Order of the Comtesse Greffulhe [ . . . ], Sotheby’s, London, July 23, 1937, lot 50, to both Arnold Seligmann and Trevor and Co. for £1,400; 1937– : Arnold Seligmann & Cie, 1912–46; 1937– : and Trevor and Co.;14 1950s: David Drey (London, England), sold to Maurice Aveline; 1950s: Maurice Aveline, French (Paris, France), sold to Antenor Patiño; ca. 1957: Antenor Patiño, Bolivian, 1896–1982 (Paris, France), sold to Aveline & Co.; 1977: Aveline & Co. (Paris, France; Geneva, Switzerland), sold to the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1977.

Exhibition History

Getty loan to the Art Institute of Chicago (Chicago), November 23, 1977–August 15, 1978.

Bibliography

, 466; , vol. 2, 426; , 37, 39–40, no. 3; , 184–85, fig. 168; , vol. 2, 377, ill.; , 18, no. 11; , 45, fig. 20; , 8, no. 11; , 61 n. 16; , 59 n. 3.

- G.W.

Technical Description

The cabinet is constructed as three separate cases that are structurally identical. The cases are fabricated from white oak of middling quality with numerous knots and, in some places, narrow bands of light-colored sapwood that have not been trimmed off. The oak is primarily flat sawn into relatively narrow boards, mostly 13 cm or less, that are glued together on edge to form larger panels.

Each wooden case is assembled from seven independently constructed sections: a frame-and-panel top, two side panels in plank construction, a frame-and-panel back, two plank-constructed doors with breadboard ends, and a lower drawer case. The frame-and-panel tops are each made with three equally sized raised panels. The side-to-side rails extend to the ends of the tops, and the four short front-to-back rails are fixed between with double-pinned, haunched mortise-and-tenon joints. The pairs of pins are offset so that one pin is noticeably farther from the joint line than the other (fig. 1-7); this is true for all pinned joints in the cabinet. It also appears that the pins (and/or the drill used to cut their holes) are tapered. On one side of the 2.3-cm-thick frames, the pins measure on average just over 7 mm, while on the other side the average measurement is closer to 9 mm. The grooves for the panels extend to the ends of the long rails and are visible on the sides of each case when the upper gilt bronze moldings are removed. The three raised panels of each top section are made of between 3 and 7 pieces of varying width, butt joined together with the grain running from front to back. On the middle case, the beveled edges of the panels face downward; on the left and right cases, the bevels face up. Around the perimeter of each frame-and-panel assembly, five 3.0-cm-thick pieces of oak are glued down to the top surface with no joinery between the elements (fig. 1-8); seen from the front, these elements form the narrow veneered frieze just below the marble tops.

Figure 1-7

Figure 1-7 Figure 1-8

Figure 1-8The case sides are each made of four planks about 2.3 cm thick, butt joined with the grain oriented vertically. At the front edges, additional blocks of wood have been glued to the inner face, forming pseudo-stiles. At the rear edges, the last piece of wood glued to each side panel is of double thickness, forming a stile at the rear. Each side is attached to its corresponding top and lower drawer case with a set of four loose tenons at each end, two larger tenons in the main panel and smaller tenons in the front and rear stiles (fig. 1-9). The side and rear loose tenons are placed in mortises that are open to the interior of the case.

Figure 1-9

Figure 1-9Each of the three case backs is assembled in frame-and-panel construction with four narrow, vertically oriented panels (see figs. 1-1 and 1-5). Although the panels are only about 40 cm wide, most are fabricated from four narrow boards, glued on edge without joinery. The edges of the panels are beveled along the edges on the rear sides; the sides of the panels facing the interior of the cabinet are flat across their entire surface. As on the tops, the stiles and rails are secured with double-pinned mortise-and-tenon joints with offset tapered pins. The back frame-and-panel assemblies are rabbeted along the rear edges of all four sides, forming tongues that fit into corresponding grooves in the tops, sides, and base sections.

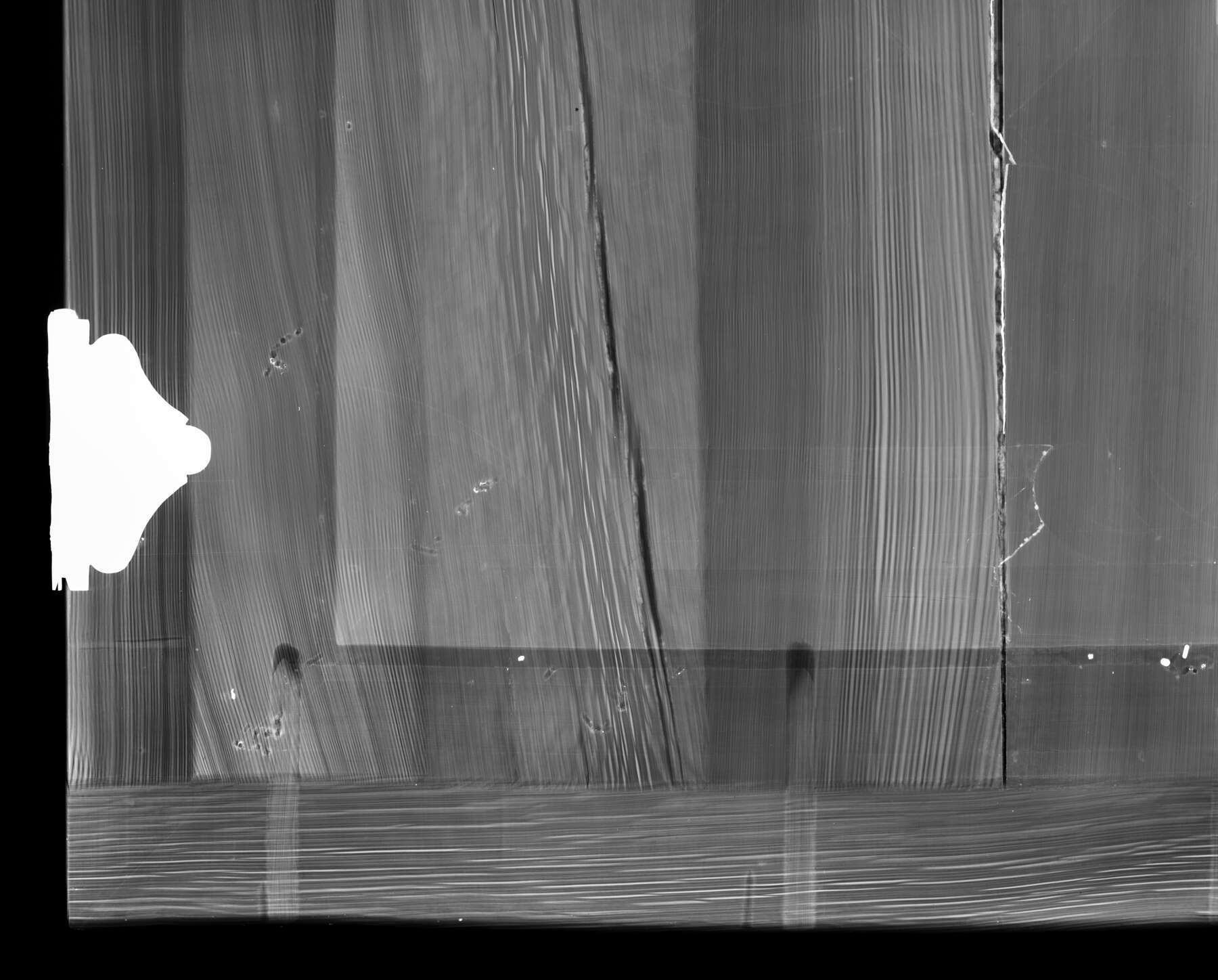

The doors (fig. 1-10) are each constructed of eight vertical oak boards, butt joined together and capped at the top and bottom with thin horizontal battens. Each batten is fixed to the door panel with five long pegs, equally spaced along the length of the door, that pass through the battens and into the composite door panel. X-radiography shows that the holes for the pegs have been drilled with a round-tipped spoon bit, as was customary in the eighteenth century (fig. 1-11). The central fields of the door fronts are slightly raised in comparison to the areas outside the gilt bronze frames. The X-radiographs also show that this raising has been accomplished by planing down the perimeter of the doors rather than adding wood to the center field.

Figure 1-11

Figure 1-11The lower drawer cases, or base sections, are constructed as structurally separate units. Each base section comprises a frame-and-panel top with the rest of the case below in plank construction. The frame-and-panel tops are constructed identically to the tops of the cabinets, with the exception that the panels are rabbeted on their upper edges, making them flush with the framing members on the upper surface. The sides and backs of each base section are made of thick, single boards of oak, joined at the rear corners with double, through dovetails. Below the drawers, spanning the front of the base sections, are single boards that are attached at each end to the base sides with a single, blind dovetail. These joints are reinforced with wooden pins, driven through the dovetails into the side boards (fig. 1-12). The front corners of the bases are made thicker with short blocks of oak glued to the inner faces of the case sides. Additional pairs of wooden pegs, driven from below, further secure these blocks to the transverse board below. Short horizontal boards of oak, running from front to back at the side of each case, serve as drawer runners. These are glued to the sides of the base and secured to the back boards with pairs of through dovetails, reinforced with wooden pegs. Narrow oak drawer guides are glued to the upper surface of the drawer runners, and heavy corner blocks are glued into the corners between the base sides and the base tops to provide a secure connection between the two elements.

Figure 1-12

Figure 1-12The drawers (figs. 1-13 and 1-14) are constructed of oak, with through dovetails at the rear and half-blind dovetails (covered by thin wooden blocks) at the front. The drawer bottoms are each made of four boards, butt joined, with the grain running from side to side. The bottoms are nailed into rabbets along the sides and backs of the drawers. Along the front edges, however, the drawer bottoms fully overlap the drawer fronts and are attached with glue and nails. The drawer fronts are made of two thicknesses of vertical oak board, laminated as necessary to build up the thickness necessary for their bowed forms.

This cabinet makes unusually extensive use of highly figured ferréol veneer. Ferréol is the modern French name for a thus far unidentified species of the genus Swartzia that has been linked by Viaux-Lauquin to the wood called “fereol” by Roubo.15 The identification of the veneer used on this cabinet as Swartzia sp. was made by detailed microanatomical study of thin sections from a sample taken from the bottom edge of a drawer.16 Further examination of anatomical features on the side panels was conducted without sampling, using a high magnification digital microscope; this confirmed that the side panels are almost certainly the same wood.17 Roubo describes ferréol as follows:

Fereol. Ce bois croît à Cayenne, & porte le nom de celui qui l’a découvert; il se nomme aussi bois marbré: le fond de ce bois est blanc, & veiné ou tacheté de rouge. Il y a au Cabinet d’Histoire Naturelle du Jardin du Roi, du bois de fereol dont le grain est très-fin, & dont le fond est de couleur jaune foncé, avec des raies étroites de couleur brune, tirant fur le violet; c’est peut-être une nuance dans l’espece : au reste, ce bois est beau, & se travaille très-bien.18

(Ferréol. This wood grows in Cayenne [present-day French Guiana] and bears the name of he who discovered it; it is also called marbled wood: the ground of this wood is white, veined, or mottled with red. There is at the Office of Natural History of the King’s Garden, ferréol wood, whose grain is very fine and whose ground is dark yellow in color, with narrow streaks of brown color, tending toward violet; perhaps this is a variety of the species: for the rest, this wood is beautiful, and works very well.)

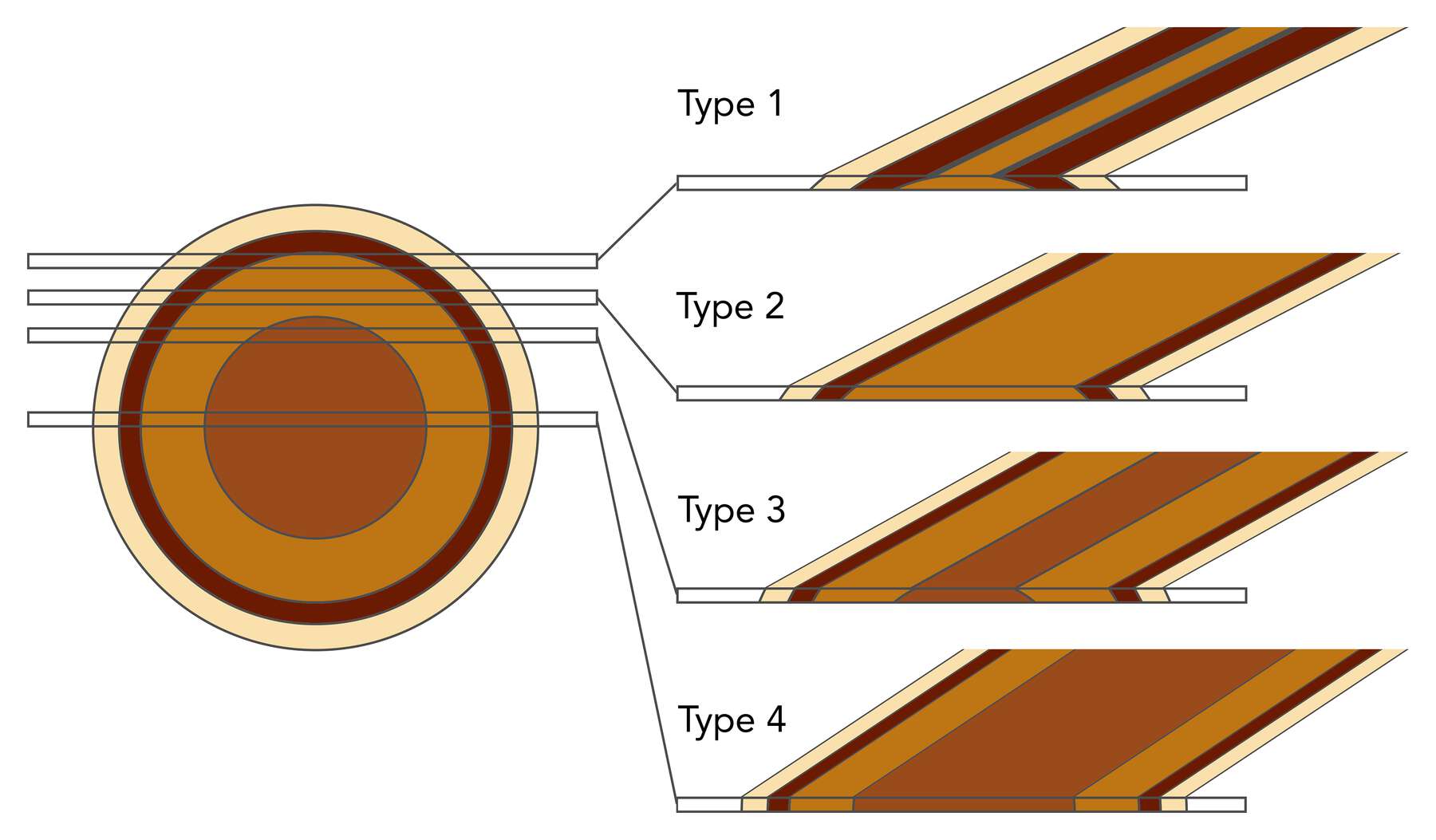

The varied and diverse figure of ferréol noted by Roubo accords well with the veneer used here by Van Risenburgh. The log from which this veneer was cut appears to have had at least four distinct concentric zones of color and to have been flat sawn (fig. 1-15). By carefully selecting different sheets from the packet of veneer made from this log, the ébéniste was able to create a remarkable range of different patterns and compositions (fig. 1-16). The outermost band of the log was the sapwood, which is nearly white. Normally, sapwood is not used in ornamental veneers, but here Van Risenburgh uses it to create the distinctive bright stripes, particularly evident on the doors and drawer of the central cabinet section. These areas of striped diamonds and chevrons are composed using sheets of veneer corresponding to type 3. Just inside the sapwood of this log lay a variegated and irregular band of quite dark, brown wood. This stripe is prominently displayed in the background fields of the sides, where four vertical bands of type 2 veneer sheets are joined, following the curvature of the grain, to form the design. The upper and lower sections of the background are book-matched, and small “arrowheads” of sapwood are carefully retained on the centerline, just above and below the cartouche border.

Figure 1-15

Figure 1-15 Figure 1-16

Figure 1-16Inside the dark band lay a rather wide light brown band that forms the majority of the background field on the sides. This band is also used extensively in the checkerboard pattern at the center of the side doors, relying primarily on type 2 veneer. At the center of the ferréol log used here lay a reddish-brown core. This rich tone is featured most prominently inside the cartouches of the cabinet sides where the diamond-matched pattern features broad, curving bands, drawn from type 4 veneer sheets.

During the original construction of the marquetry decoration of these cabinets, the individual elements were glued directly on the finished carcass, one piece after the other. Small iron nails were placed alongside some pieces of veneer to prevent them from sliding out of position during gluing and clamping. These veneer pins were removed once the glue had dried, and the next abutting piece of veneer was then glued in position. X-radiography revealed several small holes that had been caused by the placement of these veneer pins, which are now only visible in X-ray. The veneer pin holes on this cabinet are smaller and less frequent than those found on other, similar works of ébénisterie by Van Risenburgh, such as the display cabinets (cat. no. 2). Close examination of the surface under magnification reveals no shoulder knife marks or any distorted wood fibers around the tight curves of the veneer pieces. This implies that the veneer elements were mostly cut to size before being glued in their final position.

The gilt bronze mounts appear to be almost entirely original to the cabinet. Fourteen representative mounts, including at least one of each model, were analyzed by X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy to determine the composition of their base alloy. In addition, two measurements were made of the soldering alloy used to join separately cast elements into longer runs of molding. The mounts, with one exception, were found to have compositions common in eighteenth-century Parisian casting brass, with zinc levels between 17 and 23%, tin between 0.35 and 0.75%, and lead between 0.75 and 1.5%. Furthermore, levels of impurities in the metal, such as iron, arsenic, silver, nickel, and antimony, were found to be in the normal range for mounts of the period. The mount found to be different from the others was a drawer handle backplate (second from the right) that was a copy, made in Paris in 1998 to replace a missing backplate. As is common in late twentieth-century Parisian castings, the levels of tin and iron in this backplate are significantly lower than the normal range for the eighteenth century, and impurities such as silver, arsenic, and antimony are virtually absent. The composition of the soldering metal is very much like that of the casting metal, with the exception that the zinc level is elevated to between 31 and 34%, lowering the melting point considerably and thus facilitating the soldering process.19

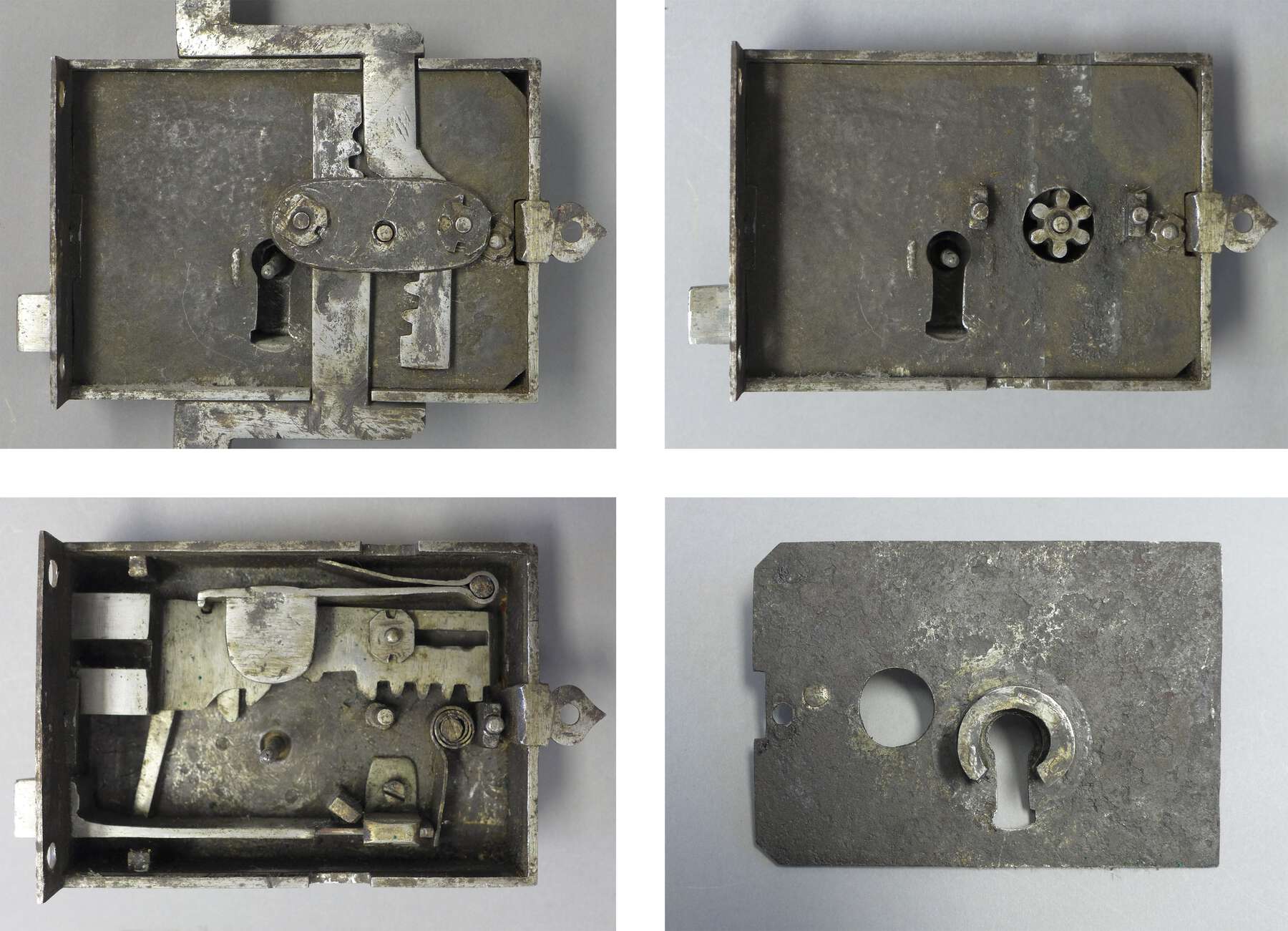

The iron locks on the right-hand door of each cabinet section are particularly noteworthy. They are finely made, double-throw locks, with double bolts engaging the corresponding door to the left (a spring catch allowing the doors to be closed and latched without the key) and, in addition, long bolts running both up and down that engage the case top and bottom. All four bolts are operated by the turn of a single key, using a two-layered mechanism (fig. 1-17). The upper and lower bolts are held in place by decorative iron guides.

Figure 1-17

Figure 1-17The cabinet sections are held together by iron nuts and bolts, two through the upper framing of the tops and two through the sides of the bottom sections. Half of the bolts are now missing, and of the remaining four, none appears to be original.

The three marble tops are made of brèche d’Alep and are about 2.5 cm thick. Brèche d’Alep is a heterogeneous calcareous stone consisting of multicolored rounded cobbles in a sand and gravel matrix that ranges in tone from beige to orange. The dominant colors of the larger cobbles are tan and cream, though numerous red, brown, and even black cobbles are found as well. Many similar limestone breccias of this type occur in varying colors throughout the Mediterranean. The stone is named for a variety sourced near Aleppo in modern Syria. The stone used on these cabinets, however, is thought to have been quarried in Le Tholonet, Bouches-du-Rhône, France. Although the quarry is inactive now, it had been in use since ancient times.

Although there is no corresponding documentation, the color and the quality of the varnish suggests that the cabinets have been refinished recently, probably shortly before their acquisition by the Museum. No evidence could be found of the original surface preparation.

- A.H.,

- Y.C.

- and R.S.

Notes

For more information on Bernard II van Risenburgh, see primarily , 183–99; , 56–63. See also Daniel Alcouffe, in , 323–24. ↩︎

See , 35, fig. 2. Formerly with Bernard B. Steinitz. ↩︎

A pair: Inv. Res. Mü. M 1037, 1038. In the collection of the Bayerische Verwaltung der staatlichen Schlösser, Gärten und Seen, and on display at the Residenz München in the Kurfürstenzimmer. , 41, fig. 9. See . The commodes are unstamped. ↩︎

See , 44, fig. 19. ↩︎

Acc. no. 65.63–64. , 3, fig. 1. This pair of encoignures bears the stamp of Martin Étienne Lhermite, Van Risenburgh’s son-in-law. ↩︎

, 42–49, fig. 6. Then in the possession of a private Parisian collection; its present whereabouts are unknown. ↩︎

For the armoire, now at Versailles, see , vol. 2, 50–52, no. 8; , 156–57, no. 41 (T. Wolvesperges); , 55 (acc. nos. V5090 and OA 9599). For the folio cupboard, now in a private collection, see , 154–55, no. 40 (A. Pradère). ↩︎

, vol. 2, 546–52, no. 120 (acc. no. F390). ↩︎

Parke-Bernet Galleries, English and French XVIII Century Furniture, Parke-Bernet Galleries, May 28–29, 1941 (New York: Parke-Bernet Galleries, 1941), lot 432. ↩︎

, 60–61, esp. n. 16; M. Bonnefonds de la Vialle, commissaire-priseur, Catalogue d’une collection d’objets d’art et de haute curiosité, December 5–7, 1838 (Paris: M. Bonnefonds de la Vialle, 1838). The fourth sale following Daval’s death was held at his home at 80, rue du Faubourg Saint-Denis, Paris. ↩︎

, 466. ↩︎

See preface to Sotheby’s, A Selected Portion of the Renowned Collection Formed by the Comte Greffulhe and Sold by Order of the Comtesse Greffulhe and of the Duc and Duchesse de Gramont, Sotheby’s, July 23, 1937 (London: Sotheby’s, 1937). ↩︎

Cabinet mentioned in , 466. ↩︎

Handwritten note in a copy of the auction catalogue in the collection of the Getty Research Institute library. ↩︎

. ↩︎

See “Wood identification report, 77.DA.91 Sample number 1,” by Arlen Heginbotham, in the files of the Decorative Arts and Sculpture Conservation Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

See “Wood identification report, 77.DA.91 Sample numbers 2–3,” by Arlen Heginbotham, in the files of the Decorative Arts and Sculpture Conservation Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

, 776. ↩︎

For a discussion of the composition and nature of soldering metal, see , 150–65. ↩︎

Bibliography

- 18th Century: Birth of Design 2014

- 18th Century: Birth of Design: Furniture Masterpieces 1650–1790. Exh. cat. Paris: Éditions Faton, 2014.

- Baroli 1957

- Baroli, Jean-Pierre. “Le mystérieux B.V.R.B. enfin identifié.” Connaissance des Arts 61 (March 1957): 56–63.

- Bremer-David et al. 1993

- Bremer-David, Charissa, et al. Decorative Arts: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue of the Collections of the J. Paul Getty Museum. Malibu, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1993.

- Cator and Pradère 2009

- Cator, Charles, and Alexandre Pradère. “A Connoisseur’s Eye: George Byng Boulle Furniture.” Apollo 169, no. 566 (June 2009): 56–64.

- Gruber 1992

- Gruber, Alain, ed. L’art décoratif en Europe. Vol. 2, Classique et baroque. Paris: Citadelles & Mazenod, 1992.

- Guellette 1877

- Guellette, Charles. “Les cabinets d’amateurs à Paris: La collection de M. H. de Greffulhe, II: Ameublement.” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 15 (1877): 462–74.

- Heginbotham 2013

- Heginbotham, Arlen. “Bronzes Dorés: A Technical Approach to Examination and Authentication of French Gilt Bronze.” In French Bronze Sculpture: Materials and Techniques 16th–18th Century, edited by David Bourgarit, Jane Bassett, Francesca Bewer, Geneviève Bresc-Bautier, Philippe Malgouyres, and Guilhem Scherf, 150–65. London: Archetype, 2013.

- Hughes 1996

- Hughes, Peter. The Wallace Collection Catalogue of Furniture. 2 vols. London: Trustees of the Wallace Collection: 1996.

- Jullian 1962

- Jullian, Philippe. “Comment identifier le vernis Martin.” Connaissance des Arts 119 (January 1962): 42–49.

- Langer 1997

- Langer, Brigitte. “Zwei Kommoden des Bernard II van Risenburgh.” Patrimonia 134 (1997): 7–39.

- Louis XV . . . 1974

- Louis XV, un moment de perfection de l’art français. Exh. cat. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1974.

- Meyer and Arizzoli-Clémentel 2002

- Meyer, Daniel, and Pierre Arizzoli-Clémentel. Versailles: Furniture of the Royal Palace: 17th and 18th Centuries. 2 vols. Dijon: Éditions Faton, 2002.

- Pradère 1989a

- Pradère, Alexandre. French Furniture Makers: The Art of the Ébéniste from Louis XIV to the Revolution. Malibu, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1989.

- Pradère 2014

- Pradère, Alexandre. “Lerouge, Le Brun, Bonnemaison: Le rôle des marchands de tableaux dans le commerce du mobilier Boulle, de la Révolution à la Restauration.” Revue de l’Art 184, no. 2 (June 2014): 47–62.

- Pruchnicki 2013

- Pruchnicki, Vincent. Arnouville: Le château des Machault au XVIIIe siècle. Paris: Éditions Lelivredart, 2013.

- Randall 1970

- Randall, Richard H., Jr. “A French Quartet.” Walters Art Gallery Bulletin 23, no. 3 (December 1970): 1–4.

- Reitlinger 1963

- Reitlinger, Gerald. The Economics of Taste. Vol. 2, The Rise and Fall of Objets d’Art Prices since 1750. New York: Barrie and Rockliff, 1963.

- Ronfort, Augarde, and Langer 1995

- Ronfort, Jean Nérée, Jean-Dominique Augarde, and Brigitte Langer. “Nouveaux aspects de la vie et de l’oeuvre de Bernard (II) van Risenburgh (c. 1700–1766).” L’Estampille/L’Objet d’Art 290 (April 1995): 29–52.

- Roubo 1774

- Roubo, André Jacob. L’art du menuisier ébéniste. Paris: L. F. Delatour, 1774.

- Viaux-Lauquin 1997

- Viaux-Lauquin, Jacqueline. Les bois d’ébénisterie dans le mobilier français. Paris: Léonce Laget, 1997.

- Wilson and Hess 2001

- Wilson, Gillian, and Catherine Hess. Summary Catalogue of European Decorative Arts in the J. Paul Getty Museum. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2001.

- Wilson 1978–79

- Wilson, Gillian. “Acquisitions Made by the Department of Decorative Arts, 1977 to Mid 1979.” J. Paul Getty Museum Journal 6–7 (1978–79): 37–52.